![]()

Chapter 1

CAN PLACES BE SOLD FOR TOURISM?

Gregory Ashworth and Henk Voogd

INTRODUCTION

Can places be sold for tourism? This question appears to have a self-evident positive answer. Ever since Leif Ericson recruited settlers for his ‘Green’ land, places have been promoted by means of the projection of favourable images to a potential market of users by those who have an interest in attracting them. More recently, however, the idea of selling places, or geographical marketing (as defined by Ashworth & Voogd, 1987b), has received growing attention by public authority planners and decision-makers as a form of place management.

Place marketing, and especially place promotion, accounts for an increasing share of both municipal budgets and attention from academics from a number of disciplines, with the new, or at least newly respectable, study of ‘Marketing Science’ in the vanguard. ‘Selling places’ (cf. Burgess, 1975) has become an accepted part of the function of public authority place management, although not without the misgivings of many (Clarke, 1986). Places are ‘sold’ in a large number of potential consumer markets and by private as well as public sector organisations. The concern of this chapter and many chapters in this book, however, is the ‘selling’ of tourist destinations by public agencies with broader civic responsibilities. It is in this area that the difficulties of transferring and adapting ideas and techniques developed for the sale of goods and services by commercial firms for measurable intermediate financial profit, become most apparent.

The aim of this chapter is to address the theoretical and conceptual assumptions implicit in such approaches. It begins with a brief empirical exercise, in which the obvious relationship between promotional activities and tourist visitors is illustrated. The possible theoretical consequences of this relationship will be subsequently discussed. Attention is paid to marketing planning as a kind of public sector place management and to the concept of a tourism destination as a marketable product. In addition, the question will be raised whether a tourist can be compared with a ‘place customer’. Finally, the central importance of the price mechanism within marketing, including marketing tourism places, is raised.

TOURISM PROMOTION AND TOURIST USE

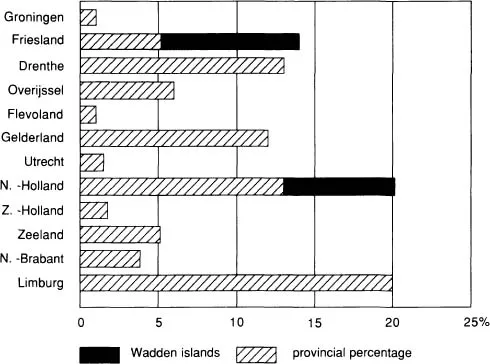

Marketing, and especially its promotional aspects, is based on the assumption that there is some relationship between the amount of promotion and the number of visitors (or ‘customers’). The same assumption holds for place marketing. It is therefore interesting to investigate this relationship in more detail. For this reason the advertisements in the weekend editions of three Dutch national newspapers (viz. De Volkskrant, Trouw, and Parool) have been examined over a certain period (i.e. from 9 July to 17 September 1988) in order to obtain an idea about the differences in promotional activities towards domestic tourists between the Dutch provinces. In total 1,773 advertisements were counted which addressed one or more aspects of the tourism ‘product’ of a province and/or town or region within the province. The majority of the advertisements was devoted to the promotion of tourist accommodation (e.g. hotels, apartments, camp sites): among other subjects were the promotion of horse riding, sailing and sea fishing opportunities.

The results are presented in Fig. 1.1. It shows that the highest percentage of advertisements relate to places in the provinces of North Holland and Limburg, followed by Friesland and Drenthe. However, the high figures for North Holland and Friesland are to a considerable extent determined by the Wadden Islands. North Holland includes the island of Texel, whereas Vlieland, Terschelling, Ameland and Schiermonnikoog belong to the province of Friesland.

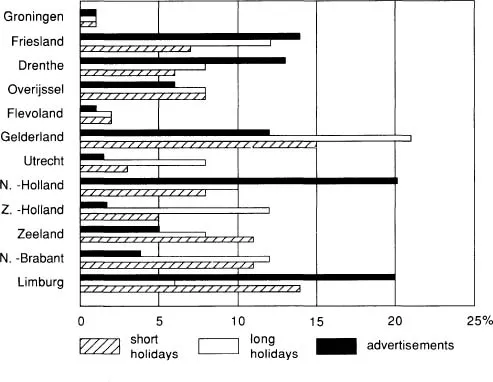

It is interesting to compare this level of promotional activity with some figures about the tourists that visit the various provinces. This is done in Fig. 1.2, which includes both the percentage of tourism advertisements and the rovincial percentage of short and long holidays for 1985 (Central Bureau of Statistics, 1987). This illustrates that there is some relationship between promotion and number of visitors. The provinces with hardly any advertisements (e.g. Groningen, Flevoland) attract relatively few tourists, whereas the provinces with more advertisements also have more people for a short holiday (Limburg) or a long holiday (Gelderland, Friesland). However, it is also obvious from Fig. 1.2 that no one-to-one relationship exists: for instance, the many advertisements for North Holland are not entirely reflected by the number of tourists in 1985.

