- 322 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Population Geography: Progress & Prospect (Routledge Revivals)

About this book

First published in 1986, this book presents a comprehensive overview of the contemporary state of knowledge in the field of population geography. It discusses the contemporary state of the art and surveys new research developments and new thinking in the major branches of the subject. It thereby provides an introductory guide to contemporary trends and forms a reference point for future development in the subject.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter One

Theory and Methodology in Population Geography

Population geography has no one theory, methodology or, for that matter, definition. It is a widely recognised sub-field of geography as a teaching subject and work on population matters is prominent in the research discipline that is geography. But the distinctions between geographies of population, where population is merely one aspect of a complete human geography; spatial perspectives in population studies or demography, and population geography as a separate entity in its own right are exceptionally blurred. Some of these difficulties relate to the inherent problems faced in defining geography, but others stem from the nature of population studies as a diffuse multi-disciplinary specialism.

In order to clarify what are the important elements in this chaotic state of affairs we must begin by examining the origins of competing definitions of population geography. This will provide an introduction to what will be the main concern of this chapter: a discussion of the theoretical and methodological developments in both the geographer’s approach to population and, since it may be that population geography is also being done by non-geographers, population studies in general.

Definitions

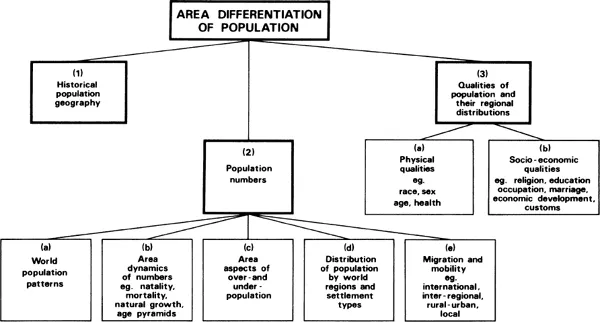

Glenn T Trewartha’s presidential address to the Association of American Geographers in 1953 provides a convenient starting point for our consideration of the various definitions of population geography. Trewartha (1953, see also Kosinski, 1984) was concerned with the need for geographers to treat population matters as a principal sub-discipline (with cultural and physical geography) of a teaching and research subject that was essentially holistic in form. But apart from bemoaning the neglect of population he proposed ‘a system for population geography’ which even thirty years on, is still well worth considering. ‘The geographer’s goal in any or all analyses of population is an understanding of the regional differences in the earth’s covering of people. Just as area of differentiation is the theme of geography in general, so it is of population geography in particular’ (Trewartha, 1953, 87). Population geography is the ‘area analysis of population’, and so Trewartha’s ‘system’ lists ‘the kinds of population features to be observed and compared in different areas’. A diagramatic summary of Trewartha’s (1953, 88–87) ‘system’ is illustrated in Figure 1.1. The objective, shown in the top-centre box, is to understand the area differentiation of population, but this is accomplished via at least three routes: historical, numerical and qualitative. The second box in Figure 1.1 seems the most important since it covers mortality and fertility variations (2b): the distribution of population, settlement size and urbanisation (2d): migration at various scales (2e): but is also linked with notions of resources and carrying capacities (2c). The third box relates to area differentiation in the qualities of population; some of which are physical (3a) and some socio-economic (3b). The point needs to be emphasised that Trewartha’s ‘system’ would regard area differentiation in, for example, levels of economic development as part of population geography. This is entirely consistent since the other two thirds of the geography triangle are physical and cultural, neither of which would presumably deal with economic development as a central issue.

Fig. 1.1 A diagramatic summary of G.T. Trewartha’s ‘system for population geography’.

(Source: based on Trewartha, 1953, 88–89)

(Source: based on Trewartha, 1953, 88–89)

