![]()

CHAPTER ONE

Chinese Perspectives of the China Threat: Myth or Reality?

Herbert Yee and Zhu Feng

Introduction

Before 1995, few Chinese leaders or scholars publicly refuted the ‘China Threat Theory’ (Zhongguo weixielun). The People’s Daily (Renmin Ribao), the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) official newspaper, first responded to the China threat issue in October 19921 after the Bush administration decided to sell 150 F-16 fighter jets to Taiwan, and the publication of an article by Ross Munro sounding the China threat alarm.2 The People’s Daily article pointed out that the Bush administration had used the ‘China threat’ as an excuse to sell warplanes to Taiwan. Yet the response of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) to the China threat issue remained sporadic during 1993 and 1994. Until the end of 1994, only five articles in the People’s Daily directly responded to the issue (with titles containing the characters ‘China threat’), while only one scholar addressed the issue.3

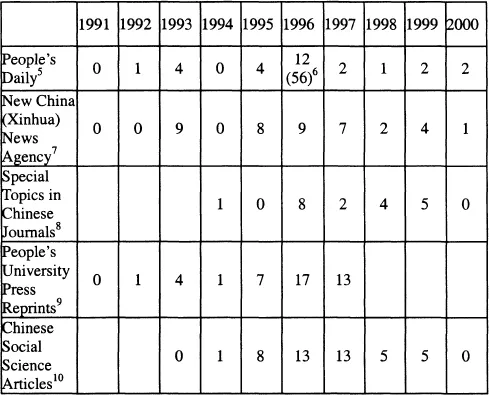

However, the PRC’s responses to the China threat issue rose sharply in 1996, especially after the face-off between the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and US aircraft carriers in the Taiwan Straits. In 1996, twelve People’s Daily articles directly refuted the China threat, while fifty-six news reports and analyses mentioned and criticised the China threat accusations. The quantity of scholarly articles also reached its peak in 1996; eight journal articles directly addressed the China threat issue. However, the Chinese responses gradually declined after 1996 as indicated in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1

Number of Articles and Commentaries on the ‘China Threat’ Appearing in the Chinese Press and Journals (1991–2000)4

This chapter examines Chinese responses to the China threat issue and the arguments with which it has been refuted. Chinese views from three different perspectives will be examined, namely the official, scholarly and societal. We refer to official views as those derived from articles or commentaries appearing in the People’s Daily and other CCP press organs as well as those expressed by Chinese leaders and diplomats in speeches and policy statements. The academic views are mainly derived from articles published in mainland journals by international relations scholars, while the views of the Chinese populace are reflected in opinion polls, popular best sellers, and essays or commentaries on Chinese Internet sites. Admittedly, it is sometimes difficult to clearly distinguish among these three groups, and there is a degree of overlap.

The Official Chinese Response

Chinese leaders or spokesmen for the PRC government normally refute the China threat allegations by stressing China’s independent and peaceful foreign policy, often through elements of the CCP’s propaganda machine such as the state controlled mass media or news agencies. Few Chinese leaders publicly refuted the China threat notion before 1996. However, as mentioned above, when US allegations of a China threat escalated in 1996, responses from the Chinese government also increased sharply. Since 1996 Chinese leaders on official visits abroad or on receiving foreign leaders or journalists in China have often mentioned and refuted the idea that China poses a threat. For instance, in an interview in March 1997, President Jiang Zemin pointed out:

Some circles in the West have deliberately exaggerated China’s economic capability and spread the so-called ‘China threat’ alarm. This allegation is completely groundless. China’s current reform and open policy and its modernisation efforts need a prolonged period of stability and peace in the international environment. Even when China becomes strong and powerful it will not threaten other countries.11

Similarly, Premier Li Peng responded to the China threat in an interview in December 1997:

In order to realise China’s development strategy and its basic objective of raising the level of material well-being and cultural life of the Chinese people, we need, on the one hand, a stable and harmonious domestic political environment and, on the other hand, a peaceful international environment, especially a good environment along China’s borders. These are the prerequisites for China’s continuing development. The Chinese people highly value peace and stability. We oppose great power hegemony and China as a socialist state will never seek hegemony nor a sphere of influence. This is a solemn promise made by the Chinese government to the world. China does not pose a threat to any country or region. Some people spread the ‘China threat’ allegations for other purposes. China’s military capability and posture is defensive — if other people do not attack us, we won’t attack others.12

When Premier Zhu Rongji visited the United States in 1999, he also refuted the China threat as a groundless allegation in a speech delivered in New York. Zhu suggested that it would be better to think of China is an opportunity rather than a threat given the opening of China’s huge domestic market to Western capital and goods, and that China and the United States should be co-operative partners.13

Besides direct rebuttals by Chinese leaders and diplomats, the Chinese government has used its propaganda organs such as the People’s Daily, Liberation Army Daily, and the Xinhua News Agency to refute the China threat. Most articles or commentaries appearing in the official press merely reiterate the PRC’s position – that the allegations are completely groundless, a myth created by the Western anti-Chinese forces, and that: (1) China is a peace-loving country and needs a peaceful international environment for its economic development; (2) China is not a hegemonic power and will never seek hegemony in the region; (3) China’s military capability is defensive and poses no threat to its neighbours; and (4) China will not use nuclear weapons against countries which do not possess nuclear weapons and that it does not have a single soldier or military base overseas. Another common strategy of the official press is to quote the views or opinions of friendly foreign leaders, diplomats, or scholars on the China threat issue.14 By and large, the Chinese official response to the China threat theory is reactive, defensive, and lacks a rigorous and critical theoretical analysis.

