![]()

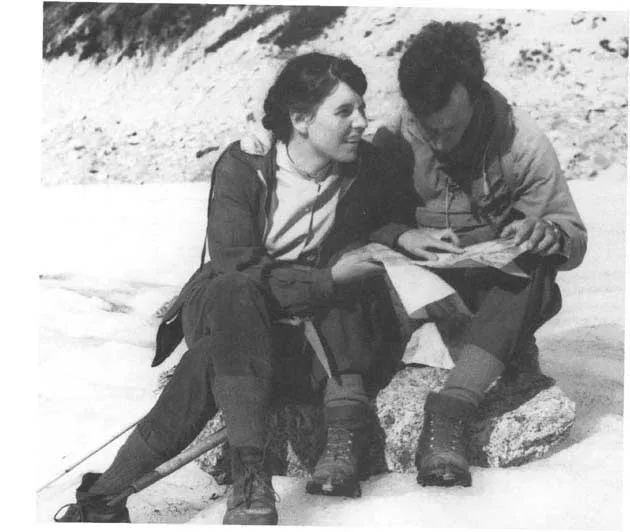

Frontispiece Jean and Dick Grove on the Aletsch Glacier, 1961

1

INTRODUCTION

Climatic changes come on several different timescales. Between short-term fluctuations lasting a few years such as El Niños, and changes extending over thousands of years such as glacial and interglacial periods, there are variations over a few centuries that may have profound effects on natural phenomena and human affairs. It is variations on this scale, stretching over several generations, with which we are mainly concerned in studying the Little Ice Age. It was a period that may be seen as beginning in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries (Porter 1986, Grove 2001b) and culminating between the mid sixteenth and the mid nineteenth centuries when glaciers were bigger than they were in the twentieth century or had been in the tenth to twelfth centuries. It was also a period of lower temperature over most of the globe, sufficiently marked to have had important consequences, especially in certain sensitive areas in high latitudes and at high altitudes where conditions for plant growth and agriculture are marginal.

For hundreds of years in the ‘High Middle Ages’ climatic conditions in Europe had been kind; there were few poor harvests and famines were infrequent. The pack ice in the Arctic lay far to the north and long sea voyages could be made in the small craft then in use. Communications between Scandinavia, Iceland and Greenland were easier than they were to be again until the twentieth century. Icelanders made their first trip to Greenland about AD 982 and later they reached the Canadian Arctic and may even have penetrated the North West Passage. Grain was grown in Iceland and even in Greenland; the northern fisheries flourished and in mainland Europe vineyards were in production 500 km north of their present limits.

The beneficent times came to an end. Sea ice and stormier seas made the passages between Norway, Iceland and Greenland more difficult after AD 1200; the last report of a voyage to Vinland was made in 1347 (Gad 1970). Life in Greenland became harder; the people were cut off from Iceland and eventually disappeared from history towards the end of the fifteenth century. Grain would no longer ripen in Iceland, first in the north and later in the south and east. As the northern winters became colder, fish migrations took different tracks and life became tougher for fishermen as well as for farmers. In mainland Europe, disastrous harvests were experienced in the latter part of the thirteenth and in the early fourteenth centuries, with famines in England in 1272,1277,1283,1292 and 1311. The years between 1314 and 1319 saw harvests fail in nearly every part of Europe (Grove 1996). Extremes of weather were greater, with severe winters and unusually hot or wet summers. In consequence the boundaries of cultivation contracted, though there were of course other forces as well as climate operating at the time.

In these late medieval times and in succeeding centuries, the impact of climatic fluctuations was felt most painfully and persistently in highland areas. Cultivated areas suffered especially in the uplands of maritime regions, such as the Lammermuir hills of southeast Scotland. In the last few centuries glaciers have advanced in the mountains of Alpine Europe and Scandinavia, in the northlands, and indeed in most other moist and cold parts of the world. In the decades between the late sixteenth and late seventeenth centuries European glaciers swelled and their tongues advanced, destroying high farms and damaging mountain villages. Streams fed from glaciers flooded more frequently, sometimes catastrophically. In many areas this kind of hazard was compounded by landslides and avalanches triggered by increased precipitation and the greater glacial activity associated with it.

The relationship between glacial behaviour and meteorological control is delicate and complicated. The researches of H. W. Ahlmann (1949) and his pupils in Scandinavia and of the Innsbruck group led by H. H. Hoinkes (1970) laid firm foundations for understanding it. If the accumulation of snow and ice during a winter accumulation season exceeds the ice wastage in the following summer, glaciers increase in volume and are said to have positive mass balances. If the wastage is greater than the accumulation, glaciers shrink and their budgets are said to be negative. If a series of positive balances occurs, the volume of ice moving downslope increases and eventually the glacier front advances. The conditions most favourable for positive budgets or mass balances are given by plentiful precipitation in winter and short cool summers causing minimum wastage or ablation. There is a lag between the onset of a particular climatic change and the response of a glacier terminus, which depends on the topography of the glacier and its valley and the flow characteristics of the ice mass. Small temperate valley glaciers with a rapid turnover of ice will respond in a few years; valley glaciers of moderate size in Austria have a response time of about seven years; some glaciers in the Cascades of the northwest United States respond over several decades. Large icecaps have much longer lag periods. Details may be found in Paterson's (1981) Physics of Glaciers.

