- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

J A Comenius and the Concept of Universal Education

About this book

Originally published in 1966, this volume reappraises the educational philosophy of Comenius. Until recently the attention given to Comenius and his work concentrated on a narrow interpretation of his pedagogy which played down his pansophic theory. In the second half of the nineteenth century Germany led the way in pedagogical study and Comenius was widely accepted as having laid the foundations of a science of education. The emergence of education as an academic subject in England and the USA led to a considerable interest in the history of educational ideas and Comenius' work.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access J A Comenius and the Concept of Universal Education by John Edward Sadler in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education GeneralCHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

SINCE 1829 when František Palacký drew the attention of his countrymen to the greatness of John Amos Comenius (Komenský) numerous biographies have been written and it would be superfluous to add to their number. The most detailed account in Czech is that of J. V. Novák and Josef Hendrich in 1932. There is an excellent study in French by Anna Heyberger in 1928 but the best English biography is entitled That Incomparable Moravian by Matthew Spinka of Chicago in 1934. There is a wealth of material in the collections of Correspondence of A. Patera in 1892 and of Jan Kvačala in 1897 and 1902 and also in the papers of Samuel Hartlib used by G. H. Turnbull in 1947. Comenius wrote an autobiographical defence against the attacks of one Samuel Maresius in 1669 (Continuatio admonitionis) parts of which have been translated into English by R. F. Young in 1932 (Comenius in England). Following the Prague Conference of 1957 on the 300th anniversary of the publication of the Collected Works of Comenius (Opera Didactica Omnia) a popular account was written by František Kožík and this has been translated into English (Sorrowful and Heroic Life of John Amos Comenius) in 1958 and two novels in Czech have aroused much interest in his story.1 Nevertheless it is necessary to give a survey of the biographical, historical and bibliographical background to the development of ideas concerning universal education.

BIOGRAPHICAL

A strong sense of vocation is the key to the life of Comenius in that it lifted him above circumstances, above his critics, even above his own defects and limitations. An essentially humble man, his lips had been touched with a live coal from the altar and this gave him a consciousness of power which would otherwise have indicated presumption. Thus it was in keeping that he should compare himself to Moses – ‘since my wish, so like to that of Moses (of desiring that all people should be prophets) became known, I have found so many opponents, that I cannot keep silent’2 and the comparison might well form a basis for an analysis of his life.

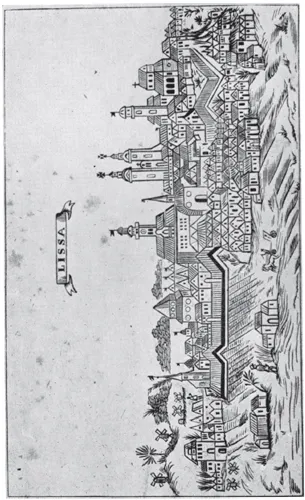

John Comenius was born on March 28, 1592, though, like Moses, in obscurity. There were three girls and himself in the family of Martin and Anna Komenský and they came from the village of Komna in South East Moravia. A few miles away is the town of Uherský Brod where the father became a respected member of the religious body known as the Unity of Brethren and where Comenius grew up. In the seventeenth century it was a place of some importance though it had declined since the Middle Ages. The print of 17043 shows four gates in the wall that surrounded it but it was evidently not impregnable for one sector is on fire and this was not the first time for it was partially destroyed in 1683. Some distance away and nearer to the pine and birch-clad slopes of the White Carpathians is the smaller town of Nivnice, confidently claimed by many as the actual birth-place. The mill is pointed out, beside a quietly-flowing stream, which local inhabitants are convinced marks the site of his original home and where he spent some of his childhood years.

At the age of twelve John Comenius lost father, mother and two sisters, probably from pestilence. They were buried in the cemetery of Uherský Brod4 and an uneasy period followed for the orphan. For a short time he was at Strážnice nearer to the Hungarian border in the charge of an improvident aunt and unhappy at school. Then he came back until, at the age of sixteen, he was sent by his Church to the Grammar School of Přerov, and it was here that his fortune changed. He proved to be an apt scholar and was accepted into the household of the Rector, Bishop Lanecký, as an acolyte in training for the ministry. From the bishop he received the name of Amos, meaning Loving, and was accepted almost as a son. Through the Bishop he was brought to the favourable notice of the leading nobleman protector of the Brethren, Charles Žerotín, and thus a few days after his nineteenth birthday he matriculated at the Calvinist Academy of Herborn in Nassau. In his studies he had an intense sense of purpose and excellent teachers and, in a remarkably short time, laid the foundations of a scholarship which, if not profound, was adequate for his needs. After a brief visit to Amsterdam he went for a year to the University of Heidelberg where he received inspiration from his teachers and interest from the wedding of the young Elector Palatine, Frederick, to Princess Elizabeth of England.

