eBook - ePub

The Taking of Hong Kong

Charles and Clara Elliot in China Waters

- 316 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Relations between Britain and China have, for over 150 years, been inextricably bound up with the taking of Hong Kong Island on 26 January 1841. The man responsible, Britain's plenipotentiary Captain Charles Elliot, was recalled by his government in disgrace and has been vilified ever since by China. This book describes the taking of Hong Kong from Elliot's point of view for the first time '- through the personal letters of himself and his wife Clara '- and shows a man of intelligence, conscience and humanitarian instincts. The book gives new insights into Sino-British relations of the period. Because these are now being re-assessed both historically and for the future, revelations about Elliot's role, intentions and analysis are significant and could make an important difference to our understanding of the dynamics of these relations. On a different level, the book explores how Charles the private man, with his wife by his side, experienced events, rather than how Elliot the public figure reported them to the British government. The work is therefore of great historiographical interest.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Taking of Hong Kong by Susanna Hoe,Derek Roebuck in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Ethnic Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

WHENEVER THERE IS A BREEZE

‘The wretched weather and very heavy state of the roads detained us on our journey some hours longer than is usual,’ wrote Charles Elliot to his sister Emma Hislop on 18 January 1834.

Captain Elliot, his wife Clara and their children were about to sail on the Andromache from Devonport, the naval base near Plymouth on the south coast of England, to Macao, the small Portuguese enclave on the south coast of China – 7,000 miles away. When the Andromache arrived in Macao six months later, the weather there was as different as possible – almost unbearably hot and humid – and, just before the Elliots left China waters seven years later, Charles was shipwrecked by a typhoon and, as a result, nearly murdered for a reward.

Captain Elliot had been appointed, in late 1833, to the staff of Lord Napier, His Majesty’s Chief Superintendent of Trade in China, as Master Attendant – a position in which he would be involved with British ships and crews operating between Canton and Macao. Lord Napier was also to sail in the Andromache; and he, too, was taking his family with him.

The rest of the Chief Superintendent’s staff – Second and Third Superintendents, and the Commission’s Secretary – were already based in Canton, the Pearl River port, and Macao. They had been part of the British East India Company whose monopoly on the China Trade, hitherto safeguarded and directed by an Act of Parliament, was coming to an end.

Lord Napier had been asked by the British Government to go to Canton to negotiate terms with the Chinese Government which would replace the East India Company arrangement. By these terms, Britain’s now more general trade with China could be kept orderly and extended into a new era.

On that first evening in Devonport, Charles continued his letter to Emma, who lived at Charlton Villa near Blackheath, south of London:

We have this moment arrived, and to sure post which leaves at 5 o’clock in the morning I scrawl these few lines. The dear little ones behaved (as I am sure you will let me say now that we are fairly off, to return God only knows when) like angels. Harriet has coughed less today but she is uncomfortably feverish this evening. We have dosed her with scammony and put her to bed. Hughie is well, some slight degree of cough excepted. Clara and her handmaid are less tired than you might expect. I have not seen [Captain] Chads; indeed, we have only been here a quarter of an hour, and I will not disturb him this evening.

And now, Dearest Emy – adieu. Kiss our beloved little fellow [Gibby] for us. I am sure you will be a mother to him, but I will not write upon that subject now. God in heaven bless and protect him. Write to Harriet [their sister] to tell her of our first safe step in this Chinese pilgrimage.

signed your ever most affectionate Charles Elliot

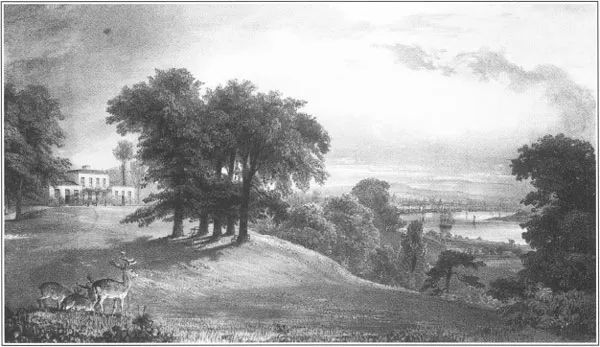

Plate 1 Charlton Villa c1850 – (land surveyor’s engraving) courtesy of Greenwich Council Local History Library.

Five year old Harriet, also known as Chachy, and her two year old brother Hugh (Hughie) were accompanying their parents to China; Gilbert (Gibby), the new baby, was to stay behind with his nanny, in the charge of his aunt Emma, her husband General Sir Thomas Hislop, and their daughter Nina.

A week later, the Elliot and Napier families were still detained in Devonport; the Andromache (captained by Henry Chads, an old friend of the Elliot family) had not yet sailed. But, perhaps surprisingly, there had been little communication between Captain Elliot and Lord Napier. Elliot could not help noticing this development and commenting upon it. He wrote again, on 25 January, to his sister Emma, starting with the apologies, and continuing with witty allusions, quotations in French, and sharp observations about his superiors that were to become a feature of their correspondence:

My dearest Emy,

Many kindest thanks for your affectionate letter, and I would make many excuses for the rareness of my own communications, if I did not know that you can so easily sympathise with my infirmity as a correspondent. We are going on pretty slowly to the completion of our equipment, and after all, it does not signify that we are not quite ready, for these boisterous easterly gales would, or at least should (in all reason) detain us snugly in harbor.

