eBook - ePub

J.R. McCulloch

A Study in Classical Economics

D. P. O'Brien

This is a test

Share book

- 456 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

J.R. McCulloch

A Study in Classical Economics

D. P. O'Brien

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This is one of the first complete surveys of McCulloch's work, and it shows his thought to have been far more complex and comprehensive than has previously been realized.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is J.R. McCulloch an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access J.R. McCulloch by D. P. O'Brien in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business generale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

III

McCulloch and the Press

During a long and active career as a writer on economic theory and policy John Ramsay McCulloch was connected with a number of publications. These connections were important in three ways; firstly they provided him with outlets to expound his views; secondly, they supplied him with an income; and thirdly, they affected his relationships with those in authority.

McCulloch’s main periodical writings are to be found in the Scotsman and the Edinburgh Review, and his activities in connection with those two publications will be examined in detail.

1. THE ‘SCOTSMAN’

In 1817, two opponents of the then Edinburgh establishment, William Ritchie, a solicitor, and Charles MacLaren, a civil servant, founded the Scotsman. The founders were not Whigs – indeed Ritchie wrote: ‘that paper was not commenced by the Whigs; it was not supported by their money; and some of them were very tardy in becoming subscribers’.23 But newspaper opposition of any sort to the Tory administration was both unusual and dangerous.24 McCulloch himself was very conscious of this. Some years later he wrote to Poulett Thomson: ‘At the time the Scotsman commenced there was not a single liberal Newspaper in Scotland; every one that had previously been tried had failed, their Editors being sent to ruminate over their fool-hardiness in Jail or in New Holland . . . the Dundases rode rough shod over Scotland; . . .25 the Scotsman made its way in defiance of every obstacle and produced the most extraordinary change in the public opinion of Edinburgh and of Scotland generally, that I am bold to say, ever was produced by any periodical in any age or Country . . . Lord Jeffrey, the present Lord Advocate, the Speaker, and the whole people of Scotland26 knows that all I have stated is true to the letter.’27

McCulloch joined the paper shortly after its commencement.28 He was for a time editor of the paper, and the accepted version of the story is that he was editor for the years 1818 and 1819,29 being succeeded by MacLaren. McCulloch himself took a different view. He told Poulett Thomson, for instance, that he was editor for ‘nearly the first five years’.30 It seems fairly clear that he was telling the truth, on three grounds. Firstly there is the evidence of what was recognized in Edinburgh at the time, secondly that of the contributions to the paper, and thirdly that of the payments received.

Firstly, it seems clear that he was recognized as editor up to 1821 at least. In 1823 when the Scotsman was involved in a libel case with political overtones,31 McCulloch was sued as having been editor in 1821, the time of the libel; and John Hope the Solicitor-General, told Lord Melville that he understood from Francis Jeffrey that McCulloch had been ‘the principal writer in . . . and . . . the responsible Editor of, the Scotsman newspaper for the first four or five years after its institution’.32

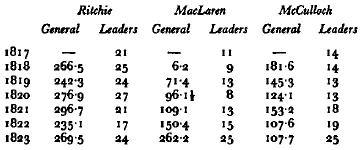

Secondly, it was not until the third year of MacLaren’s supposed editorship that he equalled McCulloch as a general contributor, and it was not until 1823 that he wrote as many leading articles as McCulloch. The figures are as follows:33

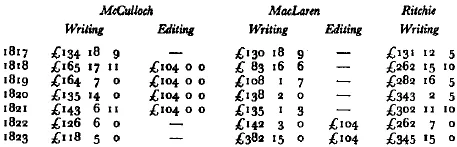

Thirdly, McCulloch received a payment for editing, which continued until 1821.34 The general arrangement was that he received £2 per paper for editing, but that payment for writing was arrived at by dividing up the net revenue of the paper in proportion to the contributions of the writers.35 The total payments and editorial allowance were:

The only year up to 1821 about which there can be any doubt then is 1817. Here it seems reasonable to deduce from a statement by Ritchie that McCulloch became editor half-way through 1817.36 From 1817 till 1821 it seems clear he was editor; and even after he ceased to be editor he was consulted on matters of policy.37

