eBook - ePub

Tourism, Heritage and National Culture in Java

Dilemmas of a Local Community

- 284 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Based on anthropological fieldwork in the 1990s, this book provides an ethnographic perspective in its examination of the politics and policies of cultural tourism as they were played out under the Indonesian New Order regime. The successful New Order tourism policy ensured that tourism development both contributed to, and benefited from, increasing economic prosperity and a long stretch of political stability. However, that success has come at a price; the policy to encourage mainly 'high-quality' tourism revolved around carefully constructed and controlled tourist experiences that have led to local inequalities. The failure of this policy is analysed in a detailed case study of the city of Yogyakarta.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Tourism, Heritage and National Culture in Java by Heidi Dahles in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Ethnic Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

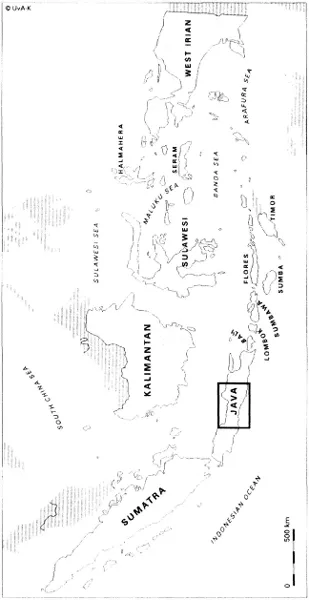

Map 1: Indonesia

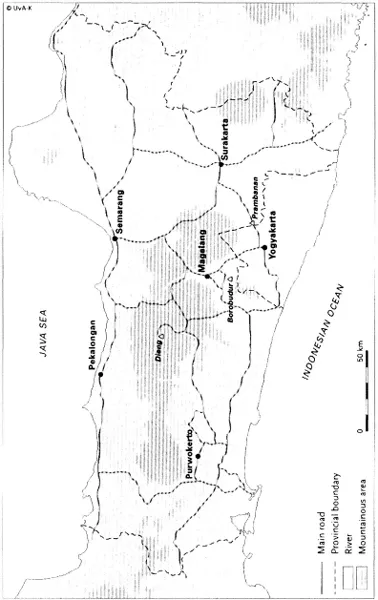

Map 2: Central Java and Yogyakarta's Special Province

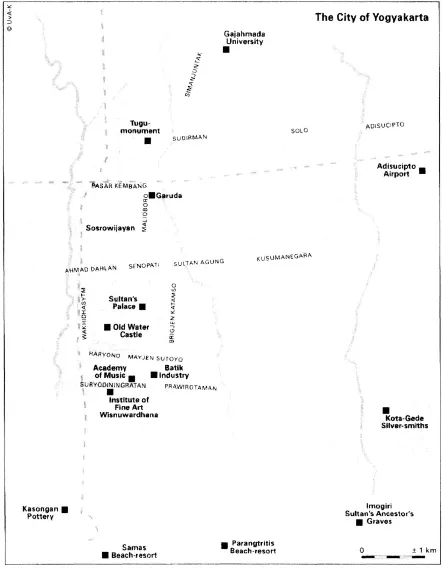

Map 3: Citymap of Yogyakarta

CHAPTER 1

TOURISM, POLITICS AND THE PARADOX OF CULTURE

CULTURAL TOURISM POLICY IN INDONESIA UNDER THE NEW ORDER GOVERNMENT

INTRODUCTION

In 1992 the first International Conference on Cultural Tourism in Indonesia was held in Yogyakarta, a middle-sized town ‘in the heart of central Java,’ as tourist guide books usually extol this place. On the surface the focus of the conference — cultural tourism — reflected changes in the advanced economies leading towards the formation of a consumer society in which the consumption of culture has become a major asset of economic growth in general and of tourism development in particular (Richards 1996:3–4). However, the hospitality offered to the conference and its delegates by the Indonesian government revealed a hidden agenda. The conference was organized and sponsored by the Ministry of Tourism, Post, and Telecommunications, UNESCO and the United Nations Development Project (UNDP) and supported by the World Tourism Organization (WTO), the Pacific Association of Travel Agencies (PATA) and others. This conference was attended by almost 400 delegates, a quarter of whom came from outside Indonesia. After two days of plenary presentations discussing subjects like tourism and cultural heritage, religious belief systems, the role of women, village tourism and tourism marketing, the organizing committee, chaired by Joop Avé (then Director-General of Tourism), launched the ‘Yogyakarta Declaration on National Cultures and Universal Tourism’ which was signed by the delegates. This declaration — the complete text of which is presented in Appendix 1 — has been strongly grafted onto the struggle for national unity that characterized Indonesia — and especially the New Order government of former President Suharto — since independence. The motto ‘Unity in Diversity,’ which was the major point of reference of many a distinguished speaker, was closely intertwined with the principles designed for global cultural tourism developments as outlined in the Declaration.

What we wish to encourage is the richness and diversity of the many cultures, and to inquire how the tools and technology that makes globalization possible can not only preserve and protect the cultures they make accessible but much more than this, to rather encourage a cultural renaissance, a renewal and an enriching of those cultures. We are not seeking uniformity among mankind, we are encouraging Bhinneka Tunggal Ika — Unity in Diversity,

