- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Inner City Regeneration

About this book

This book covers all the main aspects of government policy and practice in British inner city regeneration. Chapters deal with the development of policy, agencies for regeneration, housing, social issues. The UK edxperience is compared with that of other countries, particularly the USA, and past achievements and future prospects are considered.

This book was first published in 1982.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Inner City Regeneration by Robert K. Home in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias físicas & Geografía. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The development of inner city policy

The inner city problem is a historical legacy left by Britain’s imperial past, the Industrial Revolution and 19th century urbanization. It was identified as a major new concern of Government in the 1970s by a process of policy formulation which absorbed a number of urban, spatial and economic problems within the broadly defined inner city problem. This first chapter examines briefly British city development in the 19th and 20th centuries, and the emergence of the principal elements in the inner city problem. The creation of the Urban Programme in 1968 is then taken as the starting point for an account of the development of government thinking on inner cities, traced through Community Development Programmes, Inner Areas Studies and the Inner City White Paper 1977, to the new initiatives by Labour and Conservative Governments since 1977, and the growth of disorder after 1980.

The rise and fall of the industrial city

The origins of the inner city problem lie in the 19th century, when Britain experienced industrialization and urbanization on an unprecedented scale. The population of the nation grew nearly four times during that century, and the proportion of people living in towns with a population over 20 000 rose from 17 to 77%. Job opportunities brought migrants pouring into the cities, where they commonly worked long hours at physically demanding, low-paid jobs, and lived in overcrowded and insanitary rented rooms.

Figure 1 The congested industrial city. This photograph (Commercial Street, East London, 1907) shows the high-density buildings, mixed uses, and congestion of traffic and people that characterized the inner city until it began to empty in the mid-20th century.

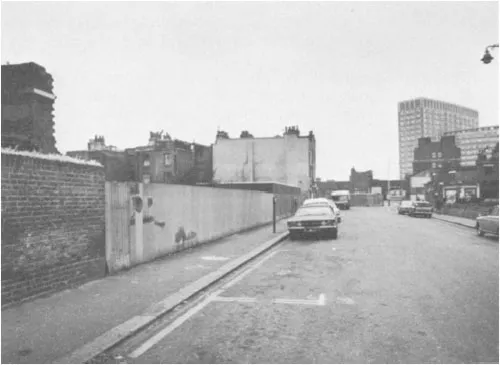

Figure 2 The inner city today. A typical street scene showing boarded-up vacant land, old buildings in poor condition, exposed gable ends left over by demolition, temporary buildings, office blocks, on-street parking, and few people.

The physical development of the cities was as dramatic as their population growth. Working class housing was built in great quantities but was often insufficient to meet the demand. It was usually cramped because of the difficulties of ensuring an adequate return on capital investment for the developers and the need for workers to be within walking distance of their work. The types of housing varied regionally: in northern towns back-to-backs (typically one room up, one room down, with no through ventilation) were built and in London, multi-storey tenements were constructed because of the pressure on land. The Industrial Revolution created bigger and more specialized work-places than before, for example, multi-storey mills for the textile and other industries, docks, warehouses and construction sites for the great civil engineering projects. New modes of transport were brought into the cities, clearing slums and displacing people in the process: these included canals, followed by the railway, followed by the growth of horse-drawn and then horseless road traffic.

An unprecedented development and improvement of public services also occurred in the 19th century industrial city, for example, water supply, cemeteries, sewers, refuse collection and street cleansing (a working horse produces up to seven tons of dung a year). Public buildings proliferated: hospitals, schools, baths, libraries and town halls. The first Public Health Act, passed in 1848, was followed by improved building and town planning controls, wider streets and lower densities of buildings. Towards the end of the century enterprising municipal authorities undertook the supply of gas, electricity and water, as well as housing for the working classes.

During the 20th century, by contrast, the industrial city, essentially a creation of the Victorian period, has been in decline. The population of Britain’s major cities seems to have reached a peak in about 1940 and thereafter to have stabilized or declined, although the extent to which this decline affected the inner areas was little realized until after the 1971 census. The strains created by social and economic change have led to the inner city problem.

Perhaps the most significant factor in inner city decline has been the increased mobility of goods and people. The development of cheap mass travel – railway, underground, tram and bus – first allowed people to escape from the crowded inner areas to live in the suburbs and then in the third quarter of the century the rapid increase in the number of cars and other vehicles created further opportunities for mobility as well as using up inner city land for roads and car parks.

