BOOK THE SECOND.

CHAPTER I.

Examination of the Textile Fibres,-Cotton, Wool, Flax, and Silk.

MAN has been properly defined a tool-using animal. This faculty was first exercised in agriculture; for we read that Adam was set to his penal task of tilling the ground immediately on his expulsion from Eden. He was then clothed in coats of skins. We have no authentic notice in sacred or profane history when tools were first employed in making cloth; but there can be little doubt that fibres of wool were twisted and woven, under the tuition of their benignant Creator, by the family of Jabal, the antediluvian shepherd, as we find raiment familiarly spoken of immediately after the flood. This valuable art was transmitted by the posterity of Noah to the oriental nations, and was soon carried to high perfection in Egypt and India, but seems to have been lost by many of the migrating tribes in their pilgrimages to the north and the west.

The early inhabitants of Greece were dressed in skins. Their posterity had an obscure tradition that their forefathers had been taught the art of spinning by a divine instructress, which, with their usual fancy, they afterwards embodied in a mythological legend. In these primeval times, indeed, so few generations had intervened since the days of Noah, “ the just man and perfect who walked with God,” that the sentiment of heavenly communion prevailed among most nations, and was particularly cherished by the sensitive and intellectual inhabitants of Greece. It was Ceres who showed them how to cultivate grain, Bacchus to plant a vineyard, and Pomona to graft fruit trees; each instruction being deemed divine. Minerva was worshipped for the sake of sundry benefactions. In the fruit of the olive tree, she furnished bland oil to season their corn or fish as well as to trim the student’s lamp; and in the distaff and the loom she taught the art of converting loose flocks of wool into elegant and durable garments.

These implements were the favourite attributes of the tutelary power of Athens, and constituted in the eyes of its ingenious citizens her chief claim to a seat on Olympus. According to Homer, spinning and weaving appear to have been held in the highest reverence in the heroic ages; they were not vulgarized by common hands, but were the proud prerogatives of queens and princesses. Nor need we wonder at the honours paid to the loom by a people ill supplied with the conveniences of life, however heroic their conduct and sentiments might be; for if an English maiden were now set down among the simple-minded inhabitants of some lonely Australian isle with a spinning wheel and knitting frame, she would doubtless be hailed as a celestial visitant.

We above all others ought to respect the artisans of such invaluable industry, however lowly their modern place in artificial society. To mock the humble toil and obscure destiny which pre-eminently contribute to the grandeur of Great Britain would be a despicable pride. The few among our ancestors who in the time of Julius Caesar aspired to the luxury of dress, wrapped themselves in the hides of beasts killed in the chase; and it was only after being subdued by him and his successors, that they learned the mystery of working wool into a robe to cover their calico skins. The Romans, by imparting such valuable instruction to the shivering tenants of the forest and morass, came to be regarded by our forefathers as benignant patrons, whose departure in the decline of the empire was deprecated and deplored by them in the most affectionate manner.

The textile fibres, cotton, wool, silk, flax, and hemp, differ considerably from each other in structure; the first three consist of definite and entire filaments not divisible without decomposition; the last two consist of fibrils bundled together in parallel directions, which are easily separable into much more minute filaments. These bundles are bound by parenchymatous rings, from which they are freed in the operations of heckling, spinning, and bleaching. Weak alkaline leys dissolve these rings without acting on the linen fibres.

The downy filaments of cotton are cylindrical tubes in the growing state, but get more or less flattened in the maturation and drying of the wool. They are shut at both ends. Their flattened diameter varies from 1/500 to 1/3000 of an inch, according to their quality, as will be fully described in the treatise on the cotton manufacture.

In October, 1833, 1 paid a visit to Paris chiefly with the view of investigating the botanical relations of the different cottons of commerce, and learning what progress was making in the application of the microscope to organic chemistry. I had the good fortune to procure at that time an achromatic microscope of extraordinary power and distinctness, made by Georges Ober-haiiser, a German optician resident in that city, and I directed it immediately to the examination of cotton and flax fibres. In December or January following, I made known the results of my observations to several of my scientific friends at the Royal Society, and being requested by Mr, Pettigrew to submit mummy cloth to my microscope, I accordingly did so, and communicated to him the following statement, which was published in March, 1834, in a foot note to page 91 of his interesting History of Egyptian Mummies :

“ Dr. Ure has been so good as to make known to me that which I conceive to be the most satisfactory test of the absolute nature of flax and cotton, and in the course of his microscopic researches on the structure of textile fibres, he has succeeded in determining their distinctive characters. From a most precise and accurate examination of these substances, he has been able to draw the following statement:—

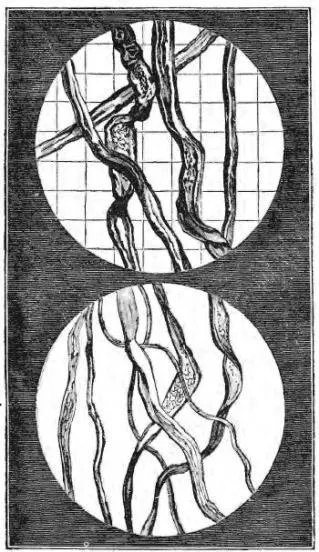

“ ‘ The filaments of flax have a glassy lustre when viewed by daylight in a good microscope, and a cylindrical form, which is very rarely flattened. Their diameter is about the two-thousandth part of an inch; they break transversely with a smooth surface like a tube of glass cut with a file. A line of light distinguishes their axis, with a deep shading on one side only, or on both sides according to the direction in which the incident rays fall on the filaments.