writes Joop Avé in the Introduction to the Conference Proceedings (Wiendu Nuryanti 1993:xi). What may be regarded either as a mode to propel Indonesia into the transnational bodies that promote cultural tourism, or as the empty rhetoric of Indonesian state ideology, actually revealed the political programme which lay at the basis of the New Order's espousal of cultural tourism. Under the New Order cultural and tourism policies merged into a political programme. A state ideology celebrating cultural diversity, based on the pancasila, i.e. literally ‘five pillars,’ addresses the problem of national culture and supports the lucrative tourism industry (Kipp 1993:105). The New Order's catchphrase became kelestarian kebudayaan nasional, i.e. the preservation of national culture (Kipp 1993:113). What is at stake here is the impact of tourism not on culture — the anthropological concept defining the human condition of forming meaningful arrangements of co-habitation — but on national cultures, i.e. territorially and politically defined cultural entities. In his speech delivered at the opening of the Yogyakarta conference, then Minister of Education and Culture, Fuad Hassan, expressed his fear about cultural loss that may emanate from culture contact through ‘global tourism.’ Therefore he pleaded for ‘cultural awareness and cultural resilience’ to counteract the homogenization of culture. The appeal made by Fuad Hassan and the organizers to respect national cultures and to protect, preserve, and revitalize them for the purpose of cultural tourism development, and to enhance the awareness of and educate people for cultural tourism, reflects the New Order government's strategic use of cultural tourism development.

As an archipelagic nation consisting of more than 17,000 islands that extends over more than 5,000 kilometres from east to west and comprising over three hundred ethnic groups and a multitude of religions, Indonesia faces the challenge of building a shared national consciousness and identity. How fragile a construction this nation is, has now been pitilessly revealed in the political upheaval and the ethnic and religious conflicts that followed the economic crisis which broke out in 1997. The New Order government attempted both to control ethnicity and to use it. Paradoxically while ethnic and regional secession recurrently threatens national unity, indigenous cultures provide a repository of traditions and symbols that the political leaders and the national elite can use to forge national identity and foster a sense of community (Kipp 1993:105). Constructing nationalist ideals, a nationalist sense of history, and a transcendental loyalty to the nation have been goals of both the Old Order and New Order governments in their attempts to come to terms with ethnic diversity. Not only does Indonesia consist of very many different cultures and languages, there is also a distinct imbalance between these groups. The Javanese constitute two-thirds of the population, and they predominate in the leadership elite that flocks together in the economic centre of the country which is not Java as a whole but specifically Jakarta. The capital city enjoys a disproportionate share of the county's wealth. The state policies encourage traditional cultures partly to mask these imbalances. One way the Indonesian government strives to instil a broader sense of national unity is by championing tourism, in particular cultural tourism (Adams 1997:156).

