eBook - ePub

Language Variation and Change in a Modernising Arab State

The Case Of Bahrain

- 244 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First published in 1987. This is monograph 7 in the Library of Arabic Linguistics. The author gives a prime exponent of the Labovian sociolinguistic approach in the Arabic field and this present study is the culmination of years of work on the dialects of Bahrain, following his four previous articles on the subject. He takes account of variability in the language of individual speakers both in the direction of the spoken dialects and in the direction of Classical Arabic and his approach takes into account factors of nationality, religious group affiliation, and occupational class in the selection of linguistic variables and is thereby squarely in the camp of the sociolinguists.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Language Variation and Change in a Modernising Arab State by Clive Holes,Holes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Variation in spoken Arabic

This chapter is a brief review of work in descriptive Arabic dialectology relevant to a sociolinguistic study of Bahraini Arabic, and of studies whose aim has been to describe how speakers of Arabic, of whatever provenance, shift between different styles as the topic and social context of conversation change. Both of these types of study are germane to this work, which attempts to describe and explain the process of variation and change in one particular Arab society. My object in reviewing these works is not so much to criticise their findings, but rather to examine the data collection principles on which they are based and the descriptive procedures used to present results.

1.1 The traditional dialectological approach

If one thing has been learnt from the intense work in sociolinguistics over the last twenty or so years, it is that data collection techniques - what is collected, how it is collected, who it is collected from and who collects it - deserve the greatest attention if an accurate description (let alone explanation) of the vernacular speech forms used by any social group is to be made. The type of data collected, the physical and social contexts surrounding collection, and the identity of the researcher (native/ non-native) and the choice of subjects - all of these will have a direct bearing on what kind of language data is produced. Arabic-speaking speech communities are no different in this respect from any others. The researcher needs to be aware, through long-term participant observation in the community under study, of the linguistic effects which the factors mentioned above can have, if he is to build them into his research design and ultimately be able to explain the large amount of at first sight unmotivated variation in the spoken Arabic of his subjects, whether considered as individuals or groups.

The problems which arise from a failure to take adequate account of immediate context variables on the one hand, and the social structure of the community and the individual speaker’s place in it, on the other, affect traditional dialectological approaches to the study of spoken Arabic as much as they can more linguistically orientated ones. Some specific problems are highlighted below.

First of all, there is the question of what Ingham (1982:32) has referred to as the ‘multivalency’ of dialectal features. It has been observed (e.g. in Johnstone 1963, 1965, 1967; Al-Tajir 1982) that dyadic variables such as k/č, j/y, and even triadic ones such as q/g/j occur widely throughout the Gulf. The traditional dialectological approach has been to record such variation without any attempt at an explanation either of what social values the use of one or other variant has in any particular Gulf community, or at considering whether j/y variation in one country (say Kuwait) follows the same principles, and has a similar social or contextual significance to what it has in another (say Baḥrani). In the absence of any research methodology aimed at discovering which type of speaker says what, to whom, when (and ultimately why), the dialectologist is reduced to simply listing the forms which happened to show up in his data, and describing the least standard forms as ‘typical of the dialect’ (e.g. y<OA/j/) and the corresponding variant form (/j/<OA /j/) as betraying the influence of ‘other dialects’ or MSA. While it may be true that variation of the k/č or j/y type arose historically through the operation of the same phonological processes in all of the present day Gulf states, it is also true that the phonological conditioning on these processes differed from one area to another, and more importantly, that the present-day social significances of the use of the resultant forms (and hence their susceptibility to variation and ultimate replacement) differ considerably from Gulf state to Gulf state both because of differences in the distribution of ‘the same’ non-standard forms among high and low prestige social groups from one country to another and because of differences in the degree to which non-local forms of Arabic may have affected these countries’ populations (through the relative availability of modern education and television, for example). Thus, in Kuwait, the ‘normal’ dialectal reflex of MSA jīm for most native Kuwaitis in most circumstances is now an alveolar affricate /j/. The palatal glide /y/ may be frowned upon as ‘uneducated’ even though it is extensively used when Kuwaitis talk to each other. Thus for a Kuwaiti, /y/ signifies simply an uneducated or informal mode of speech. But in Baḥrain, while /y/ is certainly regarded by all speakers as ‘non-standard’, it is also basically a local marker of Sunni as opposed to Baḥārna (=local Shi’i) speech, which has ‘standard-like’ /j/ where the Sunnis have /y/. It is very noticeable that /y/ is retained by even highly educated Baḥraini Sunnis in all but their most classicized spoken styles, despite the pressure of MSA /j/. The explanation seems to be that a switch by a Sunni to /j/ could only be interpreted in the Baḥraini context as a cross-dialectal switch to Baḥārna speech norms (Holes 1980, 1983b). This, as an observer of the Baḥrain social scene would confirm, is a most unlikely event: where it does occur, it is in joking imitation of the Baḥārna dialect. Thus it will be appreciated that j/y variation is the ‘same’ phenomenon in Kuwait and Baḥrain only in the sense that some of the population of the territories which these two modern states occupy were once affected by a historical j→y change; but subsequent population movements and social developments have resulted in variation between /j/ and /y/ acquiring different social meanings.