The day after my arrival I called upon Lord Napier, but he has not returned my visit, and as Clara’s visit to Lady Napier also remains unnoticed, I presume there can be no great eagerness to cultivate our acquaintance. We met them on Thursday at the Admiral’s, but they made no excuse upon the subject, and perhaps therefore, they mean to establish it as their Canton etiquette, that they do not return the visit of the Master Attendant and his Lady.

Be that as it may, I shall understand this matter in plain English, and if they forget to visit us, why I shall not remember to visit them. I am very ready to make the koto [formal Chinese obeisance] to the brother of the sun and moon [Emperor of China], but I don’t perceive it can be necessary to perform any more extravagant prostrations to the Bedchamber Lord [Lord Napier] of the Glorious Neptune of these Isles [King William IV] than men are wont to call – a bow.1

However, I must not say any more about this or else you will declare I am angry, and to be angry for such a wherefore, would assuredly be somewhat vulgar. If they like to cultivate us, we are quite ready to furnish them as much social fruit, as the soil can be made to produce, and if they please to leave us alone, we are willing to pass on our way.

I thought Lady Napier still very pretty [she was 40], with just the sort of manner and conversation which all the rest of the 120,000 well bred people in this country usually have. The young ladies [Maria and Georgiana Napier] I did not see.

And now I believe I have carried you to the end of my chapter on the great ones of our party, and you know, I always accused you of being somewhat anxious upon these points, so I have felt myself called upon to let you know whatever was to be said about them.

Now pray dear dear Emy, pray do not imagine I am angry or brooding moodily over fancied slights. I am quite at my ease about all wrongs, real or imagined. Voltaire says, ‘On s’est épuisé à écrire sur la grandeur selon ce mot de Montaigne “Nous ne pouvons y atteindre, vengeons nous pas en médire”.’ [‘Enough of writing about the nobility; according to this mot of Montaigne “If we cannot get there, let’s not take revenge by slander”.’] It is very true that my chance of attaining it is considerably diminished, but I cannot visit my own mischances, and it may be. the unfairnesses of others, upon the mighty ones in whose train I am to go [to] the antipodes.

I have told you of this affair of the visiting not because I can make it interest myself, but because I thought it might interest or rather amuse you. I dare say the Napiers are very good sort of people for all these delinquencies nevertheless and notwithstanding, and whenever they want us, (and poor things I know enough of the loneliness of far off places to be sure they will want even such as we are) they will find their way to us, and we will be ready to come to them.

So, who exactly was Charles Elliot and why should he, a mere master attendant, feel slighted at not being drawn naturally into the charmed circle of Lord Napier, the leader of the British mission, and his family?

Charles Elliot was a first cousin of the second Earl of Minto (Gilbert Elliot) who at that time was British Ambassador in Berlin but about to be appointed First Lord of the Admiralty. Another cousin was Lord Auckland (George Eden), then First Lord of the Admiralty and about to be appointed Governor General of India, a post in which he would have responsibility for British activities in China waters. Charles was also closely related to the Earl of Malmesbury.

This network of cousins explains Charles Elliot’s family pedigree and why he might have expected Lord Napier to have been more friendly during an enforced delay. But also of interest to this biographical sketch were the 33 year old Elliot’s more direct parentage, his experience up to 1834, and his wife.

His father Hugh, a brother of the first Earl of Minto, was a colourful, rather unusual sort of nineteenth century diplomat, for he was not always entirely diplomatic, and he was not a conformist in either his career path or in family matters.

Charles was born in 1801, while his father was posted to Dresden. But the mother of eight of Hugh’s children was his second wife. His first marriage to a Prussian heiress while he was posted to Berlin was against the wishes of both families and came to an unhappy and violent end when she ran off with another man and Hugh challenged him to a duel. He then divorced her, at a time when divorce was not easy or common.2

Charles Elliot’s mother seems to have come from a more ordinary family and the reference books cannot agree it she was called Margaret Lewis or Jones. Elliot’s niece, Nina (Emma Hislop’s daughter) was later to write a biographical sketch of her great uncle Hugh based on his letters and those of other family members. Nina wrote of a visit of Lord Minto to his brother in Dresden in 1799: ‘Some years had passed since the brothers had met, and in the interval Hugh Elliot had married a beautiful girl of humble birth, but whose personal qualities justified his choice.’3 His father’s choice might be of less interest if Charles, too, were not, in due course, to make an unusual marriage, of defiance rather than of convenience.

