eBook - ePub

Enhancing Marital Intimacy Through Facilitating Cognitive Self Disclosure

- 246 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Enhancing Marital Intimacy Through Facilitating Cognitive Self Disclosure

About this book

First published in 1988. This text describes a type of psychotherapy designed to increase marital intimacy, thus improving family functioning. The focus of this book is marriage as a psychological relationship. This is, then, a book about the quality of the relationship between a woman and a man in marriage and an approach to helping couples and families who have problems with intimacy.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Enhancing Marital Intimacy Through Facilitating Cognitive Self Disclosure by Edward M. Waring in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Mental Health in Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Enhancing

Marital Intimacy

Through

Cognitive Self Disclosure

In 1978 a review of family therapy in schizophrenia was published (Waring, 1978). This paper was a result of eight years of experience in working with families in which one or more of the offspring had a diagnosis of schizophrenia. One of the conclusions of that review article was “the parents of schizophrenics show more conflict and disharmony than the parents of other psychiatric patients.” In retrospect this conclusion may be incorrect. However, some schizophrenic patients seemed to be sensitive to the quality of their parents' relationship. Relapse in some patients occurred when intimacy between the parents was low.

In my attempts to understand this clinical phenomenon, I happened to read a theory of dyadic interpersonal relationships developed by Schutz (1966). His theory suggested that there are three independent dimensions of interpersonal relationships, which he called inclusion, control, and affection. He suggested that in enduring relationships such as marriage, the affection dimension is the major variable which determines marital satisfaction. This theory was in keeping with the observation of Bowen that “emotional divorce” in the parents of schizophrenics might be related to the course and outcome of the disorder (Bowen, Dysinger, & Basamania, 1959). These two theories suggested that any intervention which decreased the amount of expressed hostility between the parents (or conversely increased supportive statements or closeness) might lead to an improvement in the schizophrenic offspring's symptomatology.

The theory was simple, led to specific action, gave hope, and was capable of verification through treatment success or failure. If I could enhance the parents' intimacy, the course and outcome of the offspring's schizophrenia should improve.

I began to experiment with this approach. The parents were seen alone as a couple. (The schizophrenic offspring was usually seen by an independent psychiatrist for medication and follow-up.) The first session involved an explanation to the couple of the theory of enhancing intimacy to the couple, thus explaining to them why the therapy was being used. The 10 sessions that followed involved:

1.No direct verbal communication between the couple during the session.

2.Each spouse would talk only to me.

3.I discouraged any emotional display during the session.

4.One spouse initiated discussion about his or her thoughts about the disorder and I asked cognitive questions about the problem at hand, including “What is your theory?” I did not ask about feelings but only about the spouses' thinking.

5.When I thought that one spouse had exhausted the topic, I turned to the other spouse and said “What were you thinking while your spouse was talking?” I followed the same procedure throughout the sessions.

The rationale for this type of intervention at the time was:

1.Only the parents are included in the therapy session— other family members are excluded from the emotional system between the parents—thus taking the schizophrenic offspring outside of the couple's emotional system and allowing more cognitive control.

2.The therapist rigidly attempts to stop any emotional interaction between the couple and thus models a different form and method of communication (later to be called cognitive self-disclosure).

3.The therapy was thought to increase the amount of listening done by the spouses, increase the amount of time the spouses spend together, and increase their understanding of one another. This would decrease the use of emotion for control and reduce hostility and criticism leading to an increase in intimacy.

In preliminary experience, this form of family therapy, which was based on an empirical finding of increased marital disharmony that might affect the course and outcome of schizophrenia, had encouraging results.

In 1980 the first preliminary report of this technique was published under the term Cognitive Family Therapy (Russell, Russell, & Waring, 1980). This brief description of the treatment of 22 chaotic, acting-out families in hospital and private practice reported a good outcome for a method employing cognitive skills.

In this paper, the theory behind the approach was articulated. The theory stated that in all families with psychopathology, a necessary variable is a “dysfunctional affective potential” in the marital relationship. This was conceptualized as a failure of the parents to develop interpersonal intimacy because they did not have the modeling in their own families of origin. The technique of cognitive self-disclosure attempted to suppress feelings of criticism and hostility and enhance intimacy in the parents' marriage. Family functioning then improves and there is a positive effect on existing psychopathology. The technique allowed for a novel opportunity to “listen” to one's spouse.

The paper briefly described the method of assessment which is presented in some detail in Chapter 3. The paper concluded that this approach provides a viable treatment choice for immature, chaotic families who frequently terminate treatment prematurely when they are encouraged to express feelings openly. Their feelings are often primitive and the technique offers the therapist the opportunity to avoid being “sucked into the system.” Of course, the paper was only a subjective report of a promising approach which provided a nonthreatening method.

