![]()

ONE

THE MYTH OF PENNSYLVANIA STATION

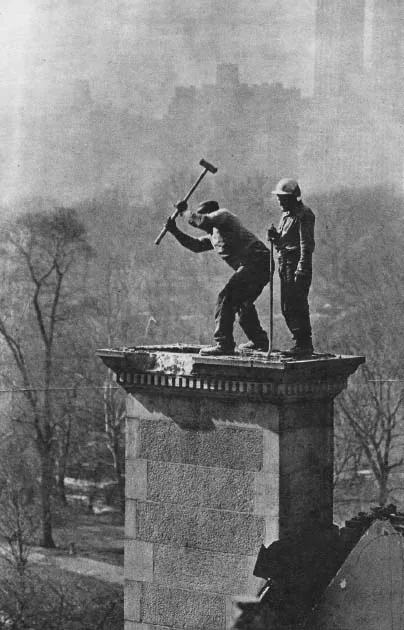

“In weekend stealth the vulture-like work of destroying another New York landmark has begun. … ‘We ain’t breaking no laws,’ said an anonymous spokesman for the anonymous wreckers. There are no laws to break, and—at the rate the city is moving on passage of its pending landmarks legislation—there will be no landmarks to save. Just new monuments to ugliness.” It was February 1965. New York City was as lawless as the legendary Wild West when it came to preserving its landmarks. Under the blazing headline of its scorching editorial, “Rape of the Brokaw Mansion,” the New York Times decried the continuing despoiling of the city.1

The lamented buildings under assault that February were the Brokaw mansions. One could not have found better poster children for the preservation cause. Helping frame the East 79th Street entrance to the Upper East Side from Central Park, their style and opulence lived up to their prominent address. Of them, the noted architecture critic of the New York Times Ada Louise Huxtable wrote, “They were among the city’s finest examples of the baronial and classical homes of New York’s kingly merchants and bankers. … They were extravagant, luxurious constructions designed with pride and pardonable ostentation.”2

The corner mansion, 1 East 79th Street, a partial replica of the sixteenth-century chateau Chenonceaux in the Loire Valley, had been built by the manufacturer, Isaac Brokaw, starting in 1887. Its neighbor to the north, 984 Fifth Avenue, was one of two twin “flamboyant gothic” houses modeled after the late-fifteenth-century Palace of Justice at Rouen, built for his sons after the turn of the century. To the east, 7 East 79th Street, designed in a “more chaste classical manner,” was the home Isaac had constructed a few years later for his daughter.3 The Brokaw mansions were just the latest landmarks to be consumed in the city’s building frenzy.

FIGURE 1.1 For more than half a century, the Isaac Brokaw mansion anchored the northeast corner of Fifth Avenue and East 79th Street. It was flanked to the north and the east by equally distinguished town houses that Brokaw had constructed for his children. The fate of this prominent corner would play a major role in advancing the passage of New York’s Landmarks Law.

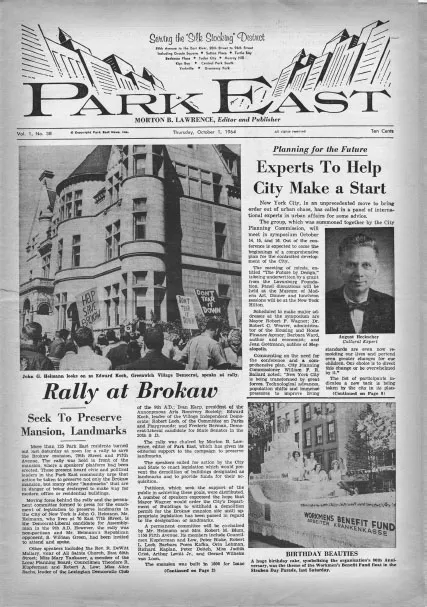

Months before on the streets of Manhattan’s usually genteel Upper East Side, a placard-waving demonstration followed the public announcement of the plans to demolish the buildings. On Saturday, September 26, 1964, a crowd of some 125 people rallied in front of the threatened mansions to hear a cadre of speakers, mostly politicians, call for the preservation of the buildings. One of those at the megaphone calling for preservation was then leader of the Village Independent Democrats, future mayor of New York, Edward I. Koch.4