“ ‘ The filaments of cotton are almost never true cylinders, but are more or less flattened or tortuous; so that when viewed under the microscope they appear in one part like a riband from the one thousandth to the twelve-hundredth part of an inch broad, and in another like a sharp edge or narrow line. They have a pearly translucency in the middle space, with a dark narrow border at each side like a hem. When broken across, the fracture is fibrous or pointed. Mummy cloth, tried by these criteria in the microscope, appears to be composed, both in its warp and woof yarns, of flax and not of cotton. A great variety of the swathing fillets have been examined with an excellent achromatic microscope, and they have all evinced the absence of cotton filaments,’ ”

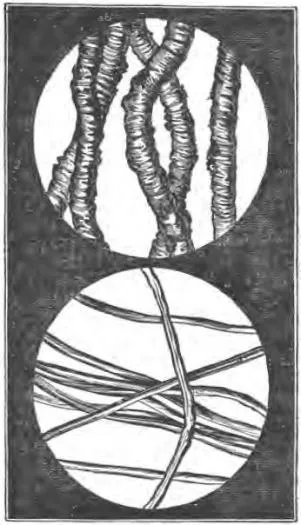

A few months after the date of this publication, on showing my very excellent friend, James Thomson, Esq. of Clitheroe, P.R.S., then in London, the appearance of cotton fibres in my microscope, he informed me that the subject of mummy cloth, with which I had been lately occupied, had several years before engaged his attention. He has since published an ingenious paper on the subject with sketches of cotton and flax fibres, taken from the microscope by Mr. Bauer, who represents flax as uniformly marked at regular distances in each filament with channelled articulations at right angles to its axis; and cotton as consisting of two cylindrical cords, connected by a thin membrane, which are twisted spirally about each other. It appears to me that the cotton has been viewed by him when impasted in Canada balsam or some similar varnish, whereby its fibres have derived certain peculiarities of appearance, which are not visible when they are viewed in less powerful refracting media.

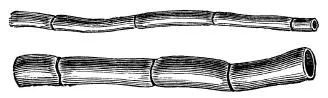

Fig.4. Flax, as represented by Mr. Bauer,

Fig.5. Cotton, as represented by Mr. Bauer.

The figures of flax as seen in my microscope with a magnifying power of 300 are exceedingly distinct, and yet they never exhibit rectangularly placed, cane-like furrowed joints; they show occasionally, indeed, cross lines, at variable angles to the axis, but at irregular intervals, though frequently they show no cross lines at all, even when the filaments are impasted in balsam.

Fig.6. Sea Island Cotton, as viewed by me, in balsam.

When fibres of cotton are viewed in the balsam, they appear very different in the microscope, from what they do when viewed alone or immersed in a film of water, in consequence of the small difference between their refractive power and that of the medium. All the beautiful veining of the riband surface in these circumstances disappears, and of course none of it is represented by Mr. Bauer. The thin shrivelled edges of the ribands also look as if they were enlarged into cylindrical cords. In fact the distinctive marks of the different commercial samples of cotton—the Sea Island, the Upland, the New Orleans, the Surat, &c., which constitute the valuable objects of this kind of research, are in that way entirely lost and confounded.

Fig. 7.— Smyrna Cotton, shown on the micrometer lines, in glass, 1/1000 of an inch apprt.—One million of these squares are contained in one square inch.

Fig. 8.—Surat Cotton—both are irregular riband-form.

When viewed in their dry state or moistened with water, the Sea Island and the Smyrna cottons are seen to be remarkably dissimilar (compare fig. 7 and fig. 8); but when viewed, as Mr. Bauer seems to have done, in balsam, they are hardly distinguishable. Unless great attention be bestowed on the refractive influence of the media in which objects are placed for examination, the microscope is sure to become the source of numberless illusions and false judgments, as M. Raspail has abundantly shown in his Chimie Organique. I have found liquid albumen (white of egg) a good medium for many objects, as it serves to show the outlines distinctly without distorting them.* —See note A.

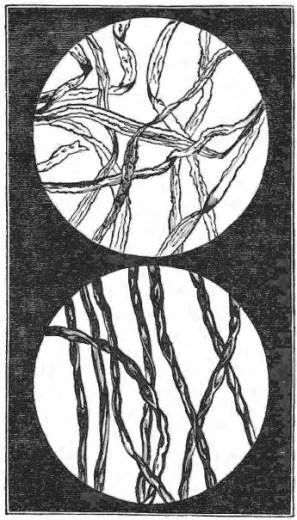

Fig. 9.—Religious Cotton, of which threads are worn by the Brahmins.—It has a very flimsy fibre.

