![]()

Part III

Contact Linguistics

![]()

Chapter Five

Multilingualism in Palau: Language Contact with Japanese and English*

Kazuko Matsumoto

1. Introduction

This article provides the first investigation of contact-induced language shift in a multilingual Palauan community in the Western Pacific. Owing to its history of occupations (Spain 1891–9; Germany 1899–1914; Japan 1914–45; the US 1945–94), its lately achieved political independence (as the Republic of Palau in 1994) and its economic reliance on prolonged financial support from the US and Japan, a rather unique and interesting language contact situation has arisen.

Most older Palauans are Palauan-Japanese bilinguals, but since 1945 competence in Japanese has diminished rapidly, leaving many middle-aged Palauans as ‘semi-speakers’, and the younger islanders, who are bilingual in Palauan and English, as formal L2 learners. The legacy of the Japanese language period, however, has been very heavy lexical borrowing from Japanese into the Palauan of the middle and younger aged islanders. On the other hand, English has, to a great extent, replaced the Japanese language as the official and international language in Palau and in Micronesia as a whole, strengthening its symbolic domination in a range of formal social institutions, such as law, literacy and education.

The purpose of this article is twofold. First, it aims to draw a sociolinguistic profile of this new Pacific Island nation, by locating the underlying salient themes of multilingualism. Second, it attempts to explore the social processes underlying language maintenance and shift, by examining not only which social changes in a wide-scale historical and political-economic context can lead to rapid language change, but also how a complex web of a speaker’s socio-demographic factors and language ideology may tip the linguistic balance.

An ethnographic questionnaire survey was conducted in the capital, Koror, in 1997 and 1998. Both quantitative and qualitative analysis was then carried out. Descriptive and inferential statistical tests were employed to examine a range of correlations amongst social dimensions and language behaviour in the community. Social variables included are age; sex; ethnic family background; ethnic identity; face-to-face interaction; distant contact; language opinions; education; and consumption of the mass media.

I shall first briefly explain the background of Palau. I shall then describe the methodology that was adopted specifically for this questionnaire language survey. The third section will be devoted to defining the social and linguistic variables. Finally, I shall ethnographically and statistically examine the findings, with the use of SPSS version 9.0.

2. The background of Palau

The Palau Islands are an archipelago located in the Western Caroline region, with a population of 17,000 (The Office of Planning and Statistics 1997, Table 1).

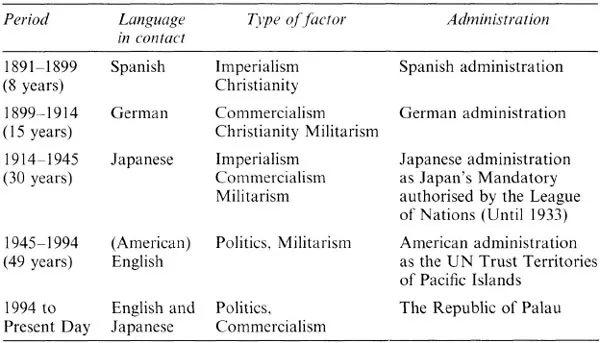

Table 1 Language Contact History in Palau

The language contact situation in Palau has been imposed by a century of colonial domination by Spain, Germany, Japan and the US. Table 1 summarises the relation between prime source languages and factors that engendered language contact in a chronological order.

Although Palau finally became an independent nation in 1994, the impact of Japan and America appears still to be of significance for Palau. This seems to be for three reasons: first, the recentness of their colonisation; and second, the prolonged financial support from both countries upon which the Palauan economy still heavily relies. For instance, aside from war compensation, Japan has provided Palau with free financial and technical aid through the Overseas Development Administration (ODA) since 1982 (Kobayashi 1994: 223). Particularly since the Japanese-Palauan, Kunio Nakamura, became the President of the Republic of Palau (1994 — present), a closer relationship between Palau and Japan has been reported1. The US, on the other hand, has supplied financial aid to Palau, first as the trustee of the UN Trust Territories of Pacific Islands (TTPI), and second in return for provisions for US military access to Palau on the basis of the Compact Free Association since 1994 (Wilson 1995: 30–36).

