- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Marxist Analyses and Social Anthropology

About this book

Reflecting the first evaluation among British and American anthropologists of the relevance of Marxist theory for their discipline, the studies in this volume cover a wide geographical and social spectrum ranging from rural Indonesia, Imperial China, Highland Burma and the Abron kingdom of Gyaman.A critical survey assesses the value of some key ideas of Marx and Engels to social anthropology and places in historical perspective the changing attitudes of social anthropologists to the Marxist tradition.Originally published in 1975.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Marxist Analyses and Social Anthropology by Maurice Bloch in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

EMPIRICISM AND HISTORICAL MATERIALISM

Modes of Production, Kinship, and Demographic Structures

Translated by Kate Young and Felicity Edholm

This chapter1 is intended to present with as much clarity and brevity as possible some theoretical considerations of the problem on the relationship between mode of production, kinship relations, family organization, and demographic structures. The aim is above all methodological, and its basic source is the recent work of Aram Yengoyan (1968a, b; 1970; 1972a, b) concerning the section and subsection systems of the Australian Aborigines. A complete analysis of these societies is not attempted here, still less a comparison, statistical or otherwise, of the various forms of economic and social organization found among hunting and gathering peoples about which we have valid information. What is attempted is a contribution to the study of the problem of the ‘structural causality’ of the economy: the effect of relations of production at a given level of development of the productive forces, that is to say the mode of production, on other levels of social organization (see Godelier 1973: foreword and Ch. 1).

Two preliminary points should be made. The family is not, contrary to what some demographers and sociologists still think, the basic unit, or the cell of society, nor is it, as the evolutionary anthropologist Julian Steward (1951) argues,2 the first step in the evolution of human society, nor even the first ‘level of integration’ of society. A family cannot exist and reproduce itself through the generations independently of other families (Lévi-Strauss 1960: 278). This interdependence is imposed, in the first place, by the universal existence of the incest prohibition and the rule of exogamy which accompanies it, whatever its forms or the range of its application may be. The internal structure of a family presupposes from the first the existence of social rules regulating forms of marriage, filiation, and residence, which are required for the legitimate existence of any family and which determine some aspects of the ‘developmental cycle’ (Goody 1972: 22, 28; Fortes 1958). These social rules, together with the terms which describe relations of consanguinity, alliance, etc., make up the tangible aspect of what, in an empirical and unrigorous fashion, is called kinship.

In order, however, to explain why, within a given society, a type of family organization functions as part of the organization of production and/or consumption, or why it does not function in this way, or why it does so only partially, we must go beyond these tangible aspects of kin-ship relationships and also examine the social conditions of production, the material means of social existence. It is these social conditions which determine the role of the domestic group in the social process of produc-tion, the presence or absence of a social division of labour existing beyond the limits of the domestic group and of local communities (see Kula 1972). It is these social conditions which also determine the presence or absence of slaves or other types of dependants within the domestic groups. These aspects of the function of family groups depend on the nature of the social relations of production. In other words, the internal structure of the type of family ‘appears’ to depend on at least two sets of prerequisite social conditions: kinship relations and relations of production. This is never more than an empirical and provisional formulation which will be untenable or will at least present insoluble problems when we come to analyse societies in which kinship relations take on directly, from within, the function of relations of production. In this case it is difficult to contrast economy and kinship as though they were two ‘institutions’ with different functions. One can already see here some of the dangerous assumptions of the empiricist method. On the one hand, institutions are defined by their apparent functions, and, on the other, it is presumed that distinct institutions are necessary to carry out distinct functions. The epistemological consequences of such assumptions are critical because, as we shall see in greater detail, they preclude the construction of a rigorous theory of ‘structural causality’ of the infrastructure.

Our second preliminary point is concerned with demographic structures. These structures are not aprimum movens but rather the combined result of the action of several ‘deeper’ structural levels, of a hierarchy of causes, the most important of which is again the mode of production; that is to say the productive forces and the nature of the social relations of production which make up the infrastructure of the society. Having noted this, the significance of the fact that demography is the ‘synthetic’ result of the action of several structural levels, of a combination of causes of varying importance, must be analysed further. It means (and it is in this that the complexity of the analysis of the demographic structures lies) that every type of social relations, each structural level, is subject to the functioning and reproduction over time of specific demographic conditions. The population of a society is the synthetic result of the combined action of these specific demographic constraints which affect it differently at each level.3 The combined effect of these constraints is that every demographic structure has a causal effect on the functioning and the evolution of societies. The work of Aram Yengoyan on the demographic conditions necessary for the working of the Australian kinship systems serves as an example which shows how demography is, at one and the same time, cause and effect; i.e. the condition of the functioning and of the reproduction through time of economic and social structures. By way of example we may take the case of the Kamilaroi of New South Wales as described by Elkin (1967: 162).4 They have a section system and each section has a different name.

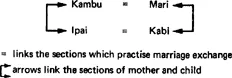

Diagram of the Kamilaroi Marriage System

This diagram tells us that a man from Kambu section will marry a woman from Mari section and that their children will be Kabi. A Kabi man will marry an Ipai woman and their child will be Kambu. If the wife of a Mari man is Kambu, their child is Ipai, and this child then marries a Kabi woman and their child will be Mari. It will be seen that all Kamilaroi belong to a number of kinship categories. If I am Kambu, my wife is Mari, my son is Kabi; his wife is Ipai and my grandson belongs to my section. Equally, since I am Kambu, my mother is Ipai and my father Kabi; my mother's brother, like my mother, is Ipai and his children are Mari since he married a Kabi. My father's sister is Kabi and her children are also Mari. In the Mari section are all my patrilateral and matrilateral cross-cousins and this is the section to which my potential wives belong.