Fig. 10.—Best Sea Island Cotton, of which lace and fine muslin are mode.—Fibre, 1/5000 of an inchtortuous semi-cylinders of uniform size.

Some modern inquirers pique themselves on their power of vision with a single lens microscope; but they will hardly pretend to decypher by its means the minute cross lines of flax or of wool. If such an instrument, when used with no common perspicacity and patience, led Lewenhoeck to describe the filaments of cotton as being all triangular, with fine sharp edges, and therefore very irritating when applied to ulcers, to what errors may it not give birth, with common hands and eyes ! When I find a microscopic observer so justly celebrated as Mr. Bauer, representing both the fibres of flax and cotton under forms which I cannot help regarding as erroneous, I must own that my faith in minute philosophy is impaired. I offer this remark with the less hesitation, as I have verified the results derived from my own instrument with regard to cotton, by a comparison with those obtained from an excellent achromatic microscope by Tully belonging to Mr. Bauerbank, as well as by a very fine one constructed by Mr. Powell of Somers Town. I entertain no doubt that PlcessPs microscope is of the most perfect kind, though it is probably not superior to Powell’s, nor of Mr. Bauer’s general skill in observation ; but I conceive the nature of the medium in which his objects were placed for inspection, has affected their forms very considerably, by refracting or diffracting the light by which they were viewed.

Wool and silk, however, may be viewed with most advantage impasted in Canada balsam slightly thinned with oil of turpentine, for water does not assimilate well with their fibres, nor with their refracting power.

Fig. 11.—Australian Merino Wool.—Mr. Me.Arthur’s breed.

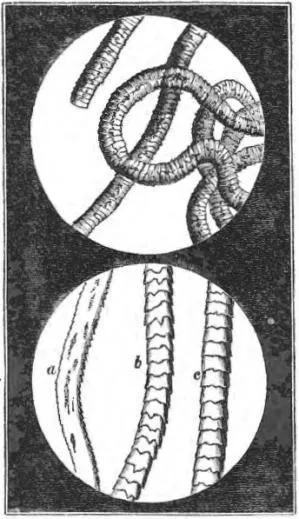

Fig. 12,—a, Leicestershire Wool; b, finest Saxony; c ditto Spanish.

The filaments of wool so seen in a powerful achromatic microscope have somewhat of the appearance of a snake, with the edges of its scales turned out a little from the surface, so as to make the profile line of the sides look like a fine saw, with the teeth sloping in the direction from the roots to the points. Each fibre of wool seems to consist of serrated rings imbricated over each other, like the joints of equisetum. The teeth differ in size and prominence in different wools, as well as the annular spaces between them—the latter being in general from 1/2000 to 1/3000 of an inch, while the diameter of the filament itself may vary from 1/1000 to 1/1400. The transverse lines resemble a little the wrinkles of an earth worm, but they are less regular in their course, Were a number of thimbles with uneven edges to be inserted in each other, a cylinder would result not dissimilar in outline from a filament of Spanish merino wool,—the fleece in which this texture is best developed. In the finest Saxony wool, the articulated appearance is also prominent, and of course the serrated profile of the edges. They are, likewise, well marked in Mr. McArthur’s best long combing wool. In the Leicestershire long staple, the serrations are very minute, and the cross markings indistinct.

When the filament of wool is viewed in its dry state in a good microscope, it shows sometimes warty excrescences, but not (see fig. 13) the articulated texture, on account of the refraction and diffraction of light; though, when it is immersed in a thin stratum of turpentine, varnish, or oil, it exhibits these serrations most distinctly; but the warts vanish in the medium. This examination cannot be well made with even a good compound microscope of the ordinary construction; it requires for its satisfactory completion an achromatic instrument with a linear magnifying power of nearly 300. The felting property depends on the serrated mechanism, but is not proportional to its development. The imbrications of the fibres lay hold on each other, as clicks do on ratchet teeth, so that when the wool is alternately compressed and relaxed in mass, they cause an intricate loco-motion among the filaments, urging them onwards till they become compacted into a solid tissue, called felt. In some specimens, the markings cross each other obliquely, with an appearance somewhat like the imbricated scales of pine-tops.

Fig. 13—Wool, as seen alone.

Fig-14.—Flax, as seen alone.

The cocoon-silk threads are twin tubes laid parallel in the act of spinning by the worm, and glued with more or less uniformity together by the varnish which covers their whole surface. Each filament of this thread varies in diameter from 1/1800 to 1/2500 of an inch, the average breadth of the pair being 1/1000, but it is variable in different silks. The Fossombrone, worth from 22s. to 24 s. per pound, consists of four cocoon threads, or of eight ultimate filaments, each of which is about 1/2000 of an inch, and the compound cord is equal to about 1/500. The white Italian Bergam has its ultimate filaments so fine as of an inch. Different raw silks or singles appear in the microscope to vary considerably in the closeness and parallelism of the threads, a circumstance dependent partly on the quality...