- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Applied Economics

About this book

Among the issues discussed in Applied Economics are world population growth and the economic factors governing international migration: issues that are as pertinent today as when the book was originally published.

The problems of defining and comparing industrial and general efficiency in different economies are also discussed, using comparative studies from the UK and USA. The opportunities for analysing the pattern of world trade and the reasons for the varying degrees of national dependence on external trade, as well as the concentration of world export in particular channels are also examined.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER I

STUDIES IN RE-ARMAMENT

1. GERMAN RE-ARMAMENT, 1932-8

GERMAN re-armament constituted one of the main factors in the political life of the world in the period 1933-9 ; moreover, both by its direct effects on the German economy and its indirect effects in setting the pace for re-armament elsewhere, it constituted one of the main economic factors. It is therefore with German re-armament that any study of the world’s preparation for the war of 1939-45 can most conveniently begin.

The story is essentially that of the expansion of Germany’s national income from the low levels of the Depression, and the diversion of the increment—or most of it—to military or closely related purposes. The first questions which arise, therefore, are : What was the size and composition of the German national income before re-armament began ? and : How did they change in the succeeding years ?

THE GERMAN NATIONAL INCOME

These questions are not easy to answer. The German national income during the war years, and for a few years before, has been thoroughly studied by the United States Strategic Bombing Survey, which has published its findings in a Special Paper entitled The Gross National Product of Germany, 1936-1944. For earlier years—and, indeed, for all years up to 1944—official estimates of the national income by the Statistisches Reichsamt are available ; but these estimates are extremely difficult to reconcile with the U.S.S.B.S. estimates—indeed, the authors of the latter state that “ Data for the items necessary to effect conceptual comparability are not available,” and relied mainly on other sources, notably some semi-official estimates by Dr. Grunig. Nevertheless, the Statistisches Reichsamt’s estimates must receive a little attention here, since it is desired to carry estimates back to earlier years, with which the Strategic Bombing Survey, and the special German sources from which it drew, did not deal.

For a number of years up to 1931, materials for an independent estimate of gross product exist. Dr. Marschak has estimated expenditure on consumption (in an article in the Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft, 1932). The same author’s work with Dr. Lederer on capital formation gives the necessary investment data, and the public accounts make it possible to estimate public exhaustive expenditure (i.e. public purchases of goods and services) on current account. Statistics of retail sales extend from the period to which these estimates refer to the years after 1936, for which the U.S.S.B.S. has assembled material—including a careful independent estimate of consumers’ expenditure. It is likely that these figures of retail sales give a fairly good clue to the proportionate changes in the value of goods and services taken up by consumers ; using them for this purpose, however, one finds a considerable discrepancy between the Marschak estimates for 1931 and the U.S.S.B.S. estimates for five years later, the explanation of which seems to be that the former omit a great deal of the indirect taxation which enters into consumers’ purchases, and which is fully included in the later figures. If this indirect taxation is added on to the components of the pre-1931 gross product mentioned above, one obtains an estimate of the German gross product which should be approximately comparable with the post-1936 estimates.

There is a further check on this. The chief peculiarity of the Statistisches Reichsamt’s estimates of national income referred to above is that they deliberately exclude certain goods and services bought by the public authorities for purposes which are regarded as essential to the maintenance of the national income as a whole—e.g., purchases for road-maintenance, general administration, fire-brigades, police, and (according to the official statement in the Reichsamt’s Sonderheft Nr. 24 of 1933) defence. Now, it is clear that the last item has never been omitted in tolo—since the late 1920’s, at least—but much has undoubtedly been omitted which is included according to British and United States practice, and which it is not possible to estimate by a study of budgetary data alone. Mr. Colin Clark (in The Conditions of Economic Progress) recognised the nature of the problem, but the corrections which he applied in order to make the German national income statistics accord with his own definition were certainly far too low.

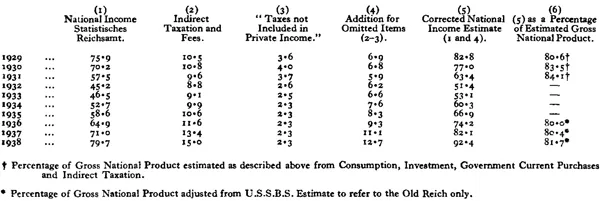

Fortunately, it is possible to arrive indirectly at the items which are omitted—they are simply the total of indirect taxes and fees to public authorities minus a curious item in the official German statistics which is misdescribed as “ taxes not entering into private income.” There are certain further adjustments to be made before the German official statistics conform to the British definition of national income (or to the United States definition of gross national product used by the U.S.S.B.S.) for some of which the basic data are lacking. The German official figures corrected for the omitted items of public expenditure might, however, be expected to vary over time approximately proportionately to gross national product. The comparison is made in Table I.