Later in 1980, Lila Russell and I published a paper which not only described the technique of using self-disclosure of cognitive material in more detail but also presented the first objective data suggesting the method might be effective (Waring & Russell, 1980a). The paper was judged by the journal editors as worthy of reproduction in The International Book of Family Therapy edited by Kaslow (Waring & Russell, 1982). Some of the outcome data from that study are presented here for the first time.

Self-disclosure was defined as the process of making the private self known to other persons through words. Cognitive self-disclosure refers to revealing one's ideas, attitudes, beliefs, and theories regarding one's relationships.

Cognitive self-disclosure was differentiated from emotional disclosure, which is revealing one's feelings. Self-exposure is disclosing secret or unrevealed behavior that may be detrimental to a relationship. Self-exposure of secrets may be motivated by a wish to distance. Disclosure of negative feelings such as anger often produces distance rather than closeness. Marital intimacy was thought to be enhanced when the therapist facilitates both spouses to disclose their ideas, attitudes, beliefs, and theories about why the marriage is maladjusted and their thoughts regarding the influence of their parents' marital relationship on their own.

Intimacy was defined as one dimension of interpersonal relationships within the context of a marriage. Intimacy involves an emotional closeness, a cognitive understanding, behavioral compatibility, and mutual sexual satisfaction.

THE STUDY

The sample consisted of a consecutive series of 11 families in which an individual family member was the presenting patient. However, after individual and family assessment, family therapy was considered the treatment of choice.

These 11 cases represent a subsample of approximately 50 individual referrals for psychiatric outpatient assessment (EMW) or were referred to a general hospital consultation-liaison service in a three-month period (EMW, LR).*

Following the individual and family assessments, 18 families were informed of the nature of the study. The couples were randomly assigned to experienced or inexperienced therapists. Seven families for which family therapy was considered the treatment of choice refused to participate in the study. The reasons given were 1) preference for a specific therapist; 2) objection to completing self-report questionnaires or taping of their sessions; and 3) noncompliance with the suggestion of family therapy. These couples received this self-disclosure approach or other therapy from the authors but are not included in this study sample.

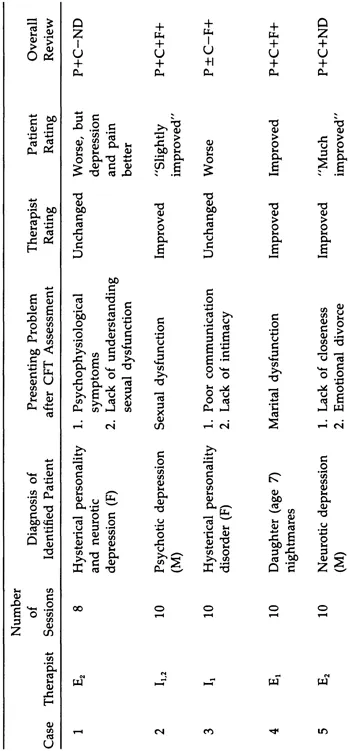

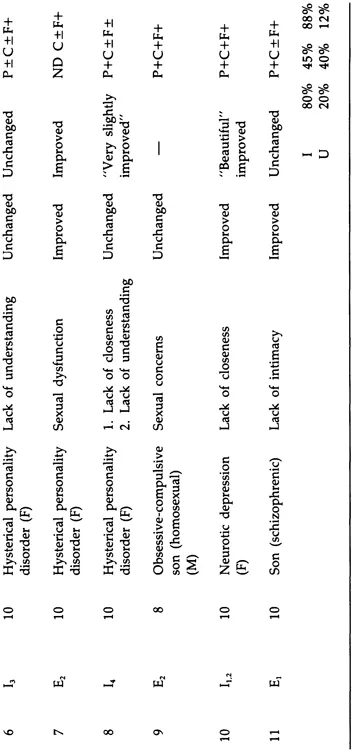

Table 1 (on pp. 10–11) presents the psychiatric diagnosis of the presenting patient and the presenting problem of the family (parents) after the evaluation interview. A spouse was the presenting patient in eight families and a child in three familes (cases 4, 9, and 11). No families were referred specifically for family therapy and only one case (case 9) was referred for marital counseling. Six cases were referred for outpatient psychiatric assessment (cases 1, 3, 4, 5, 8, and 9) and five were referred to the general hospital consultation-liaison service, those presenting with physical symptoms or overdose.

Six cases were diagnosed as having neurotic illnesses, four were diagnosed as having character disorders, and one was schizophrenic. Four cases presented as threatened or attempted suicide (cases 1, 3, 5, and 6). All but three cases (cases 3, 4, and 7) had previous psychiatric treatment-previous hospitalization (cases 2, 5, 6, 9, and 10); marital counseling (case 8); and treatment for drug abuse (case 11).

