- 336 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This is volume III of six in a series on the Sociology of East Asia. Originally published in 1949, Study of Rural Economy in Yunnan.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Earthbound China by Chih-I Chang,Hsiao Tung-Fei in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Sociología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

LUTS’UN: A COMMUNITY OF PETTY

LANDOWNERS

LUTS’UN is located in a fertile valley, about 100 km. west of Kunming, close to the Burma Road. We started our study with this village because we found here a simple form of economy in which neither commerce nor industry plays an important part. The main occupation of the people is the management and cultivation of farms, and the villagers are either petty landowners or landless laborers. Landlords with large holdings are lacking, and absentee owners are few and insignificant. It seems to us that this village represents a basic type of farming community in interior China. The life of the peasants is characterized by the use of traditional farming techniques on rather fertile land and under a strong pressure of population. In these fundamental ways Luts’un represents, in miniature, traditional China. It is also logically a prototype of the types of villages described later, where the development of handicraft industries and the commercial influence of the town complicate the structure.

Luts’un is a village of 122 households, with 611 individuals—about the average size for the region. The total area of farms owned by the villagers, privately or collectively, is about 920 mow, or about 140 acres.18 Owing to the fertility of the soil, the yield from a unit of farm land is higher even than that of the area around Lake Tai, the well-known rice-producing area in eastern China. However, the distribution of land among the villagers is unequal. Most of them either have no land or have too little land for their maintenance. These must seek employment on the land of others, since there is. little opportunity for gaining a livelihood in occupations other than agriculture, and they form a large supply of hired labor. The petty owners, on the other hand, are able to manage their small estates by employing cheap labor to work for them and themselves to enjoy leisure. The dichotomy of work and leisure among the villagers is characteristic of this type of village economy.

The average size of a holding is small—less than 1 acre. It tends to diminish gradually under the increasing pressure of population, because, according to custom, brothers have equal rights of succession to land. Since there is no open and easy source of income other than in agriculture, most of the small landowners must eventually become landless laborers. Some of them will remain single all their lives and then die out completely. Occasionally rural families may, through hazardous ventures in the outside world, suddenly rise to wealth; but such families are soon leveled down by the merciless pressure of population. One or two generations is quite enough to reduce the holdings of a rich family to petty units. The movement upward on the economic ladder is slow, but the movement downward is rapid. The supply of landless laborers is maintained by a constant increase in the population and a constant decrease in the size of landholdings. The traditional structure of the village is thus dependent upon the existence of two groups of people: the petty owners, who form a leisure class; and the landless laborers. This is the type of rural economy that we shall analyze in the following pages.

CHAPTER I

FARM CALENDAR

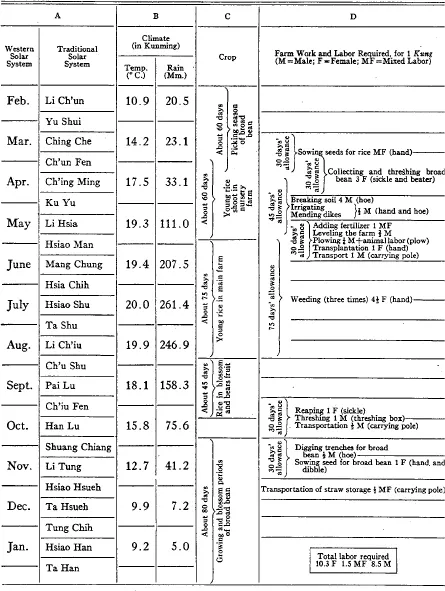

IT WOULD, perhaps, seem desirable to preface a study of the land system by an analysis of the problem of land utilization; but, because of the limitations of our technical knowledge of agriculture, we must confine ourselves to a description of the fundamental data which are necessary as a basis for the later discussions. These data, which constitute the agricultural calendar, are arranged in the form of a table (Table 1) for ready reference. This table will serve the purpose of showing graphically the co-ordination of climate, crop growth, and agricultural activities. The following pages will be devoted to an explanation of the various columns in the calendar.

Three important categories of information appear in the calendar: climatic changes (Column B); the growth process of the crops (Col. C); and the activities, the amount of labor, and the tools required of the farmer in the cultivation of the crops (Col. D). Because these factors are co-ordinated in time by virtue of the nature of agriculture, the calendar appears as a system of vertical and horizontal co-ordinates. The process of growth, determined by the physiology of the plants and by the climate, is not subject to the desires of man. The human effort expended on the farm simply provides the plants with an opportunity to grow. As Mencius said: “It is foolish to pull the shoots to help them grow.” Since different crops differ physiologically and in their response to the climate, an understanding of the agricultural activities of a people requires a knowledge of the kind of crops grown and the climatic conditions to which they are subject. Hence our discussion begins with Column C.

