![]()

Part I

Introduction

![]()

Chapter I

A Mosque Of Their Own: Muslim Women, Chinese Islam and Sexual Equality

‘For Our Muslim Sisters’

It is not as if we know of no quest, no ideals;

we are like many others yearning for the daily sun,

in our dreams fulfilling our most beautiful aspirations

only because of the prejudices of this world,

must we confine ourselves to the kitchen, idling away the sunlight?

ah, Muslim sisters –

when today, the surging tides of the reform

are pressing on the shores of our motherland,

and our fellow believers so as to promote the cause of their people

are at work day and night,

How can we

confine ourselves to the closed courtyards?

may the eyes of the world

stare us into faltering,

but for Islam

we must go forth to meet the movements of change,

ah, Muslim sisters –

let us go out of this door to purify ourselves in the light of sun,

release our life-energies,

give our existence still greater meaning,

and our life, splendour.

Sisters, let us walk arm-in-arm! (Lu & Wang, 1993)

Lu Jiye and Wang Hailan, writers of the poem which appeared in Minzu Yilin (a magazine devoted to ethnic minorities’ arts and literature), address their ‘sisters’ as Muslims, as active participants in current reforms, and as Chinese women. They call upon them to brave prejudices and cross the domestic threshold separating them from realisation of cherished aspirations. Islamic rites of purification fuse with Maoist calls to emancipate women from fetters of patriarchy, creating a potent imagery of liberating sun light with the power to purify and release energies that are life itself. Women are implored to extend their site of activity beyond the home, making the world their own: for Islam, for the cause of reform. The site of change must be the world itself: women’s visibility in social spaces outside family homes; women’s yearning for life beyond confinement; women’s capacity for subjective intervention in times of political, economic and social changes to create opportunities of transformative potential for themselves; women’s relationship with their fellow believers in pursuit of a common cause, Islam; – this remarkable poem foreshadows some of the most important themes in our book.

We ask how unique and controversial innovations in organised Islam in China led to the historical emergence of qingzhen nusi (abbreviated: nusi, women’s mosque) and the institution of nu ahong (female religious leader, often presiding over a nusi, with ritual, educational, social and political functions); we ask about initiators, initiatives, place and time of innovations (see Chapters II, III, IV), the structural and historical factors of its evolution. But also we ask what happened when Muslim women took over space situated outside their designated feminine sphere which was intended for their education and which became in the course of time a site of religious and social activities over which women had, and have, various degrees of control and influence, in various degrees of dependence on, and independence from, men’s mosques (see in particular Chapter VII). In foregrounding women-centred viewpoints, the concept of nusi widens to encompass meanings beyond a social space allocated to female Muslims to acquire religious learning and ritual mastery, to perform ablutions and pray collectively under the guidance of their own ahong: that is, the religious values and spiritual meanings invested in the site of prayer which reveal the subjective imprints of different generations of worshippers and religious leaders. The mosque understood as ‘a perspective’ originated in and turned towards the divine (Fatima Mernissi, 1996) symbolises the dynamics of an institution which straddles historical contingency and an unending quest for eternal truth, which is sustained by faith in creation ordained by God, on the one hand, and yet, on the other hand, when it comes to institutionalised religion and religious praxis, is subject to situated interests and contested claims of authenticity which engender their own dialectics: oppositional, interventionist agency as alternative and challenging re/interpretation of the divine will.

In speaking of women’s perception of the past, Fentress and Wickham identify the most essential problem as being ‘hegemony: that of a dominant ideology and a dominance over narration, as expressed through the male-female relationship’ (1992:138). The relationship between the specific ‘hegemony’ which characterises relations between men and women in Chinese Islam, and its interfacing with the sexual asymmetry characteristic of Confucian culture, and how it effects women’s memory, raises questions of appropriate methodology (see Chapters XI, VIII). In writing about history, we must write about silence, devising ways of recovering the past ‘on the basis of documents and the absence of documents,’ Le Goff notes (1992:182).

But muted memory is not the same as inactivity, or lack of agency. Muslim women look back on a memory archive, even if overwritten and partial, of buildings, religious schools and women’s mosques, many several generations old, under female religious leadership, which present a powerful visual documentation of challenge to the androcentrism of Islam (for interesting parallels in dearth of scholarship on medieval European nunneries, see Gilchrist, 1994). This evocative ‘symbolic landscape’ of Chinese Islam is inspiring some Muslim women intellectuals to formulate the beginning of their own unique Islamic tradition and indeed with an understanding of conditions of Muslim women elsewhere, a pride that uniquely allows Muslims in China to look back at a consistently strong female presence in Islamic organisation (foremost with her pioneering article, Shui, 1996; also, Jiang Bo & Wang Xingling, 1996).