But although editor, he does not seem to have been a proprietor. He raised £1,000 on the security of his estate, Auchengool, in 181738 but does not seem to have invested it in the paper – which was unfortunate because it was a profitable concern.39 But late in 1822 he offered to lend the proprietors £1,000 prior to the paper’s becoming a twice-weekly40 publication the following year.41

But although never a proprietor his importance during the first formative years is undeniable. MacLaren’s reasons for underestimating McCulloch’s role are, however, not too difficult to find,42 for McCulloch’s relationship with Ritchie and MacLaren does not appear to have been very happy.

Most obviously, there was the dispute, detailed below, over Aiton’s case. Secondly, McCulloch clearly felt that his essays were not being accorded their true worth since early in 1824 MacLaren felt constrained to write to him that: ‘Mr Ritchie concurs with me entirely in allowing that your essays are of more value intrinsically than the general run of articles got up by him and me on the spur of the occasion whether we are prepared or not. But the latter sort of articles are indispensable . . . though their absolute value is less, their utility in what regards the success of the paper may sometimes be greater than that of the other.’43 It was precisely those (theoretical) articles which seemed most valuable to McCulloch that the others wished to avoid: ‘We need scarcely say that it would be desirable to have the Essays as much as possible on emerging topics—the great object being the application of your peculiar science and extensive reading to legislative measures and questions of public interest as they arise.’44 But the differences were wider than this for Ritchie wrote a long letter to McCulloch45 emphasizing the risks incurred in founding the Scotsman both for his law practice and MacLaren’s civil service appointment. He argued that the two founders were then entitled to a reasonable return and that since it was they who were responsible to the proprietors who had financed the venture they must have ultimate control.46 Ritchie seems to have felt it necessary to defend himself and MacLaren and he told a friend that McCulloch had failed to write his share of short articles and, apparently to counter any over-estimation of McCulloch’s influence, stated that as McCulloch’s share of the leading articles increased the circulation fell. He wrote of himself and MacLaren in relation to McCulloch: ‘It will not be their fault, indeed, if he gives up writing for the Scotsman. It has been their study all along to act kindly and liberally towards him. They believe they have done so.’47 He went on to claim that he and MacLaren never lost any opportunity of praising McCulloch ‘although some persons have been exceedingly active in persuading the public that all the merit connected with the paper was his’.48

Be that as it may, McCulloch’s effect on the early years of the paper was considerable; and his association with it was personally significant for him. On the credit side, apart from the income it provided, it gave him an outlet for developing theoretical ideas and policy prescriptions, and a platform for defending himself against attack. On the debit side it involved him in the mêlée of Edinburgh politics and public abuse.

One interesting example of the Scotsman providing an outlet for his ideas is that of his views on absenteeism. In defence of his views expressed before the Committee on Ireland he stated that he had first published his views in the Scotsman,49 and that they had been copied into London and Dublin papers, and discussed and approved at the Political Economy Club by Parnell, Ricardo, Tooke, Mill, and Warburton. Publication in a newspaper provided, so he argued, a useful first way of airing one’s views so that they could be modified if necessary before publication in a less transient form.50 But his re-use of material published in the Scotsman in other forms, particularly the Edinburgh Review, was enough to occasion an attack by John Wilson51 who, as McCulloch’s arch-enemy in Edinburgh was concerned to discredit McCulloch as an economist and deprive him of his livelihood, by abusing McCulloch’s publishers and students alike as fools taken in by a man who constantly republished the same material. Wilson’s case was not very strong52 and in any case the practice itself was not particularly reprehensible, but Wilson had at last been forced (after the attempt to establish a Chair of Political Economy at Edinburgh on McCulloch’s behalf had been prevented on the grounds that the subject came within Wilson’s purview as Professor of Moral Philosophy) to prepare lectures on economics; it was thus that he made his detailed survey of McCulloch’s writings. He clearly felt a strong need to rid the field of his obvious rival as a ...