The political programme behind tourism development was envisioned by the Indonesian leaders as early as 1969, when the contribution of the tourism sector to nation-building was defined in terms of a source of foreign revenue, a way of enhancing Indonesia's celebrity on the international stage, and a strategy for fostering domestic brotherhood (Adams 1997:157). In the early 1980s, facing declining oil revenues, the Indonesian economic policy was directed towards the expansion of non-oil sectors. Deregulatory measures were intended to facilitate private sector activities, particularly in the export sector (Booth 1990). Exports were the key to earning the foreign revenues to support the New Order's modernization projects. Tourism was embraced as a vehicle to contribute to economic development in terms of measurable growth. The high priority given to tourism in national development policy generated a rapid growth in tourist arrivals and in earnings from tourism, the latter a major source of foreign exchange. International and domestic tourism has grown considerably since the 1980s. The number of foreign visitors increased by more than 200 per cent between 1988 and 1995, and the income from foreign tourism more than doubled between 1990 and 1994. Before the crisis hit Indonesia, the government estimated that in the year 2000 about 6.5 million foreign tourists would visit Indonesia, yielding US$ 9 billion of foreign exchange earnings. Growth scenarios for the turn of the century anticipated visitor arrivals to double and income from foreign tourism to triple (Parapak 1995). In the wake of the crisis official sources state a decline of about 30 per cent of international arrivals and 60 per cent of revenues from tourism in 1998 (KOMPAS 31–03–1999).

In this book, the role of the Indonesian state, and especially of the New Order government, in the development of cultural tourism and its impact on tourism practices at the provincial level will be of central concern. This book has been inspired by Linda Richter's point that ‘tourism is a highly political phenomenon’ (Richter 1989:2) and that countries — especially in the developing world — see in tourism a means of enhancing their economic growth and their political legitimacy, the latter conveyed by the high number of tourist arrivals (Richter 1989:5–6). With a few exceptions, scholars have failed to consider tourism in terms of the political strategies deployed by power holders. ‘Such needs are not publicly articulated like economic objectives are, but that makes them no less salient in policy development, implementation, and evaluation’ (Richter 1989:19). The a-political approach to tourism in academic discourse reflects the fact that tourists are seldom aware of the agency of the state in structuring the images and the experiences of travel (Wai-Teng Leong 1997). Nevertheless, the state is a major actor in tourism, not simply by providing the infrastructure for services but also by creating the images and symbolic representations that shape tourist experiences. In their introduction to one of the first volumes addressing tourism issues in Southeast Asia, the editors pointed out that

We need more data on the relations between national identity, political image building and tourism (…). These national arenas of representation are also the focus for conflicts over identity and the contesting by various social groups of particular constructions of ‘national culture. (…) The whole field of policy-making with regard to tourism is a virtual terra incognita (Hitchcock, King & Parnwell 1993:29).

As will be argued in this book, the New Order government strategically promoted the expansion of (cultural) tourism to implement its political agenda. This book looks back on thirty years of tourism policy under former President Suharto who identified tourism as a major asset in his policy of economic growth and development. On his agenda for tourism development the following points predominated:

1.The increase in the Gross National Product through tourism revenues, especially foreign revenues.

2.The polishing of the image of Indonesia to attain international esteem and status as an economically prosperous, politically stable, and culturally sophisticated country before a world audience through the advancement of international tourism and participation in a global market.

3. The domestication of its ethnic minorities and control of cultural diversity through the commercial exploitation of selected (so-called ‘peak’) ethnic cultures as tourist objects.

4.The strengthening of national unity, pancasila state ideology and other basic values of the New Order government through domestic tourism.

These four interdependent strategies resulted in carefully constructed, staged, and controlled tourist objects and destinations operated by a Jakarta-based tourism industry under the watchful eye of the Ministry of Tourism, Post and Telecommunications. As Indonesian provincial boundaries are an often overlooked factor in shaping the discourse of tourism development and promotion (Adams 1997:156), this book will focus in particular on the way in which provincial governments and local actors in the tourism industry cope with, give shape to, and counteract Jakarta-initiated tourism policy guidelines. This focus answers the call for a local-level approach to tourism issues. As Hitchcock, King, and Parnwell (1993) point out local perspectives on tourism and leisure have been very much neglected, largely eclipsed by the representations of those who promote and sell the tourist product. Local people create niches for themselves to benefit directly or indirectly from the state's incapacity to organize tourism according to its own plans.