In spite of the fact that his father was a diplomat, and though he, too, was later to be employed in the foreign service, Charles went to sea first. He was left at boarding school in the United Kingdom when his father went to be Governor of Madras in 1814, taking most of his children.4 But by the age of 14 (in 1815), Charles Elliot was at sea.5

During the years in the Royal Navy that followed, Elliot gained the experience that underpinned his later career. One of the main peacetime functions of the navy was patrols against the Atlantic slave trade which had been formally abolished, as far as Britain was concerned, by an Act of Parliament of 1807. By 1821, Elliot was serving off the West coast of Africa; in 1823, he moved to the West Indian Station. He served in the Caribbean, where the slave trade was rampant, and until 1828 was based off Port Royal in Jamaica. He was promoted then to the rank of post captain. Such service was sometimes exciting, sometimes tedious, and always dangerous to health. Charles Elliot made the most of the experience, particularly as captain of the Harlequin.6

By 1830 Elliot had left active service in the Royal Navy and been sent by the Colonial Office to Demerara in British Guiana to be Protector of Slaves (and a member of the Court of Policy). That posting begins to explain the rest of his letter to his sister that 25 January 1834, as the Andromache prepared to leave for China. Charles wrote:

I go to this place [China waters], dear Emy, with a fixed determination to do all I can for my family and myself, and to do for the public, not a whit more than my barest duty.

When I was at Demerara the governor [Sir Benjamin D’Urban] very frequently did me the favour to send me papers and memorandums to report upon, wholly unconnected with my own duties [as Protector of Slaves]. These trifling avocations commonly kept me out of my bed until three o’clock in the morning. I was called home by the government, because I was thought to be a person it would be well to consult in a most momentous public question [the abolition of slavery in British colonies),7 and after a profusion of fair words, I am led to understand, it I do not choose to go to China as Master Attendant in a salary acknowledgedly inadequate, I am to expect their displeasure.

I feel all this to be a humiliation, and a very sore one too, but I shall take very good care, that no sense of that description shall deaden the ardour of my own efforts in my own behalf. Neither am I without the conviction, that it will be very proper to wear a mask of good humor, or at least of indifference out of doors.

This last stroke has not been without its advantages. It has given me the true touch of bitterness and real selfishness, without which there is no success in this world. With the wisdom I have acquired now, I don’t despair dear Emy of some day dazzling your senses with the full grown glory of a groom of the Bedchamber (like Lord Napier].

My dearest little ones mend. Harriet pretty rapidly, but not so Hughie. He is better certainly, but it is only a very little better, and his cough is still frightful. Harriet has written you a note (I guiding her hand) and I declare to you every word is her own, just as it came from that queer little mint of a brain.

[Captainj Chads is very good natured, and I am sure he will do whatever he can to make us comfortable, but I shall endeavour to give him as little trouble as possible, not by the smallness or moderation of my wants, but by helping myself as much as I can, in strict conformity to my new principle of action – Aide toi, Dieu t’aidera [Cod helps those who help themselves].

The cabin is wretchedly situated enough, and as small as your faculties of smallness can well enable you to conceive, but seeing that I am only the Master Attendant, and that my Emperor [Napier] is going out with His Empress and two of his Imperial family, to my other Emperor in China, I suppose I am the most magnificently lodged of Masters Attendant.

Poor Clara congratulates herself that she did not spend all my Master Attendantial salary for a whole year in millinery travails for reason good there is to believe that we shall be drowned in our own cabin on the way out. Never mind, my turn of the wheel is down just now, but it will revolve, and I shall be up again some day.

It becomes necessary to ask now why Charles Elliot, a post captain in the Royal Navy of six years standing, and with three years political and administrative experience on an issue of moment, had accepted a job with so little apparent appeal. First, when he accepted it, he did not realise what was being offered. He wrote later, I was informed by the President of the Board of Control a few days before I left England that circumstances had prevented him from recommending me to His Majesty as one of the Superintendents.’8 But even then, he did not fully appreciate his sit...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Maps

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Authors’ Note

- Prologue

- 1. Whenever There is a Breeze (1801–34)

- 2. By Warship to China (1834)

- 3. Into the Tiger’s Mouth (1834)

- 4. Climbing the Ladder (1834–6)

- 5. The Opium Trade (1836–7)

- 6. Some Gross Insult (1838–9)

- 7. Elliot’s ‘Troublesome Friend’ (1839)

- 8. All Engineered by Elliot (1839)

- 9. Charles Elliot Alone (1839–40)

- 10. Looking Westwards (1840)

- 11. Two Such Imbeciles (1840)

- 12. The Road to Gloary (1841)

- 13. Whimsical as a Shuttlecock (1841)

- 14. Whipping off the Fox-Hounds (1841)

- 15. Wrecked Ashore (1841)

- 16. The Web of Calumny (1841–43)

- 17. Elliot, Where is he? (1843)

- 18. Exiled to St Helena (1843–75)

- 19. Epilogue

- Notes

- Genealogies

- Biographies

- Bibliography

- Chronology of Family Letters from Charles and Clara Elliot

- Index