This table suggests that the estimate of gross product made, as described above, for the years 1929-31 may be rather low (assuming that the later ones, adjusted from the U.S.S.B.S. estimates, are correct). They also suggest, however, that the margin of difference is not very great—having regard to the roughness of the whole calculation. The authors of the U.S.S.B.S. Report on gross product used the uncorrected German official figures in a similar way as a check on their estimates of gross product from 1936 to 1944. They found that for every year except 1944 (for which only a very rough preliminary official figure is available) the Statistisches Reichsamt’s figure lay between 69 and 72 per cent. of theirs. There is reason to believe that this check would have broken down if they had tried to carry the comparison further back to years in which the deliberately omitted items of public expenditure constituted smaller proportions of the total than they did in the later years of intensive re-armament. The ratio of the official figure to the estimate of gross product arrived at above for the year 1929 is 74 per cent.—well outside the range obtained for the later years. The corrected official figure used here is, a priori, likely to afford a better check.

TABLE I.

German Official National Income Estimates, corrected for the Omitted Items of Public Expenditure, and compared with Estimates of the Gross National Product.

It seems, then, that the U.S.S.B.S. estimates of the German gross national product may, for the particular purpose of this chapter (which is broad economic analysis rather than exact measurement), be taken back to the years 1929-31. Various gaps are left, however, between those years and 1936. The gap in consumption data between 1931 and 1936 may be filled by interpolation with the help of retail sales statistics ; official data on net investment are available throughout the period, and estimates of depreciation, necessary to convert these into figures for gross investment, can easily be made with a relatively small margin of error. Governmental purchases of goods and services on current account—the most interesting item of all—is, however, not available from public accounts after 1932 (the publication of the budget having ceased with the Nazi party s accession to power) and estimates of them for 1933, 1934, and 1935 must therefore be very tentative—the course of total tax revenue affords some clue to the way in which they changed from year to year ; but only a slight one, for not only was taxation supplemented by borrowing, much of it secret, which was used to an unknown extent for other than the capital purposes included in the official statistics of net investment, but how much of the public authorities’ total financial resources were used for transfer payments between the years 1932 and 1936 is also a matter largely for conjecture.

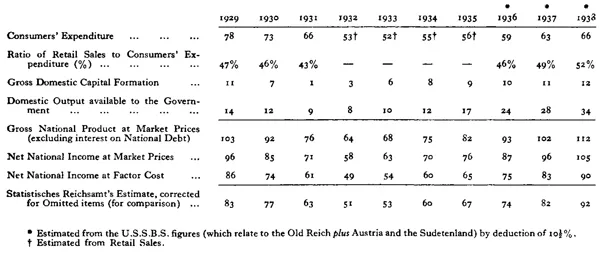

Nevertheless, for the general purposes of this discussion, a sufficiently clear statistical picture of the development of the German economy can be drawn for the whole period 1929-38, as is attempted in Table II. At the bottom of this table the net national income at market prices is shown (it is obtained by the deduction of estimated depreciation allowances) and this is then reduced to factor cost (i.e., to the aggregate prices of the factors of production used in producing the country’s net output) by the further deduction of estimated indirect taxation and fees. This figure should be very roughly comparable with the Statistisches Reichsamt’s estimate of national income, corrected as described above for the items of public expenditure which are deliberately omitted from it. It will be seen that the two series of figures do, in fact, show a fairly close correspondence over the period as a whole.

TABLE II.

Components of the German Gross National Product, 1929-38 (Old Reich only ; Milliard Rm.).

The outstanding feature of this table is, of course, the enormous growth of Government purchases of goods and services after 1932. Between that year and 1938 the net national income increased by 41 milliard Rm., of which no less than 25 milliard, or over 60 per cent., went to the Government—excluding that which went to publicly controlled capital formation. Private consumption took only 8 milliard, or under a fifth of the increase. It is not hard, therefore, to see the source of the great increase in German economic activity under the Nazis ; to an overwhelming extent it was the direct result of increased demand on the part of the public authorities. Recovery from the depression was effected, not by “ pump-priming,” but by a direct substitution of public for private demand. The situation changed, however, in the course of the years concerned. In the first two years of Nazi government increase in gross capital formation seems to have been at least as important as increase in public purchases of a non-investment nature in stimulating activity ; subsequently it played a much smaller part, both relatively and absolutely.

