eBook - ePub

Marketing in the Tourism Industry (RLE Tourism)

The Promotion of Destination Regions

- 248 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Marketing in the Tourism Industry (RLE Tourism)

The Promotion of Destination Regions

About this book

This book examines how different sections of the tourism industry attempt to reach their markets. A wide range of distinctive forms of holiday are considered, and the influence their characteristics have on how they are marketed is discussed. But the approach is also comparative, and the relative success each area of the industry has in reaching its market is evaluated.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Marketing in the Tourism Industry (RLE Tourism) by Brian Goodall,Gregory Ashworth in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Hospitality, Travel & Tourism Industry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

HOW TOURISTS CHOOSE THEIR HOLIDAYS: AN ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK

THE HOLIDAY HABIT

Taking holidays is major international business. The market is world-wide and tourism is an international growth industry. Increased real disposable income, longer holidays with pay, improved opportunities for mobility, better education and wider dissemination of information have all contributed towards changing people's attitudes about taking their holidays away from home. First robotization in the factory and now computerization in the office have so standardized work that, for those in employment, there is an increased need for periods away from humdrum everyday routine.

Since the beginning of the 1960s world tourism, as measured by international tourist arrivals, has grown at a rate of over 6 per cent each year and the underlying trend, despite some instability in the mid-1980s, allows continued growth in demand for holidays to be forecast.

A holiday is seen by the individual and the family as a most desirable product. Once indulged in the holiday habit enjoys a high ranking in people's future budgets: even an increasing consumer priority. Holidays are a mainstay of behaviour patterns in advanced western societies and any survey of holiday intentions will lend support to the importance attached to holiday-making.

Sustained growth in aggregate tourist flows masks variation in the types of holidays taken and destinations visited, the latter responding particularly to floating exchange rates and oscillating fuel prices. Tourism is a highly competitive industry and the message conveyed to the potential holiday-maker is one of increased choice. More destinations, in more countries, are available; a wider variety of holiday types, especially activity ones, are on offer; whilst travel, accommodation and timing arrangements are now sufficiently flexible for individual tailor-made holidays. The potential tourist appears spoilt for choice!

Tourists have high expectations of their forthcoming holiday and also demand value for money. Given such choice between numerous competing destinations they will favour those holidays which offer the fullest realisation of their expectations. But how do tourists choose their holiday?

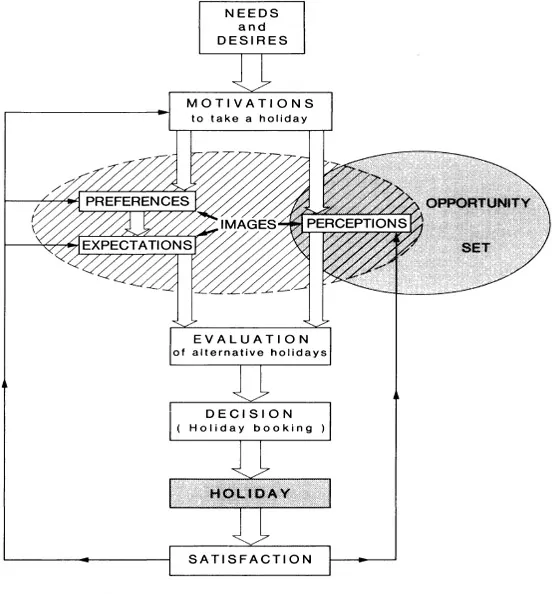

THE HOLIDAY SELECTION PROCESS

A holiday is a high-risk purchase because, unlike most other retail purchases, the tourist can neither directly observe what is being bought, nor try it out inexpensively. Previous experience of the holiday-maker or his acquaintances is similarly a poor predictor of future satisfaction as the conditions determining success are specific in time and space. Holiday planning (whether and where to go) takes place over a long time, although the planning horizon differs between types of tourist. This planning and anticipation, which in Western Europe is in full swing by January for holidays to be taken in the summer, is an important aspect of the experience itself and a potent source of satisfaction. This implies, as conceptualised in Fig. 1.1, a process which is systematic and sequential. Such conceptualisation, however, acknowledges the importance of a behavioural perspective in understanding how people make holiday decisions. At best the tourist is a satisficer acting within implicit and explicit constraints of an uncertain environment.

