![]()

Chapter One

Andalusian Journey: An Introduction

Flamenco, the music that originated in southern Spain over one hundred and fifty years ago, has long captured the hearts and imaginations of people the world over and has become a symbol of all that is Spanish. The present study is a musical, social and cultural investigation of flamenco music with a focus on cantaoras (female flamenco singers). I examine importance of women to the flamenco tradition both in the past and the present. My book explores the contributions of women to the flamenco tradition, their essential role in the transmission and preservation of culture, as well as their participation as active agents of creativity and change within flamenco performance. My study is situated in socio-political currents that have been reshaping Spanish society since the early twentieth century, in particular the changing conditions for women in post-Franco Spain. Flamenco is a complex of practices: musical, physical, verbal and social, that has served as a site for the creation and negotiation of complex, multi-layered and often conflicting identities of nation, region, ethnicity and gender. I am interested in the discourse about and the performance practice within contemporary flamenco as emblematic of the uneven processes that have characterized modernization in Spain, and as a metaphor for the impassioned and often contradictory cultural practices of Andalusia.

I present a new approach to the study of women in flamenco, one with an ethnomusicological perspective. Flamenco music has traditionally been considered a male genre, with the exception of the role of female dancers. The subject of female singers has never been adequately addressed; that is, the essential role played by women as creators and transmitters of cante (song), as performers of a tradition that is transforming while at the same time it is strongly rooted in culture and is in fact emblematic of Andalusian culture. This book is an exploration of women flamenco singer’s voices, stories and experiences, in which I endeavor to contribute to current ethnomusicology and feminist scholarship as well as to flamenco research. My interest in female singers and their involvement in musical transformations taking place within the flamenco complex includes questions of musical style, hybridity, new texts, emotional content and symbolic meanings. The negotiation of complex levels of identity as they shape stylistic innovations, the expanding socio-cultural matrix of flamenco and the individual agency of women artists are central to my study. Conscious manipulation of musical style and lyrical content reveal the central role played by women who have been instrumental in creating and shaping flamenco. An analysis of the elements being retained as the more “authentic” or traditional flamenco and those open to innovation, as well as an exploration of the role played by women in this process, contributes to an understanding of cultural values and social/class and gender identities in the process of construction.

Background of the Research

My many years of interest in Spanish culture, from the moving poetry of García Lorca to the evocative sound of the flamenco guitar, led me to study the dance, attend local flamenco performances and finally travel to Spain several times. Despite my long-standing interest, it came as a surprise to me to discover how many powerful and compelling women singers were represented in flamenco. I was accustomed to thinking of women in flamenco primarily as dancers (a common misconception), and to think of singers as primarily male. I was surprised by what I discovered in Spain: scores of women singers, from young girls to elderly matrons, whose riveting presence and passionate, intense voices, expressions and body language contrasted utterly with myths of machismo that promoted stereotypical images of southern Spanish women. As I began to reflect on the role of women in flamenco, on how these singers create their world, this took my research in a new direction. As I talked with aficionados in the United States and Spain, and as I explored the literature on flamenco, it became clear that women’s presence in cante flamenco had either been ignored, or considered quite minor and unimportant. I felt it was both valuable and necessary to examine the historical and contemporary contributions of women, in an effort to document the especially strong presence of women in flamenco song.

My awareness of this issue was heightened by events taking place while I lived in Spain from 1996–97. An anthology of women singers and composers, La Mujer en el Cante was recorded by prominent singer Carmen Linares and was released in summer of 1996. It received enormous praise, both for its high quality and for its recognition of important female singers. In the fall of 1996, the city of Seville declared the voice of legendary singer Pastora Pavon, La Niña de Los Peines cultural patrimony and began the task of collecting, archiving and digitally transferring all her existent seventy-eight recordings to compact disks. This was the first time in the history of Spain that a voice was being considered a cultural treasure, and it was noteworthy that is was the voice of a cantaora.

It seemed to me that the decade of the 1990s was bringing to light the prominence of women singers and that this was a cultural phenomenon that deserved some attention. The impression that “women’s time has come “in cante flamenco seems to be borne out by numerous press releases and concert reviews that have appeared in Spanish newspapers El Pais and ABC since the mid 1990s. Many important festivals have offered concerts of exclusively women singers, while in other recent concerts women singers have gotten top billing. Carlos Saura’s film Flamenco, released in 1995, foregrounds women singers and opens with a performance by veteran cantaora Paquera de Jerez. I was intrigued by the social changes that seemed to be enabling more women to be successful in ways not possible before, and to receive long over-due recognition. Conversations with a prominent flamenco producer in Seville corroborated my impressions, for this producer maintained that women represent the most authentic and best voices in cante flamenco today; indeed he expressed the opinion that it is women singers who are preserving and continuing the traditional cante. My book explores the significant role of women in cante flamenco, past and present in order to understand this role in the broader context of Spanish and Andalusian society and to highlight the role played by women in the innovations that are transforming flamenco today.

