eBook - ePub

Twenty Years in Khama Country and Pioneering Among the Batuana of Lake Ngami

J.D. Hepburn

This is a test

Share book

- 436 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Twenty Years in Khama Country and Pioneering Among the Batuana of Lake Ngami

J.D. Hepburn

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

An eye-witness account of Khama's struggle for power and a testimony to the leadership and sagacity of khama in church and state.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Twenty Years in Khama Country and Pioneering Among the Batuana of Lake Ngami an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Twenty Years in Khama Country and Pioneering Among the Batuana of Lake Ngami by J.D. Hepburn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Chapter I1

Introductory.—Khama Becomes Chief

“For I determined not to know anything among you, save Jesus Christ, and Him crucified.”—i COR. ii. 2 (R.V.).

“ Then Balak … sent and called Balaam. … to curse you: but I would not hearken unto Balaam; therefore he blessed you still: so I delivered you out of his hand.”—JOSH. xxiv. 10,11 (R.V.).

IN 1870 my husband was appointed missionary to the Bamangwato tribe, at first as colleague to the Rev. John Mackenzie, but afterwards, on the removal of the latter to Kuruman, to take charge of the Moffat Institution (a native training college), we were alone in the work until 1885, when the Rev. E. Lloyd was sent to assist us.

In company with Mr. and Mrs. Mackenzie who had been in England on furlough, we arrived at Shoshong in August 1871.

At a little distance from the town we were met by the two young chiefs, Khama and Khamane, Their welcome of Mr. and Mrs. Mackenzie was very hearty. Mr. Mackenzie had been their missionary for several years. His well-known book, “Ten Years North of the Orange River,” gives a full, graphic, and deeply interesting account of his work among the Bamangwato.

For a few weeks we lived with Mr. and Mrs. Mackenzie, until an old, ruined cottage, which had once been inhabited by Mr. and Mrs. Price, could be repaired. The year that followed our arrival was a very hard and trying one for all of us.

Macheng, a usurping heathen chief, was ruling the tribe when we arrived. He had been installed as chief by Sekhome, in order to keep out Khama, his son and lawful heir. Sekhome was now in exile, his own unnatural conduct and suspicious fears the cause.

Macheng had a visitor, Kuruman, a son of Mosélékatse, and brother of Lobengula, who had lately become chief of the Matabele. Kuruman (so named by his father, in honour of Dr. Moffat, who had been highly esteemed by Mosélékatse), incited Macheng, if indeed he needed incitement, to do his best to get rid of his missionaries, and of all white people. He, Kuruman, meant to send all white people out of the Matabele country when he assumed the government there.

“ Why,” he asked, “ was Macheng such a fool as to allow the missionaries to take away the pillow from under his head? If he permitted them to stay up the kloof, between him and the water, they would take possession of it some day.”

Thus he tried to work upon Macheng’s feelings, and the pair were well mated. Macheng agreed to help Kuruman, and sent three regiments with him to Matabele country for that purpose, giving the command to a relative of his own, but a person of inferior rank in the tribe.

On the march the Bamangwato refused to obey orders, and said they knew no leader but Khama, the son of Sekhome. Macheng’s relative returned in disgrace. This greatly incensed Macheng. He determined to get rid of Khama. In fear of the Bamangwato, who had become alienated from him, if indeed they had ever regarded him as truly their chief, he began to work secretly with native charms and medicines; but these proving of no effect, he tried to buy strychnine for the purpose of poisoning the sons of Sekhome.

A worthless white man took Macheng’s ivory, and promised to get the stuff for him from a store where it was kept to poison wolves. A sharp-witted fellow in the store, suspecting things were not right, sold Macheng’s ignorant European accomplice marking ink, and Macheng got, as he thought, the much-prized powerful agent in his possession. Khama and Khamane were invited by Macheng’s wife to drink coffee, but they respectfully declined, and so Macheng could not succeed in any way.