A second problem with traditional Arabic dialectology is the assumption that the ‘most dialectal’ forms are to be found amongst the oldest and least educated members of a community, and indeed, the assumption that there is a stable set of ‘basic’ forms shared by them. This has been shown to be fallacious by many recent studies in other languages. No speaker in any community in which in-depth sociolinguistic research has been done (e.g. Labov 1966 (New York City English), 1972 (Black American English); Trudgill 1974 (Norwich English); Bickerton 1973a (Montreal French); Jahangiri & Hudson 1982 (Tehrani Persian); Russell 1982 (Swahili)) has been shown to be ‘single-style’. Whilst it is true that speakers may differ in the extent to which their speech changes as a concomitant of changes in some aspect of speech context, and that they may differ somewhat in the features they change, the major finding is that all speakers in all communities display some degree of variability (Hymes 1967:9). Even the oldest, most uneducated informant, it seems, has a repertoire of variant forms none of which can be considered more basic to him (whatever their historical status) than any other. All speakers, in short, appear to be ‘multilectal’ (to borrow a term from creolist linguists). If then, multi-lectal grammars are to be accurately described, data will need to be gathered in a variety of contexts which are different from each other, or in a single context in which there is a change in contextual factors.

A forthcoming study by Holes (1987) shows how, in the speech of a group of non-literates, pronominal enclitic forms show regular patterns of co-variation with changes in communicative intent, even in the space of a single ten-minute conversation. Such variation appears unmotivated and inexplicable if communicative intent is disregarded, just as, in the example quoted earlier, /j/ and /y/ variation in Baḥraini can only be described and explained properly if the social values associated with each variant are understood. Some old and uneducated speakers may, because of their age and isolation from or imperviousness to modern influences, preserve ‘old-fashioned’ forms of speech, but this preservation is likely to be partial and to differ in extent from speaker to speaker. Older and illiterate speakers, just like any others, are part of the speech community and more or less receptive to the changes occurring in it. They do not necessarily form a linguistically homogeneous group.

The purpose of these remarks, let me make it clear, is not to cast aspersions on the value of traditional dialectology as a separate and autonomous branch of linguistics, with its own tried and trusted methodology. Its chief advantage (e.g. Cantineau 1936, 1937, Johnstone 1967 for the Gulf and contiguous regions) is that it can provide a description of the characteristics of the dialects over a very large geographical area, which is useful in two main respects: the historical links of the dialects to Classical Arabic can then be investigated, and the typological links to neighbouring or more distant dialects (e.g. the sedentary/nomadic distinction)may be illuminated and may ultimately provide evidence for a demographic history of the area under study. But it is precisely because of its inevitably static, historical orientation to language study that traditional dialectology is methodologically ill-equipped to describe the linguistic variation and change which are the concomitants of present day social change, in anything more than an anecdotal manner.

The sociolinguist Dittmar claims that a major task for any theory of human language is to explain:

(a) how speech realisations are evaluated (privileged versus stigmatised status of speech forms);

(b) how languages change on the basis of such evaluations (revaluation versus devaluation of standard languages, dialects, speech behaviour of minority groups);

(c) to what extent language systems coexistent in the same community interfere with one another on the phonological, syntactic and semantic levels;

(d) how languages are acquired, conserved and modified on these levels;

(e) on the basis of what relationships language systems coexist and come into social conflict.

(Dittmar 1976: 104-5)

Aims such as these are not on the agenda of traditional Arabic dialectology, but clearly need to be addressed if any sense is to be made of the mass of co-existing and varying forms which characterise any extended piece of Arabic conversation. Dittmar’s concern is clearly explanatory rather than descriptive: he is arguing that we need to get at the mechanisms which underlie observed behaviour, rather than merely describe and classify what we observe on particular occasions. But if we now turn to work done on spoken Arabic which is outside the traditional dialectological paradigm, we find very few studies which have gone beyond taxonomy and attempted explanation. The reasons, it seems to me, have again to do with research design, data collection methods and the lack of suitable frameworks for the description of both context and linguistic variation.

1.2 Studies of interdialectal conversation and the stylistic continuum

Blanc’s (1960) study of interdialectal conversation was the first attempt to grapple with the problem of describing what speakers of Arabic whose native dialects are different do when they talk in order to ensure that they understand each other. On the basis of his data, which was a twenty-minute tape-recording of four Arab students at a U.S. university talking to each other on a pre-set topic, Blanc proposed a spectrum of stylistic formality ranging from ‘plain colloquial’ at the most dialectal end, through ‘Koineized colloquial’ to ‘semi-literary’ to ‘modified classical’ to ‘standard classical’ at the opposite extreme. Blanc’s data showed that, while the dialects at their most local diverge markedly from each other, the need to communicate clearly in an inter-dialectal situation leads speakers to suppress localisms in favour of more widely understood terms (not necessarily those of the interlocutors’ dialect(s)). Speakers are depicted as moving up and down this stylistic spectrum as the demands of the situation change.