Comparison of glacier behaviour and meteorological records over the instrumental period of the last two centuries provides a basis for extrapolating the climatic record into the past. Manley's (1974) long record of mean monthly temperatures for central England between 1659 and 1973, the result of careful integration of data from diverse records, is extremely valuable because it covers a good deal of the Little Ice Age and allows an impression to be gained of the regional temperature changes associated with the comparatively local glacier fluctuations in Europe. The behaviour of glaciers provides us with one of the most useful indicators of past climatic history for places and times lacking instrumental records, so long as the histories of sensitive glaciers with short response times are used.

Parry's (e.g. 1978) studies of the variations in the extent of cultivated land in upland Britain provided a deeper understanding of the economic and social consequences of climatic fluctuations back into medieval times. Hubert Lamb and his successors in the Climatic Research Group at Norwich extended our knowledge of past climatic conditions (Lamb 1972b, 1977,1982). There is an increasing volume of evidence indicating the importance for agriculture and rural prosperity of long-term change in precipitation and temperature. This has necessitated a reconsideration of the influence of climatic change on the demographic and economic decline in the fourteenth century so long attributed to the Black Death (Lamb 1977: 454–7, Grove 1996).

Historians have long been inclined not only to overlook but deliberately to discount the influence of climatic change on human affairs (Russell 1948, van Bath 1963, Hoskins 1968). Even Le Roy Ladurie (1971), despite his substantial book on the history of glaciation in Europe, Times of Feast, Times of Famine, is undecided on whether a difference in secular mean temperature of 1 °C has any substantial influence on agriculture and other human activities. These negative or agnostic attitudes may be explained in part by historians having made use of climatic chronologies that are now known to be incorrect (e.g. Britton 1937, Brooks 1949). Some early climatic historians were less rigorous in their use of sources than is now required and they often made extensive use of compilations and other secondary material, some of which were unreliable (Bell and Ogilvie 1978).

Studies of the Little Ice Age, and also of climatic variations on a similar scale in the more distant past, are very significant for the future. The great importance of the potential for global warming resulting from human activity and particularly the burning of fossil fuels is universally recognized. It is evidently essential to try to distinguish between climatic changes that are essentially natural and those that caused by human activity.

This book brings up to date The Little Ice Age by referring to the results of the very numerous studies that have been made since the mid 1980s. As in the first edition, the early chapters, here in Part 1, present a history of the Little Ice Age based on the records of glacier advance and retreat in northwest Europe and the Pyrenees. Information is then brought together about the behaviour of glaciers in this period in other mountainous parts of the world, including parts of Antarctica. In Part 2, the Little Ice Age is set in the longer time perspective of the Holocene, the period since the time of the Last Glaciation during which, in the words of a famous prehistorian, ‘man has made himself (Childe 1936). In Part 3 a completely new chapter presents the climatic results of analysing cores from ice sheets and from ocean floor sediments, especially in the Holocene, setting the current interglacial in the time perspective of the Quaternary Period. A fresh attempt is made to throw light on the possible causes of the Little Ice Age and, finally, an assessment is made of its significance for an understanding of human affairs.

1.1 THE TERM ‘LITTLE ICE AGE’ AND THE TITLE OF THIS BOOK

The term ‘Little Ice Age’ is widely used to describe the period lasting a few centuries between the Middle Ages and the warming of the first half of the twentieth century, a period during which glaciers in many parts of the world expanded and fluctuated about more advanced positions than those they occupied in the centuries before or after this generally cooler interval. A number of objections have been made to the employment of this term ‘Little Ice Age’ and these must be considered before the nature of the phenomena involved is explored.

The main objection is that the term was originally applied to a quite different time period, that it is now used in several different ways by current authors, and that as far as the dominant usage is concerned it is a misnomer. It is also argued that the Little Ice Age was not worldwide, that continental glaciation did not increase, and that ‘there was not any sustained low global temperature during the period’ (Landsberg 1985, Bradley and Jones 1992c), in short that it was not an Ice Age and was insignificant in scale (Landsberg personal communication 1983).

It is certainly true that Matthes (1939), who introduced the term Little Ice Age into scientific literature, intended it to describe an ‘epoch of renewed but moderate glaciation which followed the warmest part of the Holocene’. Matthes was a very close observer who was especially concerned with the glaciers of the Sierra Nevada of California, which he believed would not have survived the warmth of the climatic optimum of the mid Holocene. These little glaciers had at first been mistaken for snowfields and it was not until 1872 that John Muir was able to demonstrate that they were formed of moving ice. Matthes noted the fresh appearance of their frontal moraines:

they are made up of many small terminal moraines, laid against and on top of each other, as is clearly shown in instances where individual moraines lie spread out in a series one behind another, with concentrically curving crests. They record for each glacier many repeated advances, all of approximately the same magnitude. How many centuries of glacier oscillation are represented by these moraine accumulations it is difficult to estimate.

Matthes had no means of dating the features he described but he concluded that the glaciers had reformed after the climatic optimum and estimated that they might have reappeared ‘as recently as about 2000 BC’, although he recognized that larger icestreams such as those on Mt Rainier had probably persisted since the Ice Age.

Matthes (1950) was well aware of the record of repeated glacial advances in Europe during the past 400 years and the extent of the recession after 1850, which he regarded as ‘a turning point in the modern glacial history of central Europe; for since then the trend of climate, not only in Europe but throughout the world, has been distinctly mi...