Macheng now openly persecuted the Christians, giving orders for certain regiments to go out to the veldt (country) to herd his cattle every Sunday, while others were ordered to appear at the khotla (chiefs courtyard) to sew and bray skins of wild animals—anything to prevent the young people from going to school or church.

During those days of persecution several of our young men became sincere Christians, and in later times gave great assistance to their missionary. Many of the young people would march up the kloof, pretending to obey orders; but as soon as they were out of sight of the town they would hide among the hills, and return to the mission premises to attend the services.

Macheng was the most repulsive-looking African I have ever seen. He had lived with Mosélékatse in Matabeleland for many years, and had thoroughly imbibed the abominable customs of these people. He was enormously stout, very fond of fine clothes, indulged unduly in eating and drinking, native beer and Cape brandy being his favourite beverages.

I remember one day he was dining at Mr. Mackenzie’s house. Mrs. Mackenzie asked him a question about a servant whom he had promised to procure for her. Macheng paid no attention to the question, but proceeded diligently with his dinner. When he had finished, he looked up at Mrs. Mackenzie and said, “ One warfare is enough at a time; now I will speak about that business.”

Matters at last reached a crisis, and in August 1872 Khama, with the assistance of Sechele —a neighbouring chief—drove Macheng away, and Khama the Good was chief of the Bamangwato.

So secretly and quietly had the coup d’état been arranged, that Macheng had not the least inkling of his precarious position; indeed, so secure was he and unsuspicious, that he had, with his usual effrontery, the evening before ordered a trader to send him a present of a bag of sugar.

There was little sleep in the mission houses that night. When the dawn broke the poor unsuspecting women and girls, with their earthenware pots on their heads, began trooping up the kloof to procure their daily supply of water.

Suddenly a volley was heard in the town, and we saw the women throw down their pots, and run up the hills in all directions. The firing became louder and sharper, and presently Khama, at the head of a body of armed men, marched quickly past our houses to guard the water. He ran up for a minute to inform us of what had taken place.

Macheng and his adherents had made a hasty flight, but it was feared that they would return and try to possess the wells far up in the kloof, and the only water supply for the whole Bamangwato people.

This they attempted to do; and one party climbed to the top of the hill, immediately at the back of our house, and from this position deliberately fired down upon our houses, and upon Khama’s men who were guarding the water.

Towards evening the firing became serious, some of the bullets falling quite close to us. One hit the ground beside our dog, almost grazing his foot. The poor animal was scared, and began to cry pitifully. Several fell round my husband as he was looking after the sawing of some timber. Even inside our house we were not safe, as the thatch was of reeds, and very worn.

We decided at last to go down to Mr. Mackenzie’s house, which was a good brick building with iron roof. I carried my baby, while my husband, with our other little one in his arms, walked close behind me. As the darkness came the firing ceased; but from the front door of Mr. Mackenzie’s house we could see the burning of the large Makalaka town behind the hills.

For the next few days Khama’s people were occupied in driving Macheng and his followers out of Bamangwato territory.

The following Sunday (August 1872) Khama inaugurated his reign by holding a Christian service in his courtyard, and announced that henceforth only such services should be held there. We all hailed the change with real gratitude and delight, but our joy was shortlived. For on the arrival of old Sekhome heathen abominations were again revived.

A few months after Sekhome’s arrival Khama left Shoshong, and went to live at Serue, a place only a day or two’s journey from the town. Nearly all the Bamangwato followed him, a few old people and some subject tribes remaining with Sekhome and Khamane.

This was a peculiarly dreary and hopeless time, but afterwards it proved to be only the dark hour immediately preceding the dawn, for we shall see, by-and-by, how Khama’s absence was overruled by God to bring about wide-spreading blessing.

“Ill that He blesses is our good,

And unblest good is ill,

And all is right that seems most wrong,

If it be His sweet will.”