Although Trewartha argued the case for population as the ‘pivotal element in geography’ he was also aware that, ‘there is bound to be lack of agreement on the full content of the field of population geography and admittedly there is no one way or best way of ordering and arranging the topics to be included. Still, in most disciplines and branches of disciplines, there is a core of content on which there is reasonable agreement, even though the full content and its arrangement may bear the stamp of individual authorship’ (Trewartha, 1953, 87). Despite changes in geography as a teaching subject and research discipline many authors have used Trewartha’s ‘system’ over the last thirty years. John I. Clarke’s (Clarke, 1965 and 1972), approach has been particularly influential. ‘Population geography… is concerned with demonstrating how spatial variations in the distribution, composition, migrations and growth of populations are related to spatial variations in the nature of places’, and thus ‘population geographers endeavour to unravel the complex inter-relationships between physical and human environments on the one hand, and population on the other. The explanation and analysis of these inter-relationships is the real substance of population geography’ (Clarke 1972, 2; see also Clarke, 1984). More recently, Robin J. Pryor (1984) begins his review of methodological problems in population geography with: ‘It is assumed here that population geography deals with the analysis and explanation of interrelationships between population phenomena and the geographic character of places as both vary through time and space. Population phenomena include the dynamics of population distribution, urban/rural location, density and growth (or decline); mortality, fertility, and migration; and structural characteristics including age, sex, ethnicity, marital status, economic composition, nationality, and religion’ (Pryor, 1984, 25). Here we have a workable and unified definition that links Trewartha’s ‘system’ with Clarke’s concern with spatial variations in populations and places.

This broad definition is also reflected in Daniel Noin’s Geographie de la Population (1979) and Jurgen Bohr’s Bevölkerungsgeographie (1983). Both authors are concerned with the spatial distribution of population, with the components of its growth and with the characteristics of populations. Noin’s (1984) survey of the contents of population geography textbooks published during the last twenty years shows quite clearly that the broad definition has been the one most widely adopted and that its chief distinguishing characteristic is a close adherence to Trewartha’s ‘system’ but especially boxes 2d, 3a and 3b. Other definitions and approaches have been proposed, however.

The narrow definition is to be found in Hoods (1979, 1982) and Jones (1981). Their approach, both stated and implied, is largely concerned with material related to boxes 2b and 2e in Figure 1.1. That is variations in population dynamics approached via an analysis of the mortality, fertility and migration components at various scales, in the case of Jones (1981), and more generally the study of population from the spatial perspective. The narrow definition deliberately neglects population distribution and redistribution (2d) and the ‘qualities of populations’ (3), except in the sense that the latter affects the components. This attempt to narrow the field of view and to develop a demographic geography or spatial demography has not gone unchallenged by the advocates of the broad definition (see, for example, Clarke, 1980, 1984) who, as we have seen, still adhere to Trewartha’s ‘system’ of Figure 1.1. They would answer Clarke’s (1980, 368) question, ‘How much more demographic should population geography become?’ in a way that would accept the techniques of analysis developed by demographers, but would reject the wider methodology and objectives. Newman and Matzke (1984) seem to suggest a sensible compromise. For them ‘population geography is a relatively open field of inquiry. It does have a recognisable core, but there is considerable room for many issues that relate to people and their well-being’ (Newman and Matzke, 1984, 6). However, the core comprises the demographic variables, population change and distribution; while beyond may lie ‘social and economic indicators’ (e.g. language, ethnicity, religion, occupation); residential characteristics’ (rural and urban); and ‘population in its broader human context’ (e.g. resources, politics, policy).

It might be objected that an extended debate over the definition and content of population geography is bound to be arid at best, destructive at worst, that population geography should be what geographers active in teaching and research on population do. There is no need for either a broad or narrow definition where inter-disciplinary boundaries are being crossed with increasing ease and by growing numbers. All this may be so, but one is left to ponder a riddle set by Clarke (1977, 136), ‘Why has the academic influence of population geographers been less significant than their numbers would suggest?’ ‘Academic influence’ will be taken to stem from the theoretical insights provided by a discipline or sub-discipline together with the empirical knowledge, but perhaps especially the useful knowledge, accumulated and the ability to predict successfully. Using these criteria it may be appreciated why geography as a research discipline lacks academic influence; why within the discipline the influence of population geography and population geographers has been relatively insignificant; and why the same could be said of geography’s influence on demography or population studies. As Jones (1981, vi) has remarked, ‘Population geographers have not figured among the stormtroopers of methodological transformation in geography in recent years…’

My answer to Clarke’s riddle is to argue that because of the broad definition population geographers have spread themselves too thinly over too large a field; that generally they have not mastered the techniques of demography as Trewartha (1953) advised them to; and that they have been unadventurous in their willingness to develop new concepts for understanding and prediction. Of course there have been exceptions and there are signs of change, but most are very recent. I shall consider the theory and method aspects of this argument in the next section, and only two examples of the exceptions must suffice at this stage. Regional population forecasting, once described as having remained peripheral to population geography (Clarke, 1980, 389), has shown itself to have great vitality and practical value (see Hoods and Rees, 1986). Similarly the ability of population geographers to assemble and manipulate large data sets of useful knowledge in ways that are convenient to other researchers, planners and decision makers can only enhance their influence (see, for example, Rhind, 1983).