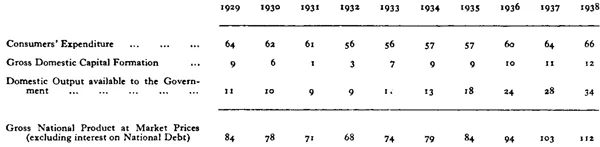

What the changes under discussion amounted to in real terms—i.e., if measured at constant prices—is roughly indicated in Table III. This suggests that the real national product of Germany fell by not far short of 20 per cent. in the course of the depression after 1929, regained its 1929 level by 1935 (as did that of the United Kingdom also), and by 1938 had risen some 33 per cent. above the 1929 peak. Consumption, however, both fell less and rose more slowly ; the decline from 1929 to 1932 or 1933 seems to have been only some 12 or 13 per cent. ; the 1929 level was, however, not surpassed until 1938. (It is perhaps worthy of note that the Reichskreditgesellschaft in 1939 declared that real consumption in the previous year had passed the 1929 level.) The population had, meanwhile, increased by about 5 per cent., so that the slight excess of total consumption in 1938 above the 1929 level, which these figures indicate, can hardly have meant any appreciable net increase in real consumption per head. The one-third increase of the German national product of 1938 above the pre-Nazi peak level was made up mainly of the State’s share (which had trebled), and, as for the remainder, of a one-third increase in gross capital formation. The consumer had no share in the enjoyment of it, though he had regained the ground previously lost in the depression after 1929. The increase in output was, of course, largely associated with an increase in employment and a diminution of unemployment. The latter had been very heavy, exceeding 51/2 million in 1932 ; by 1936 it was down to a level of 11/2 million which, having regard to the size of Germany’s occupied population, appears at first sight to indicate a nearer approach to full employment than was attained in the United Kingdom in any year of the pre-war decade. The improvement is to some extent illusory, since, after 1933, those in labour camps were excluded from the statistics of unemployment ; and the expansion of the armed forces in any case created a situation which it is hard to compare with that in the United Kingdom. Nevertheless, the great bulk of those formerly unemployed had found normal employment by 1936, by which year, also, total employment in mining and industry seems (from the rather inadequate sample data available) to have regained the 1929 level, i.e., to have recovered from the 40 per cent. fall which had taken place (according to these same data) in the depression. It is noteworthy that the Institut für Konjunkturforschung Index of Industrial Production fell by no less than 42 per cent. between 1929 and 1932—a piece of evidence which helps to render this great fall in employment more credible—and that, by 1936, it stood some 6 per cent. above the 1929 level ; an increase which, again, accords fairly well with the regaining of the 1929 employment level and a moderate rate of technical progress, or with the 12 per cent. increase in total real income.

TABLE III.

Components of the German Gross National Product, 1929-38, measured at the Prices of 1939 (Old Reich only ; Milliard Rm.).

After 1936, however—when the rate of unemployment in Germany was already down to a level which would be associated with a pre-war boom year in the United Kingdom—the index of industrial production rose in two years by a further 19 per cent., and the real national income as a whole rose by about the same proportion. This change was accompanied by a 17 per cent. increase in the numbers in industrial employment and a 19 per cent. increase in the total number of hours worked in industry. The number of unemployed in the Old Reich at the same time decreased to less than half a million—a rate of unemployment similar to that prevailing in the United Kingdom in 1946, The total population to which the number of unemployed should be related is somewhat uncertain, but it seems that most, though not all, of the increase in employment and national product between 1936 and 1938 is to be attributed to the further absorption of unemployed workers into employment—to a reduction of the unemployment rate from something like the United Kingdom’s 1937 boom level to its 1946 level. There must, however, have been some absorption of workers into industry from other occupations, or a net increase of the total labour-force. Probably both of these things occurred.

The State was thus taking a constantly increasing share of the national gross product from 1932 (when it took an eighth) to 1938 (when it took nearly 30 per cent. of it). How did it use this large and increasing share of the national resources ? For 1932 the Reich budget supplies a fairly adequate answer to this question ; after 1936 the U.S.S.B.S. has broken up the total to some extent. It is possible to obtain a reasonably good estimate of the salaries of administrative personnel for all the years concerned, and it is, at all events, clear that this item roughly doubled between 1932 and 1937 or 1938—a reflection both of the growth of state planning in Germany and of the duplication of administrative organs which was a feature of the Nazi system. Deducting these expenditures on administrative salaries from total public purchases of goods and services, one is left with figures which must bear a fairly close relation to those for expenditure connected with re-armament. A rough estimate of the latter may, indeed, be obtained by taking for each year the excess of non-salary expenditure in it over the corresponding expenditure in 1932, and adding the armament expenditure of the last-mentioned year—which is officially (though perhaps rather misleadingly) given as about 1 milliard Reichsmarks.

...Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- International Economics

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Preface

- Contents

- I. Studies in Re-Armament

- II. Economic War Efforts—A Comparison

- III. Wartime Inflation

- IV. World Population Studies

- V. Industrial Efficiency and National Advantages

- VI. Studies of International Trade

- VII. The Economic Impact of Atomic Energy

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Applied Economics by A. J. Brown in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.