Motivations

For any individual the decision to take a holiday stems from both needs and desires. On the one hand needs are intrinsic, an innate condition arising from a lack of something necessary to the individual's well-being, and reflect emotional, spiritual and physical drives. On the other hand desires are extrinsic, a feeling that the individual would get pleasure or satisfaction from doing something, and are acquired through and dependent on the value system prevalent in society. Together, needs and desires determine motivations, i.e. definite and positive inclinations to do something. Motivations for pleasure travel contain push factors related to the home environment, such as break from work, escape from routine, or respite from everyday worries, and pull factors related to the stimulus of new places and the attractions of destinations. Motivations have been classified (see, for example, Mathieson & Wall, 1982; Murphy, 1985) as (i) physical (or physiological), e.g. search for relaxation, health, sport, or challenge; (ii) cultural, i.e. the wish to learn about foreign places; (iii) social, e.g. the visits made to friends and relatives, or for prestige or status reasons; and (iv) fantasy (or personal), i.e. escape from present reality. Such motivations, weighed against other circumstances affecting the individual, influence the propensity to take a holiday but not the decision to go to a particular holiday destination.

Images

Having decided to take a holiday what influences the individual's choice of destination? To convert motivations into a holiday trip requires the identification of the tourist's preferences and a knowledge of holiday opportunities. Mental images are the basis of the evaluation or selection process (see dashed ellipse in Fig. 1.1). All activities and experiences are given mental ratings, good or bad, and each individual, given their personal likes and dislikes, has a preferential image of their ideal holiday. This conditions their expectations, setting an aspiration level or evaluative image, against which actual holiday opportunities are compared.

Figure 1.1: The tourist's holiday decision

An individual's perception of holiday destinations, i.e. their travel awareness, is conditioned by the information available. At any given time each individual, as shown in Fig. 1.1, is aware of only part of the total holiday opportunity set. From information available regarding this perceived opportunity set the potential holiday-maker constructs a naive (or factua1) image of each destination. That information may be derived from formal sources, e.g. travel agents, holiday brochures, or informal sources, e.g. friends. Amongst the perceived opportunity set will be several destinations which appear to meet the individual's holiday expectations and these must be evaluated further, according to criteria such as family, home and work circumstances; value for money; and destination attractions. This combination of holiday trip features and destination resources constitute the basis for holiday selection within the constraints imposed by generation point characteristics. Having identified the holiday in a particular destination which appears to exceed the aspiration level by the greatest amount the tourist makes a booking.

Between booking and departure there is an anticipatory phase during which an individual's expectations and perceptions may be refined as more information is obtained. Then comes the holiday, which may or may not come up to expectation. The tourist enjoys a certain level of satisfaction from the holiday and this induces feedback effects (see Fig. 1.1) on motivations, preferences, expectations and perceptions of a reinforcing nature, where a highly satisfactory holiday experience, or of an adaptive or modifying nature, where the experience, in part or overall, was not up to expectation. Thus, at any point in time, each tourist has a certain accumulation of mental images about a variety of holiday experiences in a number of destinations.

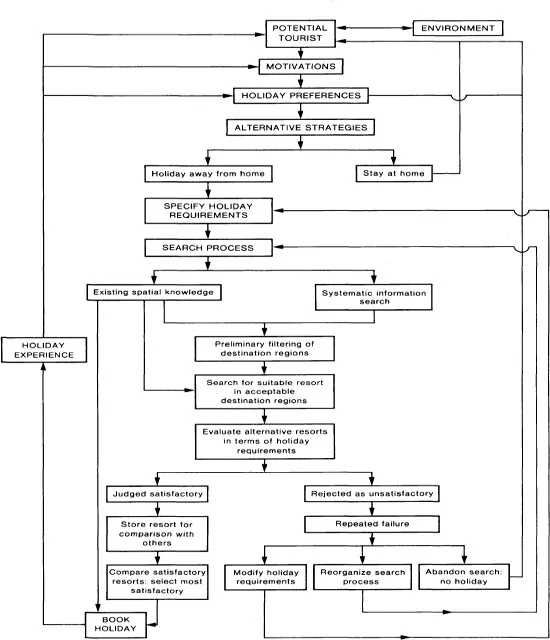

CHOICE OF RESORT

Tourists vary not only in respect to their accumulated knowledge of holiday experiences and opportunities but also in terms of the extent to which their choice of holiday destination is a systematised process. A behavioural, rather than a normative economic perspective is therefore required to understand how people reach decisions and act upon their experiences (see also Mathieson & Wall, 1982). Thus the tourist's annual holiday choice may be conceptualised in more detail as a search process (see Fig. 1.2) which acknowledges tourists differ in their abilities to obtain and use information about holiday opportunities.