This landscape of ‘women’s mosques’ provided us, the researchers, with not only symbolic but also physical and social pointers to a greater understanding of how women engendered and sustained faith, aspiration and loyalties under often challenging conditions.

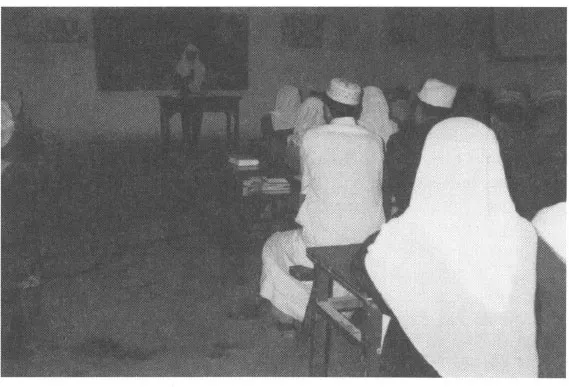

PLATE 2: A young female hailifan (student) lectures a mixed class on the topic of ‘Obey and Respect Your Teacher’; at the Hexi Mosque, Zhoukou City, Henan Province. 10 October 1996 (Shui)

The Book: Researchers and Methodologies

Shui Jingjun had been asking questions about the origin of women’s mosques since the late 1980s, investigations which culminated in the publication of an article in 1996 in Huizu Yanjiu. But due to lack of institutional and financial support the work was based on partial data and too small a sample of women’s mosques to allow more than tentative conclusions. Maria Jaschok’s interest in the situation of Muslim women had been sparked by an accidental discovery of qingzhen nusi (women’s mosques) in Zhengzhou, Henan, in 1993. Han colleagues’ indifference to religious women, lack of documentation, and an enduring interest in the lives of believing women in a secular society provoked further enquiries. On one of her early visits to a women’s mosque in Zhengzhou, Guo Ahong (the resident spiritual leader, teacher and ritual specialist) refused, as she put it, to repeat herself, and thus brought two researchers together who had, unbeknown to each other, interviewed Guo Ahong on very similar concerns. It was then, as appreciative informants were wont to say, through the intervention of Allah, that we met. We decided to collaborate.

The identity of participants is important to understanding the formulation of a project. We shape methodology, raise questions and interpret findings (see Eck and Devaki Jain for their discussion of such issues, 1986). The consequences for ‘naming of issues’ and cross-cultural translation became also apparent in our collaboration as we sought to translate across cultures and convictions of multi-faceted political, religious, and secular hues. Of different ethnic and religious backgrounds, of different nationalities, academic training, assumptions and institutional and political constraints – our differences not only complemented each other, enriching the collaboration for both of us, they also fuelled our dialogues which became a vital component of a work-style which enabled long and fruitful discussions and facilitated a close, and trusting, co-operation. Not always did we agree, but our disagreements proved creative and the grist for the conversational mill. Over time, boundaries which separate insider from outsider began to shift. The amount of time spent in Muslim households, in women’s mosques, was an education in ‘conformity’, as Lila Abu-Lughod (1988) tells of her own process of integration into the community of Bedouin women in the process of which, by becoming more ‘like’ the community, she came to discover what the community’s priorities are – and thus what they must become for the researcher.

Shared weeks of fieldtravel, constant dialogue, the joint confrontation of obstacles and crises, knitted the bonds between us more tightly, enabling us to be spontaneous to the point, on one memorable occasion, when we erupted into a rather public emotional disagreement, enabling us to be both mutually critical and affirming of each other. Insider/outsider divides realigned themselves when, towards the latter part, two young Han scholars were invited to join in the work. Wang Yufen and Zhu Li contributed their expertise in legal and economic history respectively to explore the place of Islamic law in the lives of Chinese Muslim women (Chapter VI) and to examine the internal administration and scope of authority of nusi in terms of degree of dependency on men’s mosques (Chapter VII). Tension built up at times more difficult to resolve, because intrinsic to the way Han identity, in this case, unknowingly, tends to defined itself as an Othering of minority identity. These conflicts were a source of enlightening discussion and a sobering lesson for all on the precariousness of scholarly objectivity.

The time allowed by our three-year framework, our repeat visits to mosque communities, our correspondence with scholars and official cadres (not all were adversaries), enabled many Hui Muslim local historians to assist us, trace informants or a piece of missing information, a document, a photograph – as it happened with Guo Chengmei, the son of a famous ahong family. Guo, a cadre working for the Jiaxing Branch of the China Islamic Association and a respected Hui historian, painstakingly reconstructed Yang Huizhen Ahong’s dramatic impact on the Jiaxing Muslim community during the 1940s to be included in our book (see below and Chapter XII). Two life testimonies were written by the women themselves: Yang Yinlian from Harbin gave us her work-report as nu ahong for inclusion, and Shui Zhiying from Nanyang in Henan recalled the impact of several generations of women in her husband’s family on her own spiritual journey (Chapter XII).