Sources

Looking back on my first year in Spain, it seems that I was constantly in motion, on buses and trains going between Seville, Jerez, Granada, other Andalusian towns and occasionally Madrid. I was after the big picture, to understand flamenco in its many forms and to see the differences from region to region. My research was characterized by frequent trips in which I got to know and to interview a great many people. Everywhere I went I talked with people, informally or in an interview context, and got a range of perspectives and opinions that gave me a good idea of the diversity of flamenco performance and the wide spectrum of opinions that characterize both its artists and its audience of devoted aficionados.

Early in my stay I contacted Flamenco recording producer Ricardo Pachón who lives in Seville. Pachón has worked with and promoted many of the Nuevo Flamenco (New Flamenco) artists, but at the same time he is a lover of the classic, more traditional forms. He offered me his own well-informed perspective on the flamenco scene, and also introduced me to many people who were very helpful and informative, among them singer El Lebrijano, flamenco scholar and journalist for newspaper El Pais Angel Alvarez Caballero, and Luis Clemente, a journalist in Seville who has authored several important books on genres of new flamenco. I attended several conferences on flamenco, the first in the Andalusian city of Ronda in July 1996 and the second in Madrid, as part of the program at Bellas Artes in November of that same year. Here I met performers, scholars, journalists and aficionados whose knowledge and insights enhanced my growing understanding of flamenco. This conference that took place in Ronda, El Flamenco explicado por los Flamencos, was especially interesting. Rather than flamenco scholars, it was performers like the late Pedro Bacán (a well-known guitarist) and his sister cantaora Inés who presented their personal perspectives on the direction that flamenco is taking at the end of the twentieth century. The conference was attended by a very knowledgeable group of journalists, aficionados and flamencólogos of various sorts, who engaged in lively, often heated discussions that were revealing of ideological dimensions characteristic of flamenco as a contested cultural phenomenon.

Interviews with the Cantaoras

Interviews with flamenco cantaoras formed the heart of my research. I conducted about twenty-five of these interviews between 1996–2001 with singers in Jerez, Seville, Granada and Madrid, who ranged in age from their early twenties to late sixties. These interviews were often arranged through the help of agencies who manage flamenco artists both in Seville and in Jerez and who connected me with singers. A few of the singers I met through personal introductions through mutual friends, while several I approached after concerts. In general though, I contacted them by telephone and was constantly surprised and always appreciative of their willingness to talk with me, to give of themselves, their time and energy to a complete stranger. The interviews consisted of an open-ended format in which I asked the cantaoras a similar set of questions and elicited their opinions on various issues. I did alter the format of my interviews somewhat in order to take into account the varied background and experiences of the individual singers.

Reflections on the Research

My year of research was a journey into the world of flamenco, a journey through the cities and towns of southern Spain and the old neighborhoods of Madrid, an intense experience of historic and contemporary Spain. I sought out numerous individuals whose generosity, graciousness and indefatigable Spanish sociability amazed and delighted me, and whose opinions and experiences informed my sense of what flamenco is, what it means to the people who perform it and to the people who are its dedicated audience. I elicited the perspectives of singers, guitarists, dancers, journalists, flamenco scholars and record producers. In addition to many hours spent at the Centro Andalúz de Flamenco and the Fundación Machado, I followed the discourse on flamenco closely as it appeared in the press and the media. This discourse was commented upon, discussed, supported and/or contested by those whom I interviewed.

The numerous performances I attended covered the broad range of flamenco performance: from intimate peñas to large concert venues and summer festivals; to performances of nuevo flamenco that were more like rock concerts than flamenco events; to the informal juergas (jam sessions) at La Carbonería in Seville and at flamenco bars in Madrid. Attendance at conferences and my participation in dance and guitar classes added a participatory dimension to my research. I returned to California with many books and recordings, video footage and treasured interviews with the women flamenco singers, journalists and scholars I had met. My recent visits to Spain in the summers of 1998 and 2001 provided additional interviews, information on the Bienal in September 1998, and recent Spanish publications on flamenco. My year in Spain in 1996, as well as fieldwork experiences in the summers of 1994, 1998 and 2001 have given me an in-depth perspective of the state of contemporary flamenco practices in Spain; on prevailing attitudes and opinions that inform the current discourse related to flamenco; and on the current efflorescence of women in flamenco performance.