This improved transport and mobility led to the large-scale decentralization of jobs and people. Other contributory factors were the processes of industrial rationalization, the Government’s commitment after the Second World War to dispersing employment to new towns and depressed regions, increased home ownership and building society policies favouring modern suburban housing, and the disruptions of slum clearance and redevelopment. This decentralization coincided with the post-war wave of immigration to Britain, particularly New Commonwealth workers drawn by the demand for labour in the 1950s: as the indigenous population moved out of the inner areas, ethnic minorities moved in, because there they could find cheap housing and a large job market.

By the 1970s the principal elements of the so-called inner city problem could be seen clearly and were recognized by the Inner City White Paper in 1977:

Many of the inner areas surrounding the centres of our cities suffer . . . from economic decline, physical decay and adverse social conditions . . . The inner parts of our cities ought not to be left to decay. It would mean leaving large numbers of people to face a future of declining job opportunities, a squalid environment, deteriorating housing and declining public services.

Physically the inner city comprises 20th century redevelopment and the surviving parts of the 19th century industrial city. On the one hand, massive redevelopment, by both public and private sectors, has not provided the ‘New Jerusalem’ that socialist visionaries and planners had hoped for after the Second World War. On the other hand, the 19th century industrial city has left a legacy of buildings and infrastructure unsuitable for modern needs and which are expensive to renew or improve: e.g. warehouses and mills, churches and cemeteries, sewers and electricity stations. The physical form of the inner city is further complicated by a historical confusion of land ownership and uses.

The inner city also seems to be in social and economic decline. Employment is at the heart of the problem, with jobs disappearing, especially in manufacturing and traditional industries, and workers moving out for better prospects elsewhere. The inner city residents left behind suffer from poverty, deprivation, unemployment, disruptive redevelopment and racial disharmony, while the population and rate base is inadequate to improve their living conditions. As the Inner City White Paper stated:

Some of the changes which have taken place are due to social and economic forces which could be reversed only with great difficulty or at unacceptable cost. But . . . it should be possible now to change the thrust of the policies which have assisted large-scale decentralization and in the course of time to stem the decline, achieve a more balanced structure of jobs and population within our cities, and create healthier local economies (p. 5).

The White Paper’s analysis, however, failed to take sufficient account of the powerful forces of technological change, de-industrialization and economic recession, which, since it was written, have accelerated the decline of traditional manufacturing, the disappearance of jobs and changes in job skills, thus aggravating the inner city problem.

Towards an inner city policy

The development of government thinking on inner cities can be traced to the policy initiatives of the Labour Government of Harold Wilson (1964–70). ‘Urban deprivation’, although not always so called, has long been a topic of periodic public concern, reported on by social investigators like Mayhew, Booth and Rowntree. But the Second World War, post-war redevelopment and increased prosperity temporarily diverted attention in Britain from the ever-present problem of poverty. The Conservatives’ slogan in the 1950s was ‘You’ve never had it so good’. The Wilson government, the first Labour Government for twelve years, was concerned that people should have equality of access to the new opportunities and social researchers developed concepts like ‘deprived areas’ (seen as islands of poverty in the general sea of prosperity) and the ‘cycle of poverty’ (in which families or indeed whole communities transmitted cultural disadvantages from one generation to the next like a disease).

Attention was drawn to inner city problems by the issue of race and immigration. The non-white population of Britain was over half a million in 1966, approximately an eight-fold increase since the Second World War, and was largely concentrated in the inner areas. Following the introduction of immigration controls the Government began to realize that the new immigrant communities were experiencing acute problems of adjustment, particularly in housing, education and employment, and it was feared that the race riots of 1967–8 in the USA might also happen in Britain. The speeches of the then Conservative politician Enoch Powell envisaged racial conflict destroying the fabric of British society: ‘Like the Romans, I seem to see the River Tiber foaming with much blood’ (20 April 1968). The Wilson Government at the time was also worried about its loss of political support in Labour’s traditional strongholds, the cities. Against this background the Government took three initiatives which were important in the development of inner city policy: educational priority areas, the urban programme and the community development programme.

The concept of educational priority areas (EPAs) originated with the Plowden Report, Children and their Primary Schools 1967. This was one of several Government reports which identified deprived areas, mainly in the inner cities, whose special needs required positive discrimination by Government in allocating resources. This area-based approach remained an important tool of inner city policy, applied to housing problems through different kinds of housing improvement areas, and more recently to economic problems through industrial improvement areas and enterprise zones. In the area-based approach, areas for special attention are identified by analysis and correlation of the available statistical indicators, a process aided by improved technologies for information-handling. Critics of the approach argue that the statistics themselves only identify that which can be measured, obscuring unquantifiable but significant factors, and that the problems of deprivation have deep structural causes which initiatives based on arbitrary geographical boundaries cannot affect.