I shall return to this question of academic influence later, but at this stage it is necessary to repeat that there is no one agreed definition of population geography; that the so-called broad and narrow approaches are not mutually exclusive, rather they represent differences of emphasis, and that the persistence of uncertainty may prove a source of weakness. We must now turn to consider the main theme of this chapter, theoretical and methodological developments, but the issue of definitional diversity will remain in the background.

The Need for Theory

All the advantages of working with a theoretical framework need not be spelt out here, but it may be worth emphasising four particular points which are helpful in population geography. First, the use of theoretical statements, that is statements of prospective association, help to focus research which might otherwise become diffuse, aimless or over-empirical. Second, the use of a broad theoretical framework permits inter-disciplinary comparison to be made more forcibly. Third, the consciously interrogative style of theory construction and destruction aids the definition of priorities and creates a sense of progress when a succession of partial solutions are forthcoming. Fourth, the adoption of a theoretical framework makes explicit the need to tackle issues of purpose, meaning, understanding, explanation and interpretation which might otherwise remain at a subconscious level.

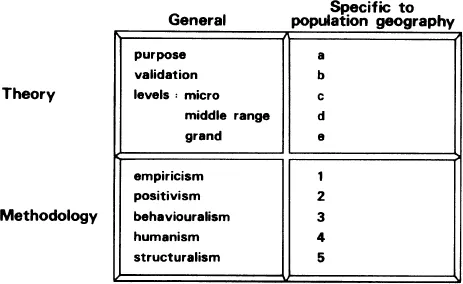

An effect of recognising these points will be to push population geographers closer to the mainstream of methodological debate that has infused human geography in the 1980s. Figure 1.2 indicates some of the issues that will need to be tackled. The upper left pane of the window shows examples of the levels of theory available in general and emphasises both the need to agree upon the purpose of theory construction and the criteria to be used in theory validation (how theories are to be judged). The lower left pane lists five distinctive methodologies which are currently in use amongst geographers, but it does so in a way that suggests a sequential order from empiricism to structuralism which is at least partially in step with recent developments in human geography (Johnston, 1983). The two panes on the right have been left to be completed by the reader, but the rest of this and subsequent chapters will provide discussion of a to e and examples of 1 to 5.

Fig. 1.2 A theoretical window.

Purpose

Consideration of purpose not only returns us to definitional issues introduced above, but it also makes us aware of the differences in levels of understanding that are being sought. For example, there is a clear distinction between studies that seek to model or forecast migration flows using a black box technique and those that attempt an interpretation of human behaviour and decision making with respect to mobility. The former used theory in a modelling sense; they are concerned with the relationships between output and input, with responses to parameter changes and with the need to predict future patterns and distributions. The latter have more intangible objectives. They deal with notions like place utility, satisfaction, environmental stress, stage in the life cycle, bounded and selective rationality and constrained action. These studies seek a broader understanding of why individuals or groups migrate and where they move to, but there are no agreed criteria on what understanding should mean. While some researchers deal with the correlates of flow patterns (Greenwood, 1981) others are concerned with the characteristics of movers compared with stayers (Speare, 1971, White and Hoods, 1980) or the psychology of decision making and implementation (Wolpert, 1964, 1965, 1966; Lieber, 1978; Desbarats, 1983). All contribute to the common stock of information on migration, all use theory to some extent, but even though the ultimate objective can be stated, methods are as diverse as the individual researchers using them.

As far as the use of theory by geographers studying migration is concerned while the general purpose is clear there is little evidence that the diversity of short-term objectives and methods has been explicitly recognised or that the variable status of conclusions has been assessed in ways that reflect such diversity.

Validation

How are theories to be assessed? Can they be proved or merely temporarily accepted while evidence for conclusive rejection is lacking? These are important questions which require careful cons...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Tables

- Dedication

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1. Theory and Methodology in Population Geography

- 2. The British and United States’ Censuses of Population

- 3. Fertility Patterns in the Modern World

- 4. Mortality Patterns in the Modern World

- 5. Government Population Policies

- 6. International Migration: A Spatial Theoretical Approach

- 7. Internal Migration in the Third World

- 8. Counterurbanisation

- 9. Migration and Intra-Urban Mobility

- 10. Population Modelling

- Notes on Contributors

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Population Geography: Progress & Prospect (Routledge Revivals) by Michael Pacione in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.