Figure 1.1:Tourism advertisements in weekend editions of Dutch national newspapers, 9 July – 17 Sept. 1988

On the basis of Fig. 1.2, we may distinguish four provinces with a higher ‘advertisement rate’ than tourist visitors: Friesland, Drenthe, North Holland and Limburg. Seven provinces show the opposite picture, viz. relatively less advertisements and a higher ‘tourist rate’: Overijssel, Flevoland, Gelderland, Utrecht, South Holland, Zeeland and North Brabant.

Figure 1.2:Tourism advertisements compared with long and short holidays in 1985 by province

Of course, the present data do not allow more detailed conclusions. This rough exercise is only meant as an incentive to a further study of tourist behaviour in relation to place promotion, and vice versa, but it does demonstrate that the assumption of even simple relationships needs further examination. In particular the simple question is posed as to. why some provinces appear to be more effective in their marketing activities than others. Such questions are addressed by many of the subsequent chapters in this book.

MARKET PLANNING AS PUBLIC SECTOR PLACE MANAGEMENT

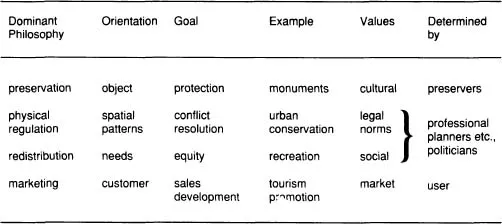

Places have been managed on the basis of a large number of different philosophies, in pursuit of a wide variety of goals, but in order to emphasise some of the differences in approach, three such philosophies, relevant to tourism and commonly found among public local authorities, are compared in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1:Some public authority planning philosophies

The implications of a marketing philosophy can be best appreciated if it is compared with a cursory summary of some other possible approaches to tourism planning. A preservationist philosophy regards the protection of the natural and built environment from threats to it as a public trust. The place as a tourism resource, whether preserved and renovated historic city or protected landscape, is treated defensively and success is measured in terms of its maintenance. Most public physical planning has concentrated on places as spatial patterns of morphological forms and interacting functions, which must be channelled and controlled so that conflicts can be avoided or a desirable balance between functions achieved. Tourism is, in this case, one function within the multifunctional place to be managed on the basis of professionally determined norms and political decisions about the role it should play in the wider spatial setting for the attainment of municipal goals.

The adoption of the last listed public planning philosophy, viz. ‘marketing’, is, in a superficial sense, deceptively easy to accomplish. At the shallowest level it is merely a matter of substituting a new terminology and renaming the various procedures of the planning process. Tourism supply becomes the tourism product to be ‘positioned’ in relation to competing products, demand becomes the customers, which need ‘segmentation’ according to product purchasing behaviour, and management becomes market planning undertaken in a ‘development’ or ‘promotion’ department. At a deeper level the transfer is attained by regarding marketing as the adoption of a new set of planning procedures that claim to be customer or client orientated (see Ashworth & Voogd, 1987b, or Hebestreit, 1977, for what amounts to a procedural manual for tourism marketing). Some of the most obvious examples in tourism are to be found in the British Tourism Development Action Programmes or the, in many ways very similar, Dutch Tourism and Recreation Development Plans (Kerstens, 1983; Ashworth & Bergsma, 1987). In both of these ‘feasibility’ studies, existing and potential demand conditions are compared with ‘product analyses’, i.e. inventories of the facilities and attractions of places, in the light of such demands and in comparison with competing places. Deficiencies are thus highlighted and dealt with by a mixture of new investments on the supply side and market promotion on the demand side.

Whether such tourism plans are just ‘old wine in new bottles’, they regard market planning as a set of procedures. A further and usually much more difficult step for many public authorities is to substitute market responsiveness for what could be termed the professional normative responses, which are intrinsic to the nature of bureaucracies. In particular much of the land use planning developed in post-war Western Europe (Burtenshaw et al., 1981) attempts to manage tourism by appeals to norms derived from contemporary professional conventional wisdom, and enshrined in legislation or ‘good practice’ so as to determine ‘carrying capacities’, ‘conforming land uses’, ‘acceptable functional mixes’ and the like. Market planning as an organisational philosophy does not so much arrive at different answers to these sorts of problems of place management as largely ignore the questions and substitute quite different ones, and equally important, quite different methods of obtaining answers for them. It is these differences that will be examined in more detail below.