I. CROPS AND CLIMATE

Only two crops—rice and broad beans—are listed, since these serve as the basis of the agricultural economy of the village. From the surrounding higher lands the valley appears to be covered by a solid carpet of green, furnished in early summer by the rice plants and in late fall by the beans. A walk through the fields, however, reveals the presence of additional crops. Corn grows on the sandy land bordering the stream, various vegetables are raised in the gardens back of most of the houses, wheat is planted in scattered squares among the fields of broad beans, and the trailing vines of green beans impede the walker as he traverses the paths between the rice paddies. There are many secondary crops in addition to these, but they are produced in relatively small quantities. Since all of these secondary crops are raised in small quantities and almost exclusively for consumption by the farmers themselves, they do not constitute an important part of the economy and are therefore omitted from the calendar.

TABLE 1

THE CALENDAR OF WORK

Although rice and broad beans are often grown alternately on the same plots of land, the acreage devoted to rice is much greater than that sown with beans. In the absence of actual statistics, our estimate that the bean acreage is approximately 70 per cent of the rice acreage is probably not greatly in error. The explanation for this fact lies in two factors: soil and terrain. Owing to the narrowness of the valley and the rocky deforested nature of the mountains surrounding it, the small tributary streams carry a considerable load of sand. The flooding of these streams results in small areas with sandy soil, which are not suitable for rice cultivation but must be devoted to corn and other crops. The land farther away from the streams is of two types, both of which are suitable for rice. On the higher slopes at the east side of the village, the loose, well-drained soil is excellent for broad beans, though it does not produce abundant crops of rice. Farms in this area are invariably double-cropped. On the lower slopes, nearer the main stream, on the other hand, since the sticky, poorly drained soil is ideal for rice but unsatisfactory for beans, the fields usually lie idle during the autumn and winter.

Column B of the calendar provides data on two significant climatic factors—temperature and rainfall. Before discussing the significance of the climate in the agriculture of the village, a few notes relative to the validity of the data given are in order. The first is in regard to the source of the figures. Since there are no recording instruments in or near the village, it has been necessary to utilize the records taken in Kunming, which is about 100 km. east of Luts’un. If other factors were uniform, this distance would not be important climatically; but there is a difference in altitude which is reflected in the respective climates of the two localities. Luts’un, with an elevation of only about 1,650 meters above sea-level, is more than 200 meters lower than Kunming, at 1,890 meters, and is consequently warmer. The degree to which the climate of the village varies from that in the provincial capital has not been directly measured, but it may be observed indirectly in the agriculture. The variety of rice grown in Luts’un (a type with grains which drop readily from the stalk when ripe, thus requiring a short harvest period) is not raised in the Kunming area. Furthermore, the harvest is earlier at the lower altitude—a fact the importance of which in the labor situation will be discussed later. In 1939, on our return from Luts’un, where the gathering of the rice crop had been completed before October 15, we found the harvest just begun in Kunming. There is, thus, a discrepancy of approximately one month in the agricultural calendars of the two regions.

A second characteristic of the temperature and rainfall figures should be noted—namely, that they represent an average for the years 1929–36 and lack validity for any specific year. That there is actually considerable variation from year to year is demonstrated by the situation in 1939, when the spring was unusually late. According to the custom of previous years, the farmers of the village sowed their rice seed in the nurseries shortly after Ching Che (the middle of March). But seven days after Ch’un Fen, i.e., on March 28, the germinated seeds were killed by frost, and the final sowing was not accomplished until the eleventh day after Ch’ing Ming, twenty days later. In other words, in that year the actual agricultural calendar lagged one month behind the traditional calendar based on the climatic average. Therefore, it is obvious that the figures given have value only for general reference purposes.

Two outstanding characteristics of the climate are revealed by the figures appearing in Column B. The first is the relatively slight annual variation in temperature. The difference between July (the hottest month), with an average temperature of 20° C. (68° F.), and January (the coldest month), with an average of 9.2° C. (48.5° F.), is only 10.8° C. (19.5° F.). The second characteristic is the high variation in precipitation, which amounts to 261.4 millimeters in July but totals only 5 mm. in January. The monsoon season, which begins suddenly in May, extends through September and is followed by the dry season, which terminates at the end of April. These two peculiarities, taken together, constitute a climatic complex to which the agricultural complex here is admirably adapted. The lack of severe cold permits a perpetual growing season, and thus the double-cropping of the land, with only brief intervening periods for the preparation of the soil. Rice and broad bean make the ideal combination for complete utilization of the land, since the former requires warmth and a constant water supply, while the latter needs dry weather and lower temperatures.

II. FARMING ACTIVITIES

Although the growth of the crop, which is a continuous process, governs the farming activities, the latter are discontinuous. Before the crop is planted, there is a period of preparation of the soil; but after the planting, only weeding and irrigation are necessary until harvest time, when the work is again heavy. The concentration of well-defined types of farming activities in definite periods, with intervening seasons of relative idleness, justifies the use of the concept of sections of work. In Column D are listed the various sections of work, together with the amount of labor required for each.