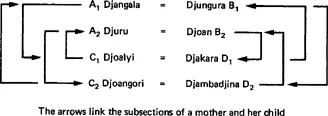

The same principles that apply to section systems also apply to sub-section systems but in their case Ego's kinsmen are divided into8 groups instead of 4. This produces a division between the category cross-cousins and their children. Marriage with a first-degree cross-cousin is prohibited but it is prescribed with a second-degree cross-cousin, i.e. MMBD or FFZSD. The diagram below, following Elkin (1967: 168), shows the working of a subsection system of a tribe from East Kimberley.

Diagram of a Subsection System in East Kimberley

If I am A1, my cross-cousin is B2 but the daughter of the cross-cousin of my mother belongs to B1, that is the subsection into which I can marry, etc. Here we have the characteristics of the so-called Aranda system which were extensively analysed by Claude Lévi-Strauss in The Elementary Structures of Kinship. Aram Yengoyan tried to determine mathematically what the total population of a tribe which is divided into 10 local groups (hordes or bands), each occupying a defined territory, has to be to enable a kinship system of subsections to function so that all men of 25, the marriageable age, can find a wife of about 15 or more within the subsection prescribed for him. Each man should have a choice of about 25 women who satisfy these conditions. Yengoyan (1968a: 194–8) shows that the total population has to be 1,070 indi-viduals equally divided between the two sexes.5 He also shows that if the total population were to fall much lower than this, new types of marriage, including marriage alliances normally forbidden, would either appear or develop in an exceptional way and produce new contradictions and social conflicts within society. Such a population decrease might be caused by epidemics, famines following an exceptional drought, the worsening of ecological and economic conditions after European conquest, and the introduction, for example, of extensive stock grazing which changes the animal and vegetable environment and upsets the balance of the resources of hunters and gatherers. The ‘action’ on kinship relations of the change in the material base of the societies thus leads first to a modification of marriage practices, but this modification takes place only if the transformations of the material base result in a lowering of the total population below the level compatible with the normal reproduction of the kinship system.

Two theoretical conclusions not considered by Yengoyan may be drawn from this analysis. First, it shows clearly that changes in the material base do not uniformly affect kinship relations—either the diverse elements which compose them or the discrete spheres of action which they organize. Marriage practices are the first part of the system that is modified. This may produce changes in residence, but in the two cases above rules of filiation remained intact. This confirms Morgan's findings: relationships of consanguinity change less quickly than those of alliance6 and, since modifications in the system of alliance are immediately reflected in the family, new types of family appear at the same time as do new alliance rules.

Second, the action of a change in the conditions of production on the most dynamic element of kinship relations, alliance, is only possible if these changes have previously upset the demographic conditions neces-sary for the reproduction of the kinship system. The demographic constraints internal to kinship relations thus constitute a necessary mediation for transformations of the material base to affect alliance relations.

These two analyses reveal4 relations of order ‘ existing among diverse structural elements of society. These relations of order ensure that the determination by the material base is mediated by unintentional objective properties of the other levels, and produce differentiated, heterogeneous effects in the conditions of reproduction of these levels. It could be said that before reaching such general, theoretical conclusions we should at first ensure that Yengoyan's findings are correct. They have, in fact, been shown to be right on two occasions. His findings have been tested against demographic data collected by anthropologists working in subsection systems, and not only were they proved correct but they have removed an apparent contradiction or at least severe disagreements concerning the data. Among the Walbiri, a central desert group studied by Meggitt in 1954, the whole population was then approximately 1,400, that is to say more than the 1,070 necessary for the normal functioning of the system. As could be expected from Yengoyan's calculations, 91·6 per cent of marriages followed the rule of preferential marriage with the second-degree matrilateral cross-cousin (Meggitt 1962, 1965, 1968). By contrast, among the Angula of the Gulf of Carpentaria, studied by Mary Reay in 1958–9, only 57·95 per cent of marriages followed the rules, and this was in a group which, as a result of the drastic effects of contact with Europeans, numbered only 288 individuals (Reay 1962).

In a more recent work, Yengoyan (1972a) has given supplementary proof of the accuracy of his analyses by showing the effect of the reversal since 1950 of the constant decline in aboriginal population which started in 1788 following the first contact with Europeans and continued right through until the 1930s. Since then, as a result of sedenterization in reservations (due to more or less disguised compulsion on the part of missions and government—see Jones 1965, 1970), where they have had to rely on government hand-outs, change of diet, increase in birth frequency (due to settlement), and the drop in infant mortality (due to increasing control of epidemics and diseases), the population has begun to rise sharply, so that today the birth rate is almost 3·5 per cent per annum. This has resulted in the groups that have not lost their essential tribal structure, such as the Pitjandjara, gradually reactivating their former marriage rules and intensifying ceremonial practices (Yengoyan 1970). This politico-religious phenomenon expresses of course the desire of these groups to reaffirm their cultural identity and to resist the destructive pressures of the process of domination and acculturation they have undergone, which has deprived them of their land and subjected their ancient religious and political practices to a systematic process of erosion and destruction.

We should not forget, however, that this reactivation of the traditional kinship system in its formal aspect only occurred when the demographic conditions permitted it, at a time when the traditional economic infra-structure was not just gravely dislocated and in the process of rapid collapse (as it had been during the first stages of contact), but had...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Theory of Anthropology

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- General Editor's Note

- Introduction

- Note on References

- Empiricism and Historical Materialism

- Class and Class Consciousness

- Dominance Determination and Evolution

- Biographical Notes

- Name Index

- Subject Index