Figure 1.2: The tourist's annual holiday search process

The potential tourist interacts with an environment (comprising nested behavioural, perceptual, operational and phenomenal elements) which determines not only the holiday opportunities available but also the tourist's motivations and preferences regarding holiday-making. Once the decision to go away on holiday, rather than stay at home, has been made the requirements of the holiday must be specified: these will depend on factors such as whether the tourist will be accompanied by family or friends, the type of holiday sought is activity- or touring-based or is a traditional seaside one.

The search process

The tourists then begin a search process to find the holiday which best matches their requirements within the limits imposed by what they can afford and the timing of their other commitments. Considerable variety exists in the search behaviour of potential tourists with planning horizons and preparations differing markedly between types of tourist. At one extreme is the ‘impulse buyer’ who, walking along the high street, is attracted by a ‘cut-price immediate departure package’ advertised in the travel agent's window. This tourist makes up his mind on the spot, enters the travel agency, books up, and is away on holiday in a matter of days. Here the planning horizon is at its shortest and the decision is obviously made on the basis of existing spatial knowledge. At the other extreme is the ‘meticulous planner’ – the tourist who obtains up-to-date information from travel agents, tour operators’ brochures, tourist boards and similar organisations and compares prices in detail before putting together a tailor-made package. Here the planning horizon approaches a full year with advance preparations for next year's holiday beginning as soon as the previous year's is completed. In this case once a firm booking is made preparations continue in respect of obtaining additional information on the attraction of the selected resort, e.g. opening times of historic houses or safari parks, routes for scenic drives or excursions. In between these two extremes holiday search behaviour involves an enormous variety of combinations of existing spatial knowledge and specific information gathering.

Novelty is an important requirement of a holiday destination but for many would-be tourists this may be offset by the worry and uncertainty of coping with the unfamiliar. This balance of opposing requirements of novelty and security is seen as especially relevant to determining where people are prepared to go abroad (Social & Community Planning Research, 1972). Thus a preliminary filtering of destination regions/countries is made by many tourists in which their existing spatial knowledge is important in ruling out some destination areas because ‘people there are reputed to be unfriendly’ , ‘the food is disliked’, ‘there are bound to be language difficulties’, etc. Where existing knowledge comprises good previous holiday experiences the potential tourist may by-pass this first stage and proceed directly to the search for a suitable resort in an acceptable destination area. Whilst there is a degree of repeat visiting to countries, there is evidence that tourists display greater originality when it comes to choosing resorts within these countries (Carrick, 1985). For some tourists an earlier holiday decision, such as the purchase of a second home or time-share interest, may condition subsequent holidays to the extent that they appear habitual (unless, for example, second-home owners and time-sharers participate in exchange schemes).

Evaluation of alternatives

Returning to Fig. 1.2 and the search for a suitable resort: each resort considered by potential tourists must be evaluated against their detailed holiday requirements. Where the first resort which meets these requirements is selected the tourist is acting very much as a satisficer (although this should also be viewed in terms of the propensity of the tourist to visit new resorts on each vacation). Where several resorts which fulfil the requirements’ test are stored for comparison the tourist is practicing a form of optimizing behaviour within a context of bounded rationality, the assumption being that the resort selected is the one which it is anticipated will best satisfy the tourist's requirements. If the potential tourists are unable to find an acceptable resort then they must consider modifying their holiday requirements and/or reorganising their search process: failing that they abandon the search and do not go away on holiday.