The demonstrators were not alone in their call for preservation. The city’s Landmarks Preservation Commission, at this time a mayoral agency lacking the force of law, had already “designated” 1 East 79th Street as “worthy of being saved.” Coming with no legal authority or protection, that designation was virtually worthless. The newspapers also sounded the call to arms. The New York Times asked “Will there be any historic landmarks left in New York City by the time a proposed law to save them sees the light of day? Hardly a week passes when doom is not pronounced for an admired old building. The latest marked for replacement is the fabulous Brokaw mansion.”5 The New York World-Telegram proclaimed, “If City Hall is serious about preserving landmarks, it had better wake up and take firm legislative action before they’re all gone.”6 The Herald-Tribune logged in: “We have plundered and wrecked our heritage, to what end purpose? Who can truthfully say that this destruction of links with the past, this callous disregard for beauty and variety, produces a finer New York?”7 The print media was not alone and editorials echoing the same sentiments were voiced on WCBS-TV.8

FIGURE 1.2 When the news broke that the Brokaw mansion was to be demolished for the construction of a high-rise apartment building, citizens took to the streets in protest. On Saturday, September 26, 1964, future mayor Edward Koch addressed over one hundred concerned New Yorkers as they rallied to save this unprotected landmark. The event was captured in Park East, the neighborhood paper then serving the “Silk Stocking” district.

There were eleventh-hour efforts to intervene. A foundation considered buying the building for its offices. The city itself had considered acquiring the houses for a variety of possible uses, including a guesthouse for visiting dignitaries.9 Even after the demolition had begun, there were frantic efforts at the highest level. Recalled Geoffrey Platt, first chair of the Landmarks Preservation Commission, “The Mayor’s office tried to do something about that. One of the secretaries called me and said that we can hold things up until Monday, if you can think of what to do, you know, but nobody could think of anything to do. There was no mechanism. The mechanism wasn’t there.”10

Despite the passion of the people, the efforts of the politicians, and the cries of the press, nothing could save the Brokaw mansions. Anger and frustration abounded. The people, the press, and the politicians were all powerless. These were not the first buildings New Yorkers had fought to save and lost. Unknown to their defenders, they would be the last buildings New Yorkers would have to sacrifice to win the right to protect their landmarks.

The passage of New York’s Landmarks Law was a sea change for New York City. Prior to the law, efforts to save the past were isolated, episodic, and often, as with the Brokaw mansion, failures. With the law came a defined governmental process through which preservation could be advanced. Since its passage, the law has created the playing field where competing forces battle over conflicting visions for pieces of New York’s past. The law fundamentally changed the process of how New York City manages change.

To fully grasp the impact it has had on the face of the city, imagine for one frightful moment New York City without its landmarks. Conjure up your favorite New York image. Is it a quaint block in Greenwich Village, a soaring Art Deco skyscraper, a row of Greek Revival houses in Brooklyn Heights, a quiet corner of Central Park, a gracious old estate on Staten Island, a remnant of the World’s Fair in Queens, a bejeweled Broadway theatre, a tree-lined street in Riverdale? Odds are good that the special place you envisioned is either under the protection of the Landmarks Law or that some person or group is seeking such protection for it.

FIGURE 1.3 Accompanying a feature article, “The Wreck of the Brokaw Mansions,” in the April 11, 1965 issue of the New York Herald-Tribune, this stark image dramatizes the extreme vulnerability of New York’s architectural treasures prior to the passage of New York’s Landmarks Law. The demolition of the Brokaw mansions would be the last major loss the city would have to endure before Mayor Wagner signed the landmarks legislation into law on April 19, 1965. RT52840.