His studies finished, he returned to Přerov as a teacher until, at the age of twenty-four, he was ordained as a Minister of the Brethren at a Synod held at Zeravice in Moravia. For the next two years he acted as assistant to Bishop Lanecký and his first pastoral appointment was to the church at Fulnek in Northern Moravia. He was held in high esteem and had a very considerable responsibility with a mixed congregation of Czechs and Germans and the direction of a school. The Church buildings were considerable as is obvious from the reconstruction work now being carried out by Professor Menel. The minister’s house had accommodation for servants and young men preparing for the service of the Church and when he went to Fulnek Comenius took with him as wife the stepdaughter of the Burgomaster of Přerov, Magdalena Vizovská. Within the year he was comfortably settled in, a child was born, he had a library and a reasonable expectation of useful service. He might have considered himself a prince in Egypt.

Almost immediately there fell upon him the plagues of Pharaoh, Pharaoh being in this case the Emperor Ferdinand II and the plagues the Spanish soldiery who over-ran the land and the pestilence that followed in their wake. For seven years Comenius was a refugee in his own land sheltering wherever noblemen were able to afford him shelter. His young wife, being just delivered of a second child, died of the pestilence and with her the babies. He fled, perhaps to Třebíč where he was with a Pastor Paul Cyrillus, then to Brandýs in the most beautiful valley of the Orlice River (now called Komenský Valley). In this place Charles Žerotín had power to give him safety for a time but the most secure refuge was in the remote fastnesses of the Giant Mountains. At the age of thirty-two he married again, this time to Dorothy, daughter of Pastor Cyrillus, and maintained an uneasy life at Třemešna (North-east of Dvůr Králové) on the estates of George Sadovský of Sloupno.

These seven years were without doubt filled with anxiety and pain. He was constantly aware of the destruction of his land and the persecution of his Church. He had to live in secret hiding-places. Matthew Spinka speaks of his ‘formidable exterior’ in the face of his personal tragedies but this seems less than just. The ‘little book’ which he sent to his wife left behind in Fulnek may seem to us stiff and theological but the letter which accompanied it was a cry from the heart – ‘I am forced to leave you and cannot be by your side and I know the sorrow and distress in your heart of which I am not exempt’.5 As a minister he had to keep faith and hope alive in others and for this purpose the words of Scripture came to him most naturally and there is every indication that he was helpful in his ministrations to distraught women such as his own mother-in-law, Madam Cyrillová, to whom he sent a tract : ‘The Name of the Lord is a high Tower’. It was from a young girl of sixteen, Christina Poniatowska, driven crazy by terror that he himself derived a support for his faith through her prophecies of ultimate deliverance. Surely God, who had opened up a way through the Red Sea, could deliver his faithful Church in Bohemia.

It was, therefore, in confident hope of eventual salvation that in 1628 Comenius and a considerable band of the Brethren crossed the mountains and found a temporary home for themselves at Leszno in Poland. There they joined the descendants of an earlier band of exiles who had fled in the previous century and found relative security under the local lord, Rafael Leszczyński. It was, however, to be their home intermittently for twenty-eight years and for Comenius it was a wilderness experience. However sanguine their hopes the exiles had to adjust themselves to their Polish neighbours. Leszno had a school, which had become a gymnasium in 1624, in which Comenius was soon involved and, when the printing press from Kralice was set up, it became the publishing centre for the Brethren. In all the activities of his Church Comenius took an active part especially after he became Secretary. He was an indefatigable correspondent and he was always ready to defend or advance the cause of the Brethren with his pen. In addition, he had the cares of his aged parents-in-law and a young child and did what he could to fulfil the duties of citizenship when special need arose as, for instance, when pestilence threatened the city.6