There are, however, a number of difficulties with this approach. Blanc’s division of the gradient of formality into five blocs seems to have little a priori justification, (c.f. Versteegh 1984:32). As Blanc recognises, no inventory of the variants which belong to each bloc can be given, since some of the variables (e.g. vowel quality) are continuous rather than discrete and where variables are discrete (e.g. phonemic choices like /t/ versus /t/, or lexical pairs), the constituent variants cannot be unequivocally assigned to one part or another of the gradient: it is usually a question of a particular variant occurring more or less in one part of the gradient, rather than always or never. Style in spoken Arabic seems to be largely definable not in terms of the absolute presence or absence of particular linguistic features, but by the number of times features actually occur as a proportion of the times they could have occurred. The choice of one rather than another constituent variant of a variable does not, of course, happen in isolation. Spoken style is a set of mutually compatible (or as some sociolinguists would put it, implicationally ranked) choices which cut across all linguistic levels. Blanc, however, does not attempt to show how the choice of one variant might favour or constrain the choice of another. Talmoudi (1984), in a recent replication of Blanc’s work, but this time using North African speakers, again steers clear of the problem of describing the linguistic rules which underlie the ‘hybrid’ forms which are thrown up in cross-dialectal conversation.

Perhaps the most interesting recent work in the description of ‘medial’ Arabic is that done by the Leeds-based group of the 1970’s (e.g. Mitchell 1978; El-Hassan 1978, 1979; Sallam 1979, 1980), and in particular that of Meiseles (1980). Meiseles identifies three types of combinational process in structural mergers between MSA and vernacular elements. Firstly, there is the development of ‘symbiotic’ forms, in which for example, Egyptians combine dialectal verb prefixes such as /b/ -with MSA in an additive process, e.g.

wa naḥnu binaqu:l ‘anna

hal bta9taqidu:n ‘ann

hal bta9taqidu:n ‘ann

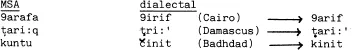

Secondly, there is the mingling of dialectal and MSA elements in words which belong to both codes:

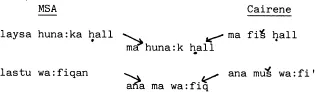

Thirdly, there are hybrid phrases based on the fact that expressions exist in MSA and the dialects which have the same immediate constituents but different surface realisations, e.g.

Meiseles considers (1980:132) that such blends are ‘(at least partially) controlled by a certain regularity. In other words, the blend belongs in part to the level of langue’

The examples above are clearly pitched at the standard end of the speech continuum. But there are many kinds of occasion when a more ‘dialectal’ feel is aimed at for social and communicational reasons. A case in point in Gulf speech communities is the language used on the radio in children’s programmes concerned with encouraging road-safety, regular school attendance, etc. The vocabulary in these admonitory pieces is largely standard, but the phonology and, to some extent, the morphology (especially demonstratives and negatives) is, it would appear, deliberately dialectal, in order to give more of a friendly feel to the warning. Here is an example:

/u ha:di ḥdatat bilfi9l/

‘and this in fact happened’

‘and this in fact happened’

Here the syllable structure of the verb is dialectal, though the verb itself is not (/ṣa:rat/ would be the dialectal equivalent); the demonstrative is morphologically dialectal; and /bilfi91/is standard. The whole phrase appears to be a dialectalisation of /wa ha:dihi ḥadatat bilfi9l/ through the application of dialectal morpho-phonological rules, where this is possible. Data of this type are interesting in so far as they can tell us a little about the linguistic strategies which speakers employ in just one of a wide range of speech contexts where neither a purely standard, nor purely dialectal variety of Arabic is communicatively appropriate. But to date, to my knowledge, no-one has attempted to collect extensive corpora of data in the variety of contexts within one speech community which would be necessary to build up a complete description of that community’s ‘rules of use’. In the absence of such a comprehensive description, the behaviour of particular speakers on a particular occasion will remain uninterpretable in many key respects.

To sum up, it seems to me that progress in the descr...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Transcription and Transliteration Systems

- 1 Variation in Spoken Arabic

- 2 Bahrain: The Social and Cultural Background

- 3 Data Collection Methods

- 4 The Social Distribution of Some Ba Phonemes

- 5 Phonemic Variation: Analysis and Interpretation

- 6 The Social Distribution of Some Ba Morphophonemic Patterns

- 7 Morphophonemic Variation: Analysis and Interpretation

- 8 Morphophonemic Rule Formulation

- Bibliography

- Index

- Glossary of Technical Terms