It is remarkable that the origins of a law so dramatically impacting the cityscape of one of the greatest cities in the world has generated so little curiosity. The law has now been in place so long and served the city so well that its very existence is only rarely questioned—and if it is, only by the most extreme political elements. Today, it is not whether the city should protect its landmarks that is debated, but what those landmarks should be and how they should be treated.

To most, it seems unremarkable that New York City has both the desire and the legal means to protect its past. Yet, looking at the city’s history, this is not only remarkable, but extraordinary. The Landmarks Law contradicts one of the city’s most chronic characteristic traits: its bullish pride in the new. How the city tempered its raging lust for the new, traditionally at the expense of the old, is an amazing yet largely unappreciated story.

Historically, it has been change, not preservation, that has been the constant in New York City. In the 1840s, Philip Hone wrote in his famous diaries: “Overturn! Overturn! Overturn! is the maxim of New York … one generation of men seem studious to remove all relics of those which preceded them.”11 Walt Whitman identified it in an 1845 essay as the city’s “Pull-down-and-build-over again spirit.” In more recent times, former landmarks commissioner Barbaralee Diamonstein-Spielvogel eloquently summed it up: “New York’s quintessential characteristic is its quicksilver quality, its ability to transform itself not just from year to year, but almost from day to day.”12

Time magazine captured these conflicting emotions when it wrote in 1950, “Nothing makes a New Yorker happier than the sight of an old building rich in memories of the past—unless it is tearing the damn thing down and replacing it with something in chromium and plate glass, with no traditions at all.”13 How did preservation grow to become such a strong civic emotion in a city whose favorite pasttime is real estate development? How did the instinct to preserve become so much a part of the city’s persona? Was it always latent in the city’s genes or was it a latter mutation? Seen in this context, one not only has to marvel that the law ever came into being, but also wonder how it came to triumph over that other, seemingly more dominant New York trait.

From a perspective colored by the rising dust of the stunningly beautiful and historically important buildings New York City was regularly destroying until 1965, one sees the question differently. Knowing also that other American cities were well ahead of New York in efforts to preserve their heritage, one instead inquires: Why did it take New Yorkers so long to win the right to protect their landmarks?

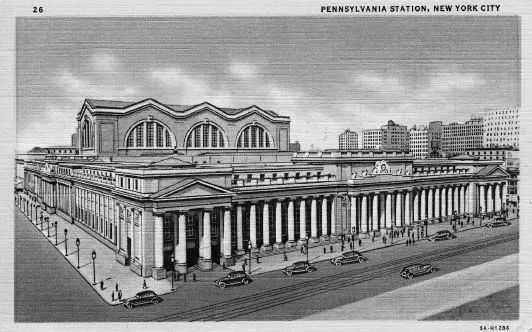

However framed, for years the question of how New Yorkers won the right to protect their landmarks (to the extent that anyone inquired) received the standard answer: the law was the result of the monumental and shocking loss of the legendary Pennsylvania Station. Indeed, Pennsylvania Station has become a preservation icon. In New York, its demolition is seen as the defining event of the movement’s history and the genesis of the Landmarks Law. So prevalent is this imagery of preservation policy emerging from such a spectacular loss that preservationists in other cities often talk of their “Pennsylvania Station,” the great loss their community had to endure to shock it into taking action to preserve their past.

FIGURE 1.4 For those who never experienced historic Pennsylvania Station, it is hard to imagine just how vast a structure it actually was. Occupying two full city blocks, over 500 buildings were cleared for its construction. Its demolition would take three years.

The Pennsylvania Station explanation for the birth of New York City’s Landmarks Law is a captivating one. Consider the powerful imagery of the building itself. Thomas Wolfe’s famous passage lyrically captures its romance as the place where “the voice of time remained aloof and unperturbed, a drowsy and eternal murmur below the immense and distant roof.”14 Physically, it was massive: “nine acres of travertine and granite, 84 Doric...