- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Tourism: A Community Approach (RLE Tourism)

About this book

Written in 1989 when the modern tourist industry had reached a crucial stage in its development, when increased mobility and affluence had led to more extensive and extravagant travel, and competition within the industry had intensified, this book is comprehensive examination of tourism development. The author provides a new perspective for its evaluation, and a suggested strategy for its continued development and evolution. He examines tourism from the viewpoint of destination areas and their aspirations, and recommends an ecological, community approach to developing and planning – one which encourages local initiative, local benefits, and a tourism product in harmony with the local environment and its people.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Tourism: A Community Approach (RLE Tourism) by Peter E Murphy,Peter Murphy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Hospitality, Travel & Tourism Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Section 1

Tourism and its significance

Tourism has become one of the world's major industries, but its emergence since the Second World War has caught many unaware and unprepared. Its revenue and development potential were soon recognized and pursued in the expansionary post-war economy, first by individual entrepreneurs and then governments. Consequently, the early emphasis was on growth and promotion rather than management and control. Tourism was viewed as being a “natural” renewable resource industry, with visitors portrayed as coming only to admire—not consume—the landscape, customs, and monuments of a destination area. However, as tourism grew in size and scope it became apparent that this industry, like others, competed for scarce resources and capital, and that its non-consumptive attributes did not necessarily prevent the erosion or alteration of attractions.

With the advent of mass tourism has come the reckoning and a belated recognition that to become a renewable resource industry tourism requires careful planning and management. Mass tourism is more than an increased volume of visitors, it has come to mean a myriad of manufacturing and service businesses which combine to offer a travel experience through scale economies and mass-merchandising. The heady days of rapid expansion tended to overshadow growing signs of negative environmental and social impacts, but as the competition for scarce resources grew more intense and the pressures of many visitors more evident, the problems of certain destinations and stress within the system could not be denied.

It is the purpose of this section to define the nature and scope of tourism, examine its evolution, and illustrate some of the major issues to be faced in maintaining and developing this industry. The text focuses on tourism problems and possible response strategies of destination areas in developed countries. Destinations are the interface between tourists and local communities, where the negative impacts and conflicts are felt most strongly and where remedial action will be required, whether it be physical or strategic planning.

This section concludes with the contention that the opportunities presented by the industry and the difficulties arising from its rapid development can best be examined and resolved through a community approach. Tourism has been examined traditionally in a systematic and aspatial manner, which has failed to give sufficient weight to the significance of its interactions and the importance of destination character. By focusing attention on the development of a community tourism product it is felt that several past research and planning weaknesses can be rectified. A community emphasis would temper the economic concerns with environmental and social considerations. The spatial impact of national policies and individual developments can be traced throughout a nation, thanks to the multi-scale interpretation and interlinkage of the term “community.” Finally, the importance of community survival, as a permanent home in which to live, work, and play, can be acknowledged in addition to the focus on its tourism potential.

1

Scope and nature of tourism

Size and importance

Tourism has grown from the pursuits of a privileged few to a mass movement of people, with the “urge to discover the unknown, to explore new and strange places, to seek changes in environment and to undergo new experiences” (Robinson 1976, xxi). During the post-war period tourism grew into a mass tourist industry. The number of international tourist arrivals rose from 25 million in 1950 to 183 million in 1970, an average growth rate of more than 10 percent (IUOTO 1970). Since 1973 the effect of fuel price increases has merely moderated the rate of expansion. According to estimates by the World Tourist Organization (WTO) international tourist arrivals in 1982 reached 280 million; but even more remarkable is the fact that these numbers reflect only the minor, and more easily measured, aspects of the tourism picture. Domestic tourism, which involves travel within one's own country, is more difficult to quantify but generally accounts for 75–80 percent of all tourism activity (Lundberg 1976, 9). According to the WTO there were over 2 billion domestic trips in 1981, representing a 240 percent increase over 1975 figures.

Such mass movements of people have been described as contemporary migration patterns. Migration can be seen as a response to stress, and Wolfe (1966) identifies three migration patterns in our society. The first, migration to the city, is a continuation of the nineteenth-century phenomenon, and, in the opinion of some, may have run its course in the developed world. The second, the journey to and from work, is a result of our large-scale urbanization and spatial separation of workplace and home. The third, recreational travel, is the newest migration and a function of the other two. It has been stimulated by the stress and uniformity of urban life and been accommodated by the standard of living and mobility provided by the same urban-economic system. Being the newest migration, recreational travel has experienced phenomenal growth rates—rates which cannot be maintained but which led to a major change in our lifestyles. Like the other migrations before it, tourism will peak and probably decline, but it will remain a part of our lives and probably change in form and emphasis in the process.