However, besides verbal rebuttals the Chinese government has also taken concrete measures to alleviate concerns associated with China’s rising power. First, in 1995, 1998 and 2000 the PRC issued a series of defence white papers explaining China’s good-neighbourly foreign policy tradition, its defensive national defence policy and military modernisation, as well as a plan to reduce the size of the PLA and China’s military expenditure. Secondly, in 1997 the Chinese government set up a ‘Comprehensive National Power Research Group’ consisting of more than a hundred scholars and experts in various fields. The research group used numerous indicators to compare the comprehensive national power (CNP) of the United States, Britain, France, Germany, Russia, Japan and China during the period 1988–1998. The group, which published its report in August 2000, concluded that the PRC, in terms of CNP, should be ranked number seven in the world, and has about a quarter of the United States national strength, less than half of Jaran’s, and about two-thirds of Russia’s (Russia was ranked number six). 15 Thirdly, Chinese officials have deliberately avoided mentioning the term ‘Greater China’ – a vague concept which normally includes mainland China, Taiwan, Hong Kong and Macau, but sometimes is also said to include ethnic Chinese residing in Southeast Asia and elsewhere.

The Views of the Chinese Populace

In contrast to official rebuttals of the China threat, the response from ordinary Chinese citizens to the issue has been largely emotional. Indeed, the issue has aroused a strong wave of nationalist feelings among a significant portion of the Chinese populace, especially among young intellectuals, and helped to change their views of the world, and especially of the United States.

In May 1996, China Can Say No was published and quickly became a bestseller. The book was written by young intellectuals and severely criticised America’s China policy, especially the advocation of a policy of containment by some sections of the US mass media in response to an alleged China threat.16 The authors described their personal experiences in changing from a pro-American to an anti-American stand because of increasingly hostile US policies and attitudes towards the PRC. They also criticised pro-American political forces in China. The popularity of the book and its anti-American overtones immediately drew worldwide attention. It also drew critical reviews from both inside and outside China, which in general regarded the book as too emotional and irrational. Many were quick to point out that the sentiments expressed in the book might not necessarily represent mainstream Chinese feelings towards the United States. Nevertheless, most Western observers were shocked by the authors’ strong anti-American sentiments. Moreover, many believed that the Chinese government had given its tacit support to the book’s publication.17 The Hong Kong-based Asiaweek took a more neutral position, stating: ‘Perhaps, not all Chinese youth are so radical, but as indicated in several opinion surveys conducted in China last year, most Chinese youth regard the American attitude towards China as hegemonic and most unfriendly. It is thus not unreasonable to say that the sentiments as expressed in China Can Say No generally reflect the feelings of the Chinese populace’.18

Following the publication of China Can Say No, several books with similar titles were published later in the same year, namely Why China Says No,19 China Can Still Say No20 and China Can Not Only Say No.21 These books more or less carried the same theme of criticising Washington’s China policy and urging the Chinese government to stand firm against the United States. They served to further fan anti-American sentiments. However, the publication of Behind the Demonisation of China in December 1996 pushed Chinese nationalist feelings to a new height.22 The book targeted its criticisms at the American mass media. It asserted that there exists a strong anti-Chinese current in American academic, publishing, and mass media circles which deliberately distorts China’s image and tries to sell this ‘demonised’ image of China to the American public.

If the China-can-say-no books published in 1996 reflect the vitriolic, chauvinistic, and anti-American feelings of young Chinese intellectuals in the mid 1990s,23 the publication of China’s Future in the Shadow of Globalisation in 1999 signalled a subtle change of attitude among young intellectuals.24 Two of the four co-authors, Qiao Bian and Song Qiang, were co-authors of the first China-can-say-no book. From that book to China’s Future one can discern a change in Qiao and Song’s position from a simple, emotional exclamation of ‘no’ to a more subtle, rational and in-depth analysis of the reasons behind the China threat allegations. The four co-authors try to find a new meaning and role for Chinese nationalism or patriotism in Chinese foreign policy.

An unintended consequence of the China threat allegation is the rising dissatisfaction among the Chinese public towards their country’s foreign policy, especially its US policy. The Chinese government has faced increasing pressure from the public to take a more hard line stance in its dealings with the United States. Over the last few years, a number of articles and commentaries have appeared in academic journals and on the Internet reviewing Chinese foreign policy and suggesting alternative strategies. Some commentaries accuse the Chinese government of being too ‘soft’ in refuting anti-Chinese allegations, and suggest that it should go beyond mere verbal rebuttals. For instance, a commentary by one anonymous writer appeared on the Internet severely criticising the government’s ‘rightist pro-American policy line’, which had, in his opinion, sacrificed Chinese national and strategic interests on the Korean Peninsular, and in the South China Sea and the Taiwan Straits for a stable relationship with the United States.25 After the spy-...