Fieldwork Journey

Jerez

I began my year in Spain in the city of Jerez de la Frontera, situated about mid-way between the cities of Seville and Cádiz, which is the capital of the province on the Atlantic coast. I arrived in Jerez de la Frontera in March of 1996 and lived there until September of that year. The city of Jerez produces some of the world’s finest sherry and was historically dominated by a landed aristocracy of latifundistas, (large estate owners) known locally as señoritos. Jerez has also had a large and relatively assimilated gitano (gypsy) population, for at least several hundred years. Considered one of the few places in Spain where real assimilation of Gypsy and Andalusian population took place, whether by intermarriage or close, shared neighborhood living, many in Jerez pride themselves on the notion that there is less racism against gitanos in Jerez than exists in other parts of Spain. Such a perception is arguably more ideological than factual, for racist attitudes towards Gypsies do exist in Jerez; but it does reflect the belief of many. Certainly it is true that the populations of Gypsy and non Gypsy have mixed more often and more easily over the years and in so doing, have created an environment unique to Jerez. Regardless of the degree of mixing, Jerez today has a large population that refers to itself as gitano, a community on the one hand very conscious and proud of its identity, and on the other hand, very insular and closed to outsiders. Jerez is considered within flamenco circles to be one of the last strongholds of a particularly gitano sensibility, or aesthetic in

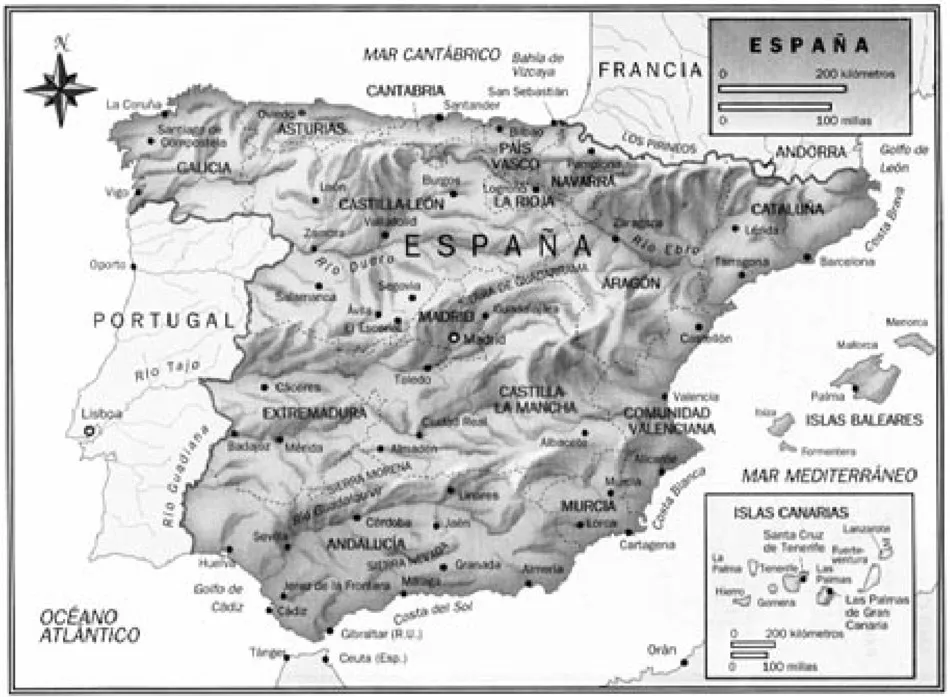

Figure 1.1. Map of Spain (Courtesy of Puntos de Partida, McGraw-Hill)

flamenco, and is known as one of the few places where flamenco can still be heard on a regular basis in fiestas in the homes of Gypsies.

The southern Andalusian triangle of cities: Seville, Jerez and Cádiz, are widely acknowledged as the “cuna” or cradle of flamenco cante. Each of these cities has a long history of flamenco that includes generations of performers within families; styles of cante distinguished from each other by stylistic traits; particular techniques or aesthetics of guitar style (toques) and a certain difficult to define quality referred to as aire, a term used by flamencos to denote a sound, a feeling, an identifiable style. I started out my flamenco journey in Jerez because I felt that flamenco was more accessible there. Small peñas, or social clubs, are numerous in Jerez and these offer weekly performances of flamenco, (primarily recitals of cante) in intimate and social settings. These peñas are free of admission charge in Jerez, for they are supported by the socios, or members. I was able to attend frequently and to hear a great deal of good cante on a regular basis there, ...