IS A TOURISM DESTINATION A PRODUCT?

Tourism destinations can undoubtedly be treated as products. They are logically the point of consumption of the complex of activities that comprises the tourism experience and are ultimately what is sold by place promotion agencies on the tourism market. The potential holidaymaker in that sense is buying at the travel agents the product ‘Benidorm’ in preference to one labelled ‘Sitges’, and it makes no difference to this definition that only a selected portion of the town, a particular set of facilities and services, is being purchased. As with a more easily delimitable good or service the attributes purchased by the customer do not have to amount to a full technical inventory of all possible attributes of the object on sale. The National Marketing Plan for Historic Environments, produced by the Netherlands Research Institute for Tourism (1988), for example treats historic artefacts and associations as important tourism products and Kirby (1985) argues that leisure as a whole could be treated as a ‘commodity’.

There are, however, a number of fundamental differences between a place as a tourism destination and a marketable good or service purchased directly by customers of the tourism industry, such as the hire of hotel space or purchase of souvenirs. Jansen-Verbeke (1988) combines these two product definitions in her concept of the Tourist Recreation Product (TRP). Such a TRP is treated simultaneously in the selected worked examples, as both the inner city as a whole and also the ‘commodities’ of which it is composed. Four points need further investigation:

(i) The problem of defining and subsequently delimiting a place as a product has been raised previously (see Ashworth's 1985 discussion of towns as tourism resources), but such difficulties as defining, delimiting and thus planning for the tourist's Benidorm as opposed to other varieties of the same product, or more accurately other products of the same name, are practical rather than conceptual and are thus open to solutions of working practice, not relevant to the discussion here. However, the series of studies of the Tourist-Historic city (Ashworth & de Haan, 1986) which attempted to define and delimit on the ground the historic attractions of the city as defined by use in tourism, revealed a particular difficulty. Places, in this case tourism towns, both contain tourism facilities and attractions and simultaneously are such a facility and an attraction. The place is both the product and the container of an assemblage of products. This in turn has implications for the promotion and management of such places.

(ii) The distinction mentioned above leads to two further qualities of places as products which have a particular influence upon how such places can be marketed. The tourism product consumed at a particular place is assembled from the variety of services and experiences obtainable there, but this assembly is conducted largely by the consumer rather than the producer. Even when some important items are sold together in packages determined by the tourism producers or intermediaries, each individual holiday will still largely consist of a consumer selection of products which will be necessarily unique. This situation is quite different from that found in the marketing of most goods and services, whether in the private or public sector. Clearly, a consequence of this situation is that the place product is marketed by destination agencies without any clear idea of the nature of the product being consumed.

(iii) Another consequence of the delimitation problem is that of spatial scale, a characteristic possessed by places but not by other types of product. A place is inevitably one component in a hierarchy of spatial scales. This is more than the inevitable parochial viewpoint of a geographer accustomed to hierarchical spatial modelling: it is central to the nature of the tourism product and how it is marketed. The potential holidaymaker buying Benidorm, may equally be purchasing other levels in the hierarchy, the hotel and its grounds, the tourism sea front zone, the Costa Brava, Spain and even the Mediterranean. One conclusion of the study of the Languedoc coast (see Chp.9) is that there are major scale discrepancies in the definition of the product by those concerned with shaping, marketing and managing it. Here, as in many such tourism areas, the choice of scale for the definition of the tourism product is determined by the nature of local government boundaries at different scales. Thus arbitrary political boundaries, and the division of public functions within the local government hierarchy, assume a greater significance in shaping the product than the intrinsic characteristics of the place or the perceptions and behaviour of the customer. Are national, regional and local tourism promotion agencies selling different products or parts of the same products? Would a differently structured hierarchy create a different product?

(iv) Finally, and probably of greatest significance to the introduction of marketing techniques into local authority planning: places are multi-sold. There are few parallels in the commercial marketing of goods and services to the situation in place marketing, where precisely the same physical space, and in practice much the same facilities and attributes of that space, are sold simultaneously to different groups of customers for different purposes. The earlier reference to the analysis of the concept of the historic city, for instance, draws the clear distinction between the sale of facilities in such a city (visits to attractions, museums...