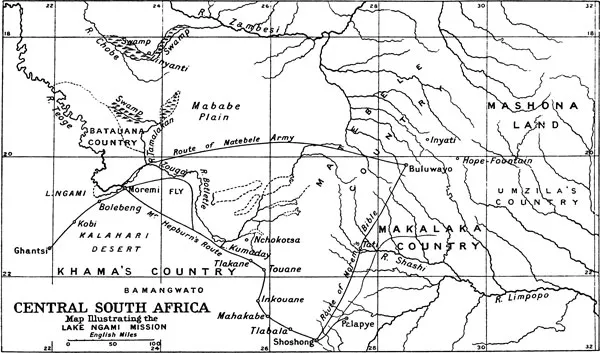

About this time, corn being very scarce, and Mr. Mackenzie not being able to leave his work, my husband decided to go into the Makalaka country to purchase food for the native students and their families.

Twoof these students, KhukweandDiphukwe, accompanied us. They were natives of South Bechuanaland, and earnest, good men. They subsequently offered to go to the Lake Ngami with us when the directors decided to commence that mission.

We were the first missonaries who had visited these Makalaka. They were subject to Lobengula, the chief of the Matabele, and he ruled over them most tyrannically. We have seen the men bury their guns in the veldt to hide them from the Matabele, who periodically would swoop down upon them, robbing and killing, and making slaves of the young people and children.

My husband preached to the Makalaka every Sunday while we were in the country. They understood Sechuana, our language. On our journey back to Shoshong we were overtaken by a party of Matabele, one of Lobengula’s brothers being among them.

Next morning we were informed that this chief had been murdered during the night, and that for this purpose he had been sent out of the country by Lobengula’s orders.

A few months after our return nearly all our Bechuanaland and Matabeleland missionaries came to hold meetings at Shoshong.

Our friends from Matabeleland had no sooner left their homes than Lobengula sent a large war party into Khama’s country, with orders to annihilate a certain village of Bamangwato, a very short distance from Shoshong.

When Messrs. Sykes and Thompson went back all that remained of the village was smoking ruins and corpses. The Matabele soldiers had already returned to their chief with the young people, children, and cattle. All the time we lived in Khama’s country raiding of this kind went on in one direction or another.

The nights at Shoshong during the first few years of our residence there were indescribably painful.

Now and again the mournful wailing for the dead would mingle with the cries of some poor maltreated wife, or slave, who had been unfortunate enough to spoil the husband’s or master’s supper. Again, the weird beat of the drum, accompanying the monotonous chant of the young girls, observing their abominable “ceremony,” would break upon our ear. For weeks at a time these girls would not be allowed to sleep. They were dressed in reeds, and the part of the town where the orgies were carried on was considered sacred. Any one coming near might be stoned with impunity, and intruders could be put to death. On one occasion we were walking past this part of the town, when suddenly we were surprised by a shower of stones.

Then there were the gatherings for beer-drinking, and the consequent quarrels, also the noisy war-dances.

Truly a cleansing was required; but if we had been told that within a few years these horrible noises would give place to hymn singing, and those devilish ceremonies would be supplanted by quiet meetings for the reading and study of God’s word, and praise and prayer, we should have been slow to believe it.

“Come unto Me.” “And Jesus rebuked him, saying, Hold thy peace, and come out of him.” “ I will; be thou made clean.” “ Son, thy sins are forgiven.” “ Whosoever shall do the will of God, the same is My brother and sister and mother.” “ Come forth, thou unclean spirit, out of the man.” “ Daughter, thy faith hath made thee whole; go in peace, and be whole of thy plague.” “ And she went away unto her house, and found the child laid upon the bed, and the devil gone out.”

“ Over the surging multitudes falls the voice of eighteen hundred years ago, quiet, and sweet, and true. That voice will never die. It goes behind, and beneath all time-differences; it enters a region where humanity is one; and the ‘Come unto Me’ which soothed troubled h...