2. Leszno

Of all the dark years experienced by the Leszno community none was blacker than 1632. In that year Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, whom they had thought invincible if not immortal, was killed at Lützen; Frederick of the Palatinate, the ill-fated Winter King of Bohemia, from whom so many summers had been expected, died a few days afterwards a wanderer and an outcast. Earlier in the year Landgraf Moritz of Hesse-Cassel, perhaps the most enlightened of the German Protestant princes, had died. Comenius wrote a funeral poem bewailing these losses – the removing of the very pillars of the Protestant cause7. How could he continue to believe in prophecy when the foretellings of Christina Poniatowska and Christopher Kotter were thus proved false ? It was not the first crisis of faith but Comenius turned increasingly to a concept which he believed would make possible the reform of all men. This he called Pansophy through which ‘men, seeing in a clear light the ends of all things, and the means to those ends, and the correct use of those means, might be able to direct all that they have to good ends’.8 Henceforth to realize this concept universally became the burning passion of his life and the vocation to which he dedicated himself. First he had to persuade his Church for, without their support, he could not go forward and one of the Brethren – a Polish noble, named Jerome Broniewski – feared that there was a danger ‘in the admixture of divine things with human’. Might Pansophy be, not the Promised Land, but the Golden Calf ? However, after two enquiries by the Bishops and then the whole body of the clergy Comenius was given full support to go on.

For fifteen years from the age of forty-nine to sixty-four Comenius tried in one way or another, in one place or another to spy out the land to which he believed mankind was destined. His wanderings took him far from his native land or his adopted home. In the Baltic he was buffeted by gales that drove him a hundred miles back from his course. In England he stayed less than a year because the Civil War broke out and turned men’s minds to other things than Pansophy. In Sweden he found superficial approval but ultimate scepticism from the Chancellor, Axel Oxenstierna and bound himself to a contract for which he had neither aptitude nor liking. In West Prussia he laboured for nearly six years to fulfil that contract and at the same time to fulfil his mission. The return ‘home’ (for that was how he thought of Leszno) brought fresh sorrows and fresh disappointments – the death of his wife, Dorothy, the abandonment of Bohemia by the signatories of the Treaty of Osnabrück, his election to be Senior Bishop of a Church on the verge of extinction. Only a profound sense of vocation could have energized him to embark upon a new project in Hungary – after he had provided for his younger children by marrying a third wife, Jane Gajus. The immediate objective was to reform the Grammar School of Saros Patak but for him it was a means to an end. He was resolved, as the Rector of the School wrote to Samuel Hartlib, ‘to devote himself wholly to pansophical studies.’9 There was no reason why he should not have combined the two, but before he could do so he was recalled to Leszno by threatening dangers. On April 26, 1656, the final disaster of Leszno fell upon him, he being then just over sixty-four years of age. On that day Polish soldiers, having occupied the city, proceeded to destroy it with senseless brutality. Comenius managed to bury his manuscripts and books and escape with his family into Silesia. The city of Leszno burned for three days and with it Comenius had every reason to think that his writings were irretrievably lost. After great hardships he eventually reached Amsterdam where he was received with hospitality and kindness. There he stayed for the rest of his life and thus ended his wanderings in the wilderness. But the Promised Land was still beyond Jordan.

In some ways the last fourteen years were the most remarkable. Superficially they were years of frustration, feebleness and failure. The dreams of the restoration of Bohemia were – only dreams. The prophecies on which he staked his reputation were – only delusions. The Millenium was a mirage; Pansophy a discarded slogan. One after another his contemporaries and intimate associates preceded him to the grave – Samuel Hartlib, Laurence de Geer, Peter Figulus and the wife of his old age, Jane.

But yet something of greatness remained. Of course, he should have conceded the victory to fate but he refused to accept defeat. Within a year of the destruction of his manuscripts he was feverishly preparing for the press a new edition of 1,000 odd pages of his surviving didactic works – the Opera Didactica Omnia of 1657. Though the Church of the Brethren was scattered and disorganized he proceeded to raise and administer very considerable funds for their relief. His closing years derived their strength from his indomitable resolve to bequeath to posterity the pansophic wisdom rejected by his contemporaries and to that end to urge solemnly upon his son, Daniel, and his most intimate assistant, Christian Nigrinus, the duty of publishing his gre...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Contents

- PREFACE

- 1. INTRODUCTION

- PART I. SOURCES AND DEVELOPMENT

- 2. THE CONCEPT OF THE GOOD MAN

- 3. THE CONCEPT OF ENCYCLOPAEDIC KNOWLEDGE

- 4. THE CONCEPT OF THE GOOD SOCIETY

- 5. THE CONCEPT OF DIDACTIC PROCESS

- PART II. ASPECTS OF UNIVERSAL EDUCATION

- 6. WISDOM

- 7. LANGUAGE

- 8. REFORM

- 9. THEORY AND PRACTICE OF EDUCATION

- PART III. INSTRUMENTS OF UNIVERSAL EDUCATION

- 10. SCHOOLS

- 11. TEACHERS

- 12. BOOKS

- 13. CONCLUSION

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- APPENDIX

- INDEX