The multi-faceted nature of tourism, its various links with the manufacturing and retail sectors, and its numerous seasonal or unofficial businesses make it extremely difficult to assess its market size. One estimate, however, suggests that worldwide travel spending reached $488 billion in 1978 (Waters 1978, 5). This represented 6 percent of the world's 1978 Gross National Product (GNP), which in turn was the equivalent of West Germany's GNP at that time. A more recent WTO estimate places the 1981 expenditure on world travel at $919 billion. The growth in tourism revenues has been substantial since the Second World War, but as in the case of visitor volumes the rate of growth has slowed since the oil crisis and inflation of the 1970s. When calculated in real terms the revenue increases have declined from the post-war region of 10 percent a year to 3 percent, but it is still growth nevertheless (OECD 1980).

Despite the short-term setbacks of the energy crises and recessions of the late 1970s and early 1980s, tourism is seen as a growth industry of the future. Toffler's Future Shock (1971) described the modem businessman and vacation traveler as the “new nomads” and foresaw:

a revolutionary expansion of certain industries where sole output consists not of manufactured goods, nor even of ordinary services, but of pre-programmed “experiences”. The experience industry could turn out to be one of the pillars of super-industrialism, the very foundation, in fact, of the post-service economy. (Toffler 1971, 208)

His more recent work, The Third Wave (1981), predicted the breakup of industrial society, as we know it, through a process of “demassification,” breaking up large units of government and industry into more individual and flexible lifestyles. Among the changes which will relate to tourism he foresaw:

Large numbers of workers already do paid work for what averages out to only three or four days a week, or they take six months or a year off to pursue educational or recreational goals. This pattern may well grow as two-paycheck households multiply. (Toffler 1981, 277)

The appeal of this industry for the transitory period from an industrial society to whatever future awaits us is not limited to futurologists. Nations, such as Spain and Austria, have based much of their post-war development on growth in their tourism sectors. Earnings from the international tourist account contributed a significant portion of their export earnings in 1977, 22.5 percent for Spain and 21.7 percent for Austria. This compared with a European Community average of 4.7 percent (British Tourist Authority 1981, 13), and created a major source of “hard” currency for other development projects. Furthermore, in a time of growing automation and rising unemployment, tourism as a labor-intensive industry has proved to be both economically and politically appealing. As the then Prime Minister of England, James Callaghan, once described the situation:

Now new plants in manufacturing and new investment and new methods bring greater efficiency but it does not necessarily mean more jobs, and for this reason, we need to look at the service industries of which tourism is a notable example as an additional and important source of income and work (English Tourist Board 1977, 5)

The development of mass tourism has created a powerful and influential recreational travel industry. For example, in England it is estimated that “some l½ million jobs were generated either directly or indirectly by tourism in 1975, equivalent to about 6 percent of total employment” (English Tourist Board 1978a, 4). In Canada tourism is promoted as big business which is important to all Canadians, because it employs one out often workers and is the seventh largest earner of foreign exchange (CGOT 1982). In the United States the tourism industry grosses an estimated $105 billion annually and employs over 5 million workers (Pizam and Pokela 1983). With such impressive statistics and employment opportunities it is little wonder that this industry has become a powerful political lobby. In Britain and Canada the industry has received generous development grants, and in Canada a private sector task force is cooperating with the government to produce the first national tourism plan (Powell 1978).

At the international level the United Nations has noted the economic and social significance of this growth industry. A 1979 report stated that tourism was bigger business than iron and steel or armaments, and that about 500 million workers and their families throughout the world were entitled to paid vacations. While recognizing the beneficial economic effects tourism can bring to national economies and world trade, the United Nations Manila Conference on World Tourism noted that its potential goes beyond just economic considerations. The first declaration of that Conference read:

Tourism is considered an activity essential to the life of nations because of its direct effects on the social, cultural, educational and economic sectors of national societies and their international relations. (UN 1981, 5)

Since tourism is now an integral part of modem societies, its study and analysis becomes imperative if its potential economic and social benefits are to be maximized and developed in a manner consistent with society's goals. The growth of tourism has converted many communities into destination areas, either as major resorts or as temporary stop-overs for travelers. The impact of the industry and its local issues will vary according to its magnitude and relative importance, but in every case politicians, businessmen, and residents are recognizing they cannot ignore tourism if they wish to benefit from it.

Definitions

The raison d’être of the industry is the tourist, so all development and planning must be predicated on the understanding of who this person is, if it is to succeed. The term “tourist” is derived from the word “tour,” meaning, according to Webster's Dictionary, “a journey at which one returns to the starting point; a circular trip usually for business, pleasure or education during which various places are visited and for which an itinerary is usually planned.” As this definition indicates, there are several motives for travel, each requiring its own facilities and having a different impact. Thus, government agencies in search of a comprehensive definition of tourist, and one which will facilitate the measurement of this activity, have resorted to the more general term of ‘Visitor.” The definition most widely recognized and used is that produced by the 1963 United Nations Conference on Travel and Tourism in Rome, which was adopted by the International Union of Official Travel Organizations (IUOTO) in 1968. It states that a visitor is:

any person visiting a country other than that in which he has his usual place of residence, for any reason other than following an occupation remunerated from within the country visited.