Crucial elements are the tour agents, guides, and leaders who act as social and cultural brokers between tourists and hosts. Yet again, we do not know much about how these intermediaries convey information, organize and conduct encounters, and portray local cultures and scenes. This kind of research requires local-level anthropological fieldwork (ibid:29).

The focus of this book is the Special Province of Yogyakarta, the host of the first and then a number of subsequent conferences on cultural tourism and the gateway to the two UNESCO-designated World Heritage sites in Indonesia, the temple complexes of Prambanan and Borobudur. Contrary to popular wisdom, both temple complexes are partly (Prambanan) or completely (Borobudur) located outside the Special Province of Yogyakarta in the neighbouring province of Central Java (Wall 1997b). Despite this, as one of the plenary speakers of the 1992 conference pointed out, the region of Yogyakarta is a ‘demonstration of the ‘unity-in-diversity’ guiding theme of Indonesia’ (Gertler 1993:15). Yogyakarta has played a prominent role in the political history of Indonesia. Many of the city's current tourist resources are derived from its royal and military past (Timothy & Wall 1995). As both the vanguard of traditional Javanese culture and testing ground of nationalist forces, Yogyakarta is a place where heritage and tourism have become closely intertwined to establish a highly challenging arena in which to study processes of inventing, (re-)producing and (re-)presenting cultural identity. Images of Yogyakarta form an expression of the tensions between the global, national, and ethnic interests. This study aims to reveal the struggle between processes of globalization introduced through the transnationally organized tourism industry and the influx of large numbers of international tourists, Tndonesianization' through Jakarta-led policies and Jakarta-based project developers, and ‘indigenization’ through local practices and performances of the ‘tourist product.’ To analyse the partly converging and partly conflicting forces at work, the following questions will be addressed:

1.How did the New Order government attempt to accomplish the objectives of economic development, national unity, and cultural diversity through tourism and how does it deal with the potentially problematic situation created by ethnic revival through cultural tourism?

2.To what extent did the pancasila state ideology influence the social construction of the ‘national’ cultural heritage and how did Tndonesian-ness' relate to ‘Javaneseness’ in local tourism practice?

3.To what extent did local practices and performances representing local cultural heritage converge or conflict with government-orchestrated pancasila tourism? Through what institutions has pancasila tourism been either maintained or undermined?

4.What are the mechanisms of ‘authentication’ by which the New Order government attempted to control tourist discourses?

5.To what extent did ‘uncontrolled’ local discourses form a threat to government-orchestrated pancasila tourism?

Each of these questions will be addressed in separate chapters in this book.

CULTURAL TOURISM AND THE ‘PARADOX PARADIGM’

The organizers of the Yogyakarta conference on cultural tourism were well aware of the global impact of tourism on culture. Hence the title of the conference: ‘Universal Tourism — Enriching or Degrading Culture?’ Many contributions discussed the threat of cultural loss and the emergence of a homogeneous global culture in the wake of increasing intern...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Map 1: Indonaesia

- Map 2: Central Java and Yogyakarta's Special Province

- Map 3: Citymap of Yogyakarta

- 1 Tourism, Politics and the Paradox of Culture

- 2 The Politics of Tourism in Indonesia

- 3 Pancasila Tourism in the Heart of Central Java

- 4 Prominent Players in Yogyakarta's Tourism Arena

- 5 The Politics of Guiding

- 6 Blurring the Boundaries

- 7 Local Identity and National Culture

- 8 Epilogue

- Appendix 1 The Yogyakarta Declaration on National Cultures and Universal Tourism

- Appendix 2 Number of Foreign Visitors to Indonesia and Revenues 1969–96

- Appendix 3 Number of Visitors (Foreign and Domestic) to Yogyakarta, 1973–95

- Appendix 4 Number of Visitors (Foreign and Domestic) to the Core Attraction Sites of Yogyakarta Kraton, Prambanan and Borobudur 1989–95

- Glossary

- References