It must be emphasized that the search process undertaken by a potential tourist seeking a new destination to visit is restricted to obtaining information in a secondary form: namely, tour operators’ brochures, official guide books, tourist board promotional literature, advice from travel agents, friends’ comments about their holidays. Site visits, which are an integral part of search processes in the case of house purchase or factory location, are not made by the potential tourist: at least, that is, not until he/she actually goes on holiday – by then the commitment has already been made. If the holiday turns out to be less than satisfactory it becomes part of the tourist's accumulated experience which will influence motivations, preferences and requirements for subsequent holidays. However, it has been argued (Gitelson & Crompton, 1983) that systematic information search of external sources is used much more frequently in making holiday and travel-related decisions than in consumer decisions to purchase most other types of product. This reflects, of course, the tourist's propensity to visit new destinations on each holiday. Main holidays taken by tourists tend to be better planned than second or subsidiary ones (Marketing Sciences, 1982).

Choice of holiday resorts and the extent of holiday travel depend, for most tourists, as much on the amount of free time people have and when it occurs and what they can afford to spend as it does on the intrinsic attractiveness of the special facilities and natural resources of the resorts. The point of decision may not always be as precise as conceptualised and is made in terms of an image efficiency or anticipated experience criterion (kept within the tourist's time, money and other limits)(Gunn, 1972). Where prices are comparable image is the decisive factor in holiday choice.

So far the analysis has assumed that choice of holiday resort was a package involving travel, accommodation and, probably, excursions. This certainly holds true for inclusive tours abroad but there is a clear difference in the way people regard accommodation’ as a component of a holiday abroad compared to a home country one (Marketing Sciences, 1982). For holidays abroad accommodation is seen as part of the total package but for a home country holiday the choice of accommodation will be a separate consideration in which economic factors, rather than preference, govern that choice. There is also a preference, especially in the case of home country holidays, for destinations that can be reached inside a day's travel (Social & Community Planning Research, 1972).

HOLIDAY SELECTION AS AN ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK

Participation in tourism is voluntary and personal. Destination areas are competing to attract holiday-makers and the discussion above highlights the importance of the would-be tourists’ mental images of possible holiday destinations, i.e. tourism products. Likewise, marketing and consumer researchers frequently stress the role of image in consumer product preference (Hunt, 1975). Although such images represent, in the case of holiday-making a very personal, composite view of a destination's tourism potential the images held by any person are not static, unchanging. At any given time a person possesses a certain accumulation of images about a great number of holiday experiences, some personal but many second-hand. These images, for each person, will be modified and added to with each additional experience and by further exposure to a variety of information sources.

The implications for tourist destinaton areas are clear. First, unless a given destination figures amongst a would-be tourist's current set of mental images it has no chance of being selected as the holiday base. Second, where it does figure in the tourist's image set a very positive image of that destination must be projected in the tourist's mind for it to be selected in preference to an alternative. Third, where the tourist is successfully enticed to a...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Title Page

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- Contributors

- Preface

- 1. HOW TOURISTS CHOOSE THEIR HOLIDAYS: AN ANALYTICAL FRAMEWORK

- 2. CHANGING PATTERNS AND STRUCTURE OF EUROPEAN TOURISM

- 3. THE DEVELOPMENT OF TOURISM IN THE LEAST DEVELOPED COUNTRIES

- 4. THE ROLE OF TRAVEL AGENT AND TOUR OPERATOR

- 5. THE ROLE OF THE TOURIST BOARD

- 6. PLANNING OF TOURIST ROUTES: THE GREEN COAST ROAD IN THE NORTHERN NETHERLANDS

- 7. RECREATIONAL DEVELOPMENTS IN GRAVEL WORKINGS: THE LIMBURG EXPERIENCE

- 8. THE ECONOMIC EFFECTS ON DESTINATION AREAS OF FOREIGN INVOLVEMENT IN THE TOURISM INDUSTRY: A SPANISH APPLICATION

- 9. THE IMAGE OF DESTINATION REGIONS: THEORETICAL AND EMPIRICAL ASPECTS

- 10. MARKETING THE HISTORIC CITY FOR TOURISM

- 11. DEVELOPMENTS IN THE PROMOTION OF MAJOR SEASIDE RESORTS: HOW TO EFFECT A TRANSITION BY REALLY MAKING AN EFFORT

- 12. TOURISM DEVELOPMENT PLANNING IN LANGUEDOC: LE MISSION IMPOSSIBLE?

- 13.CHANGING TOURISM REQUIRES A DIFFERENT MANAGEMENT APPROACH

- 14.TOURIST IMAGES: MARKETING CONSIDERATIONS

- Index