Thus, tourism is concerned with all travelers visiting foreign parts, whether it be for pleasure, business, or a combination of the two. The only exception is someone who is setting up a new residence in a foreign country and will be earning a salary and paying taxes in this new country. The IUOTO definition was intended for international travel but it can accommodate domestic tourism by substituting region for country.

Visitors have been subdivided further into two categories to assist the measurement of tourist traffic and the assessment of its economic impact.

(1) Tourists—who are visitors making at least one overnight stop in a country or region and staying for at least 24 hours.

(2) Excursionists—who are visitors that do not make an overnight stop, but pass through the country or region. An excursionist stays for less than 24 hours, and includes day-trippers and people on cruises.

This division has the practical value of using overnight accommodation records (registrations) as the basic source of tourist information, which can be used in conjunction with border crossing records if international movement is involved. By focusing on the accommodation sector of the industry, however, it also produces conservative estimates of the travel picture. There is no way to count overnight visits with relatives and friends and it is often impossible to obtain accurate records from small or temporary establishments like guest houses and farms.

The excursionist, or day-tripper, can be viewed as a special tourist. Such a person visits a destination for a day or spends some time there while passing through as part of a tour. In either case, he or she is a visitor, spending time and money while utilizing space and facilities in the destination area.

Types of tourist

There are as many types of tourist as there are motives for travel. Each type makes different demands of a destination, and has its own particular impacts. Business travel can range from convention and trade fair meetings to vacations that include self-advancement courses or permit the traveler to update certain areas of his profession. Leisure travel can incorporate activity packages where the tourist learns a new sports skill or craft, as well as developing a tan. The impact of tourists’ demands will vary according to the demands they place on a destination's physical and human resources.

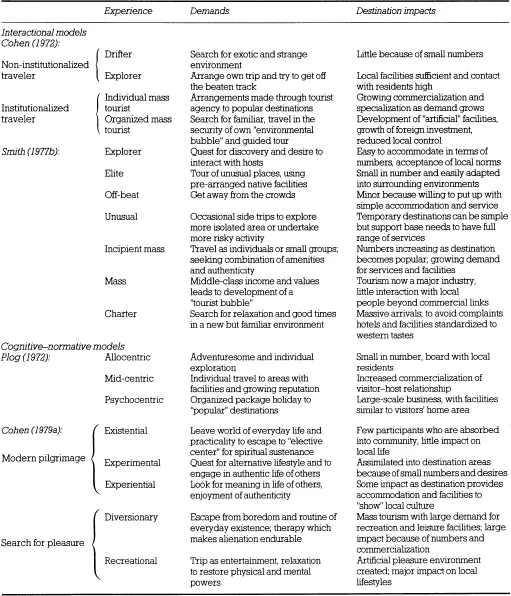

Tourist typologies can be grouped into two general categories (Table 1). Interactional types emphasize the manner of interaction between visitors and destination areas, whereas the cognitive-normative models stress the motivations behind travel. Both approaches indicate the strong links between visitor expectations-motivations and the structure of destination areas. Thus it can be seen immediately that no destination appeals to all tourists and each can develop its own segment of the tourism market.

Among the interaction models are those of Cohen (1972) and Smith (1977b). Cohen classified tourists according to the degree they seek familiar or strange settings and whether or not they were willing to be institutionalized (organized) in their travel. Smith's more detailed breakdown incorporates recent market developments such as the unorganized “hippie treks” to Nepal and the social implications of a highly structured charter business. Smith, like Cohen, views explorers and elite travelers as having little impact upon indigenous cultures. Their small number requires little in the way of special accommodation, and their desire to gain insight into local customs is aided by a sympathetic attitude to the local way of life. In contrast, the charter tourists travel in their own environmental bubble, viewing everything from the security of their pre-paid and price-guaranteed package tour. To accommodate the large numbers and organizational structure of charters a community must become commercial in its dealings with tourists, and often needs to import foreign capital and expertise.

In contrast to the interaction models which focus on the market characteristics and symptoms of travel, the cognitive-normative models attempt to reveal the causes of travel. Plog (1972) and Cohen (1979a) both look at the sociological concept of “center,” which considers that every society possesses a center representing the charismatic nexus of its supreme, ultimate moral values. Plog develops a polar continuum consisting of those who differ from the normal (centric) values of society and follow their independent vacation desires (allocentrics), and those who conform to society's norms and values and thus become part of the mass market of tourism (psychocentrics).

Table 1 Tourist typologies

Plog suggests that tourist destinations are attractive to different types of visitors as they evolve from untouched discoveries to popular resorts. A community can enter the tourism business with the arrival of a small number of adventurous allocentrics, but their impact would be small because no special facilities would be desired or requir...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Figures

- Tables

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Section 1 Tourism and its significance

- Section 2 The environment and accessibility

- Section 3 Economic and business

- Section 4 Society and culture

- Section 5 Planning and management

- References

- Name index

- Subject index