In 1968 Prime Minister Wilson, responding to Powell’s inflammatory speeches, and borrowing the idea from President Johnson’s Poverty Programme in the USA, announced the setting up of an Urban Programme, intended in his words ‘to deal with the problems of areas where immigration had been at a high rate’. The initial funding was to be £20–25 million over four years, and the statutory basis was the Local Government Grants (Social Needs) Act 1969, with the Home Office taking the main co-ordinating role. Until the Urban Programme arrangements were changed in 1977, several thousand projects, proposed by local authorities and voluntary organizations, were approved. The emphasis was on capital rather than recurring expenditure, on experimental or innovative projects supplementing main programmes, and on educational projects like pre-school playgroups. There seems to have been little systematic setting of objectives, nor much analysis of relative priorities or of the geographical distribution of projects, with the result that some local authorities were proportionately overfunded or underfunded relative to their degree of deprivation.

The third initiative was the Community Development Project (CDP), begun in 1969 as ‘a neighbourhood-based experiment aimed at finding new ways of meeting the needs of people living in areas of high social deprivation’ (Home Secretary Callaghan speaking in Parliament).

Twelve local projects, with a central team at the Home Office, were established in suitably deprived neighbourhoods with populations of 10 000–20 000, mostly in inner areas. Each project ran for about five years, with project teams affiliated to a local centre of higher education. The emphasis was on improving the co-ordination and responsiveness of local services, and on ‘action research’, whereby the researchers sought to involve themselves in community organizations. As the projects developed, the local teams not only clashed with their sponsoring local authorities, but increasingly criticized the Home Office’s apparent assumption that poverty results from a social pathology, the ‘cycle of poverty’, which can be eradicated. Their experience and research, particularly on the history of industrial politics in their areas, led them to a more radical view, seeing deprivation initiatives as ‘not about eradicating poverty at all, but managing poor people . . . The basic dilemma for the state remains the same – how best to respond to the needs of capital on the one hand and maintain the consent of the working class on the other’ (Gilding the Ghetto, p. 63). This structural conflict view of society was too much for the Home Office, which closed down the CDP in 1977 with no official final report. The CDP workers produced the independent report, Gilding the Ghetto, with the disclaimer that ‘This report does not necessarily reflect the views of the Home Office or any of the local authorities’.

The Conservative Government of Edward Heath succeeded Wilson from 1970 to 1974. The newly created Department of the Environment, a merger of three ministries, under its Secretary of State, Peter Walker, began to take the initiative on urban problems away from the Home Office, although the latter did establish an Urban Deprivation Unit in 1973 and the Comprehensive Community Programme experiments in 1974. Walker, influenced by the rise of community-based groups, particularly the Shelter Neighbourhood Action Project (SNAP) in Liverpool, began to advocate a ‘total approach’ to urban problems, and in the Making Towns Better studies in 1972–3 commissioned management consultants to examine three northern towns and advise how to develop this approach. While these reports influenced the management style of local government, which was reorganized in 1974, more important in the evolution of inner city policy were the Inner Area Studies prepared between 1972 and 1977.

In these studies planning consultants worked on three inner areas: Small Heath, Birmingham (Llewelyn-Davies, Weeks, Forestier-Walker and Bor); Stockwell, south London (Shankland Cox Partnership with the Institute of Community Studies); and Liverpool, Merseyside (Hugh Wilson and Lewis Womersley, with two other consultant firms). The Department of the Environment gave them four instructions: to suggest definitions for inner areas and their problems; to experiment with environmental improvements; to investigate the concept of area management; and to provide a basis for conclusions on statutory powers, resources and techniques. The consultants combined the action research approach of the CDPs with environmental improvements and other projects. All provided lengthy final reports as well as numerous interim reports and studies. The consultants’ final reports were summarized in a Department of the Environment publication, Inner Area Studies: Liverpool, Birmingham and Lambeth 1977.

The Liverpool study emphasized ‘a total approach towards the inner area which would build up a comprehensive understanding of its problems, and take concerted action for their solution’ {Summary, p. 12). This total approach would be pursued through four programmes: ‘(a) promoting the economic development of inner Liverpool; (b) expanding opportunities for training; (c) improving access to housin...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Contents

- Figures

- Acknowledgments

- 1 The development of inner city policy

- 2 The agencies for inner city regeneration

- 3 Planning and land issues

- 4 Economic regeneration

- 5 Improving the housing stock

- 6 Social provision

- 7 Four governmental experiments

- 8 Learning from overseas experience

- 9 A future for the inner city

- References and further reading

- Appendix I Selected statistics and indicators

- Appendix II Five English inner cities

- Appendix III Inner city regeneration projects

- Index