The third reason why these two nations have a strong impact upon Palau concerns the strategic educational and social reforms that Japan and America embarked upon in Palau during their administrations. Since both countries identified Palau as a key strategic site for military purposes, they implemented administrative policies designed to maintain permanent access to Palau. More specifically, both countries introduced and, in effect, put into practice their own law and school systems with textbooks and teachers from their homelands, and enforced their languages, namely Japanese and English, as the official languages in Palau. Not only were their languages imposed as the languages used in the classrooms, but also the patriotic rituals of Japan and the United States were instituted in Palau through education, such as Chokugo 勅語(meaning ‘Imperial Rescript,)2 and the US-oriented curricula (Imaizumi 1994a: 34; Wilson 1995: 27; Solomon 1963: 5–16). Moreover, programmes to bring the meteet (i.e. high chiefs and high-ranking clan members) on tours to Japan and to provide grants for an increasing number of Palauans to travel and study in the US were organised, with a clear aim of making the Palauans pro-Japan and pro-US, respectively (Imaizumi 1994a: 29; 1994b: 568; Solomon 1963: 22, 47, 52).

In terms of socio-political reforms, however, the Japanese and American governments each took different approaches. The Japanese government formed a new political hierarchy in conjunction with the traditional Palauan clan system and the Japanese imperial system (Toyama 1993: 57–9). High chiefs were authorised as sôsonchô 糸村長(meaning a ‘head of village chiefs,), while high-ranking clan members were classified as sônchô 村長(’village chiefs, ) and paid salaries by the Japanese colonial government (Francis & Berg 1980: 437; Toyama 1993: 57; Imaizumi 1994a: 37–9). That is, a chain of command ran from the Minister in Japan to the governor-general in Koror, down to the officials of the various branch offices for each island, ending with indigenous meteet appointed as head-chiefs and village chiefs (Francis & Berg 1980: 437–43). By contrast, the US led the Palauans into a new social order of democracy, i.e. an electoral government.

Another important difference between the Japanese and American domination can be seen in the different degree of daily interaction between the Japanese and Palauans and between the Americans and Palauans. First, there was a massive influx of Japanese civilian immigrants into Palau during the Japanese administration, while no immigration took place in the American period. Japanese immigrants outnumbered Palauans in an approximate ratio of four to one in 1941; in other words, about 24,000 Japanese and 6,000 Palauans were living in Palau (South Sea Bureau 1942: 36–7). Second, the majority of these Japanese immigrants were farmers and fishermen who were recruited from Japan as a major labour force and who worked with the islanders in Japanese enterprises in Palau (Francis & Berg 1980: 438; Shuster 1978: 9). In contrast, the small number of Americans, who were temporarily stationed in Palau, were the military and administrative personnel, missionaries and school teachers.

In addition, the settling pattern of these Japanese civilian immigrants in Palau was different from that which took place in other former Japanese colonies in Asia, such as Korea and China, in that they lived with indigenous Palauan residents in the same community, rather than in an established and exclusive Japanese community. There was no recruitment of comfort women in Palau; instead, marriages between Japanese men and Palauan women were encouraged and rewarded by the Japanese government (Toyama 1993: 54–65)3. Thus, the degree and frequency of everyday interaction between the Japanese and Palauans appears to have been far greater than with that of Americans.

Currently, the official languages in Palau are Palauan and English. However, the Palauan Constitutional Law (1979) indicates that English in judicial and administrative matters ought to prevail over Palauan. Therefore, all official documents and reports have to be written in English. Only one local Palauan newspaper (Tia Belau) is written solely in English, with the exception of Palauan words used in the cartoons. The language used in high school is still mainly English, with American textbooks being used and American history and geography taught. English is predominantly used throughout higher education in Palau.

In schools, it was not until fairly recently that an emphasis was placed on the importance of their indigenous language, Palauan, by editing Palauan textbooks and teaching school subjects in Palauan. Japanese is now taught as the first foreign language in schools, in addition to English and Palauan.

The development of a Palauan orthographic system has been controversial, and no system has yet been fully agreed upon and stabilised. Since Palau is traditionally an oral society without writing systems, similar to almost all of the languages in the Micronesian region, Palauan literacy was only introduced by the former colonial powers during the early twentieth century. During the Japanese period, Japanese kana syllablaries (katakana and hiragana) functioned as phonograms in Palauan, while during the American administration the Roman alphabet became a new Palauan orthography. As a result, all of the official ballot papers for the 1992 and 1997 general elections in Koror, Melekeok and Angaur States used a dual writing system for Palauan (the Roman alphabet and the Japanese katakana), with Palauan-English bilingual instructions.

Thus, during the last century, the Palauan community experienced dramatic social, political and demographic changes as well as intensive language contact with the Japanese and English, due to colonialism. We will now examine in depth how the past and present relationships between Palau and the former colonial nations have contributed to the formation of the current mu...