During the course of the 10 weeks of therapy, case 2 received antidepressant medication; case 3 had brief supportive sessions and demanded minor tranquilizers (which were refused) and saw a nonpsychiatrist physician; case 4 was assessed by a child psychoanalyst before and after her parents' therapy; case 9 continued lithium prescribed by another physician; and case 11 received perphenazine and was briefly hospitalized.

In summary, the sample was a difficult heterogeneous treatment group: 1) individuals had moderate to severe psychiatric illness; 2) none were referred for family therapy; and 3) the majority had previous psychiatric treatment and were referred as treatment failures. This heterogeneous group was studied because of the importance of evaluating therapies in ordinary clinical settings, and the results have implications for this approach in difficult patient populations.

All presenting patients received an individual psychiatric interview with one of the researchers (EMW). Assessment interviews were conducted by both researchers. EMW was the therapist for cases 4 and 11, and LR treated cases 1, 5, 7, and 9. The researchers are experienced family therapists.

Case 3 was treated by a nurse, cases 6 and 8 by two social work students, and cases 2 and 10 by the same nurse and a senior psychiatric resident. All had some training in family interviewing but were inexperienced in family therapy.

Table 1

Description of Couples Outcome in Cognitive Family Therapy

Description of Couples Outcome in Cognitive Family Therapy

Key: E1= experienced psychiatrist; E2 = experienced social worker; I1 = inexperienced nurse; I2 = inexperienced resident; I3 = inexperienced social worker student; I4 = inexperienced student; P = patient; C = couple; F = family (includes children, in-laws, family of origin); + = improved; - = worse; ± = unchanged; ND = no data; I = improved; U = unimproved; (F) = female; (M) = male.

The training of the nurse, social work students, and resident was of particular importance. They all attended a weekly family therapy seminar. The four “student” therapists attended a one-day workshop to train them in the technique of enhancing marital intimacy. This consisted of an introductory lecture, viewing videotapes of both assessment interviews and a cognitive self-disclosure therapy session, and role playing of assessment and therapy. They then received one hour of supervision from one of the authors for each hour of therapy.

Supervision, by audiotape, focused on whether they were doing therapy in a standardized fashion as previously described and focused on why they were not using cognitive self-disclosure if this was the case. The students uniformly had difficulty initially with the “cognitive response” approach and reacted to behavior and feeling. In all cases the students gradually began to use self-disclosure in a standardized way and the need for supervision decreased. Thus the supervision process ensured that all therapists were employing the same technique.

It must be emphasized that, although a uniformity and standardization of the technique was obtained through audiotaping and supervision of the sessions, therapist personality variables and nonspecific treatment factors were not controlled. In fact, the students were encouraged through their personality, interpersonal style, and “use of self” outside of the therapy sessions to do whatever was necessary to facilitate the families continuing the sessions.

Following the assessment interview, specific and explicit explanation of theory, therapy, and treatment contract was completed and an informed consent was obtained. The couples were then randomly assigned to one of six therapists who was next on the therapy list if they had available time. The 11 couples were requested to complete the following self-report questionnaires: General Health Questionnaire (Goldberg, 1972); Zung Depression Scale (Zung, 1963); Locke-Wallace Marital Adjustment (Locke & Wallace, 1959); Family Environment Scale (Moos & Moos, 1976); and Fundamental Interpersonal Relations Orientation-Behavior (Schutz, 1966), prior to treatment and at termination.

The General Health Questionnaire is a 60-item self-report questionnaire for the detection of nonpsychotic emotional illness (Goldberg, 1972). A symptom score greater than 12 suggests the possibility of neurotic or psychophysiological illness.

The Zung Depression Scale is a standardized self-report questionnaire which measures depressive symptoms (Zung, 1963). The Locke-Wallace is a 16-item self-report questionnaire which measures marital adjustment (Locke & Wallace, 1959).

The Family Environment Scale (FES) assesses the social climates of all types of families (Moos & Moos, 1976). In this study we focused on the measurement and description of 1) the interpersonal relationships among family members: cohesion, expressiveness, and conflict; and 2) system maintenance dimensions: organization and control (see the appendix for definitions).

The Fundamental Interpersonal Relations Orientation-Behavior (FIRO-B) is a self-report questionnaire measuring inclusion, control, and affection (Schutz, 1966). In this study we focused only on affective compatibility, which...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Full Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- 1. Enhancing Marital Intimacy Through Cognitive Self-Disclosure

- 2. The Rationale

- 3. Assessment

- 4. The Technique

- 5. Research

- 6. Summary and Conclusions

- Appendix

- References

- Index