Aware of the importance of decoding incongruities, tensions and frustrations in collaborative work for a constant re-examination of our respective a priori assumptions about research priorities, work-style and methodologies, we took on board Daniel Overmyer’s warning in his state of the field article on the study of religion in China (1995), namely, that religious studies must inevitably entail Orientalist praxis (due to the dearth of pertinent Chinese scholarship). Our collaboration involved an important component by which conversations about our fieldwork incorporated also questions of the other’s bias and of sources of disagreement over interpretations. Indeed, as Kamala Visweswaran puts it, ‘questions of positionality more often confront female rather than male fieldworkers’ in that feminist scholars are concerned as a matter of methodology with biases, silences and distortions in representations of culture, and their recognition of cultural interpretation as ‘power laden’ (1994:23). The vulnerability of local colleagues under constrained conditions of academic production was a factor which affected judgement of feasible (as opposed to desirable) ethnographic work and the moral choices to be made when foregoing a research site was to sacrifice valuable data to concerns for the project’s (and at times, researchers’) safety. A volatile context of fluctuating policies on ethnic and religious rights in China, often instant official responses to specific local events, made flexibility in research planning and willingness to alter schedules and intended list of informants an imperative. This constant wariness also served to minimise potential negative impact on the continuation of the project due to its frequent sudden politicisation, brought on by the presence of a Western researcher.

The collaborative nature of our project made us conscious of different audiences and different expectations as well as the different impact our publication was bound to have: with audiences ranging from the local Muslim community (a most attentive and at time interventionist audience) and orthodox imams to Western secular feminists and Muslim feminists. We had to ponder how publication might effect the situation of women’s mosques and female ahong. Could international Islamic funding agencies, the religious authority attached to Arabic Islamic pronouncements, exert pressures for change? Already certain sensitivities are apparent wherever Muslim congregations in large Chinese cities are international or funding from Arab Muslim countries is hoped-for. But Muslim women confidently place their trust in the Chinese government and its continued implementation of the official policy on religious self-rule which, so they maintain, will fence off undue outside interference. For female religious leaders, bargaining with patriarchy is steeped in decades of useful political experience.

Our methodology arose from project-related contingencies, scarcity of scholarship (international and Chinese, see Chapters II, III) and most crucially from our women’s studies perspectives, guided by what Janet Bauer calls the ‘metaphor of agency’ (Bauer, 1997:223), that is, reliance on ethnographic work and focus on individual life testimonies.

But ethnographic and oral history methodology needed supplementing with historical research and textual analyses. Clearly from the few studies which deal with women and Chinese Islam, urgent questions had not been asked concerning the internal constitution of Islamic organisation (see Pang Kong-Feng’s study of Hainan’s Utsat Muslim women, 1997) and entirely lacking was an historical perspective on the genesis of women-centered institutions not a part of Islam elsewhere (absent also in Alles, 1994). An historical reconstruction was necessary which involved a close analysis of seminal works which form part of the corpus of Chinese Islamic knowledge, entirely male writing. Making use of the periodisation of Muslim history defined by the Hui historian, Bai Shouyi (1985), we situated the various use-values assigned to Muslim wives and mothers within specific, shifting political and cultural configurations defining historical relations between successive imperial administrations and Muslim populations in the context of which women came to be ‘boundary subjects’ (Julia Kristeva, 1993) of a re-imagined and re-invented religious and cultural identity (Chapters III, IV).

The Book: Authorship and Perspectives

We have felt it important that the book reflect our differences in background, cultural identity and academic framework of reference. We did not want a collaboration across cultures, religions and academic disciplines, and our dialogue over differences, to disappear into a homogenised, therefore distorted, authorial voice which in consequence would not have represented either of us.

When Shui Jingjun reconstructs the genesis and subsequent development of women’s religious culture in zhongyuan diqu (Central China; Chapters II.2, III, IV), her reading of women’s religious rights, attainments and predicaments, is rooted in an understanding of sexual solidarity which for her underpins ethnic and religious Muslim solidarity and commonality in defence of Islam, whether against explicit hostile aggression, forcible assimilative policies, or the even more subversive threats of secularism and modernity today. In Shui’s interpretation the origin of women’s high visibility thus lies in the unity of purpose felt by men and women in the face of external oppression and danger of assimilation during the sixteenth century, the ‘era of adversity’ for Hui Muslims in China. Her characterisation of male-female relationships in the light of early stress on female education, growing number of Koranic schools for women, training of women to enter the ahong profession and, then, in mid-nineteenth century, a mosque as a separate site of worship only for the use of women, is indicative of an underlying theme of harmony between women and men, mutual help and joint effort to serve Allah. Benefiting both.

Jaschok’s reading has been influenced by scholars such as the postcolonial critic Mervat Hatem (1993), whose a...