The ideal method of collecting the data for this column would be direct observation by the investigator for a full year, with a complete day-by-day record of the actual work of the observed individuals. Since we were unable to remain in the village for a year, this method was impossible, and we had to resort to the use of informants, checking the information so obtained against the direct observations we were able to make during our investigations. The key to the problem of securing accurate information by this method is, of course, the selection of the proper informants, which we did not find difficult after a period of residence with the villagers. Dishonest and evasive answers are relatively easily detected by posing the same questions to several individuals and by asking related questions of a single person. Perhaps the most essential requirement for the investigator is a constant awareness that the information and experience of the individuals in a community are not uniform. It is impossible to acquire complete and satisfactory knowledge of the conditions in the school by questioning a shopkeeper. Although it would seem that this requisite for sound field work is so self-evident that it need not even be mentioned, there have been instances in which investigators have reached absurd conclusions as a result of averaging equally weighted answers from indiscriminately selected informants. Hence, it is vital that the necessity for selecting the proper informants for the specific inquiry be steadfastly borne in mind.

The securing of good informants presents no difficulty as far as some of the items in the agricultural calendar are concerned; examples of these are the process of crop growth and the sequence of farming activities. Anyone connected with agriculture, whether he be an actual worker on the farm or one who employs others to manage his land, can give, without hesitation, the number of days which elapse between the germination of the grain and the harvest or the succession of tasks involved in cultivation. As a matter of fact, similar information can be obtained from almost anyone in the village. A fourteen-year-old boy living near my house once recited to me the complete annual agricultural cycle without omission or deviation from the proper order.

My original assumption that such problems as the dates of the beginning and the completion of each section of work would be readily solved by the simple expedient of asking anyone engaged in agriculture was quickly demolished by the variety of answers to my questions given by different individuals. Some responded with the actual dates for the current year; others, with dates from the standardized calendar. Every year each household sets its own dates for each type of work. In 1939, for example, some households sowed their rice seed as early as the eighth day of the second moon, while the rest selected dates as much as ten days later. The standard calendar prescribes, not the dates for each activity, but the period within whose limits the activity must be accomplished. It sets the date before which the work in question should not be done and the date by which it should be completed. A villager expressed this in describing to us the schedule for rice cultivation: “After Ching Che the seeds may be germinated. After remaining in the nursery farms for sixty days, the rice should be transplanted to the main fields, but this should not be done later than Hsia Chih. The weeding may start not earlier than fifteen days after transplantation and should not continue beyond Li Ch’iu.” It is apparent that the standard calendar consists of a set of terminal dates within which the individual calendars may vary. It is a system of reference based on the accumulated experience of the people and may, like other rules derived from experience, fail to meet a specific situation. As mentioned in the preceding section, the villagers attempted to adjust their activities to the standard calendar in 1939, with the result that the seed they sowed was wasted. Contrary to the general rule that all sowing must be completed before Ch’ing Ming, only the seed sown after that date in 1939 was successfully germinated. The villagers considered this an exceptional circumstance and said that “something was wrong with the heavens.” Despite the 1939 failure, it is clear that, given the lack of better means for predicting temperatures and the need for a system of reference to make advance planning possible, the preponderance of past experience must be accepted as a guide.

While the standard calendar can be repeated in its entirety by everyone, this is not true of the individual calendars of work. These are different for different households, who usually do not remember even their own. The only effective method for collecting them would be the maintenance of a diary for each household, a difficult task under the conditions of our investigation. In 1939 we attempted, by direct observation, to enumerate the hired laborers in the fields; but, after a full day of work, we found that we had missed a number of them. In view of the impracticability of maintaining detailed daily records of the activities of several households, we did not attempt to collect individual calendars but are, instead, presenting the standard calendar as an adequate exposition of the agricultural cycle.

III. TIME RECKONING

In Column A appear the divisions of the Western and of the traditional Chinese solar calendars. It will be noted that the climate column is co-ordinated with the Western system, while the other two columns are subdivided vertically to correspond with the Chinese calendar. This is necessary because of the different sources of data for the various columns. The climatic record is taken from the Chinese Yearbook, where it is organized according to the Western system. Although we are aware of no precedent for this in the literature on Chinese economic problems, we are using the traditional system as our primary frame of reference because it is the system by which the farmers themselves regulate their farming activities. It seems to us that, for the best understanding of the life of a people, their activities should be studied, as far as possible, in terms of their own systems of reference. The local system may then be correlated with the system familiar to the reader. Time reckoning is a basic part of the life of a community; and, being man-made, it is adapted to the needs of that community. It is a functioning element in the culture and cannot be understood without reference to the experiences of the people. Since time itself is continuous, its division into units is a cultural phenomenon, which means that it is designed to serve human purposes. This is why we believe that the imposition of the time system of one group upon the study of another is a real obstacle to an investigation.

The Chinese peasants use two calendrical systems—a lunar and a solar—both of which have been described in a previous book.19 We need restate here only a few salient features of these systems in order to indicate the reasons for the fact that the solar calendar prevails as the system of reference in agriculture. Since the lunar cycle is 29.53 days, the months are either 29 or 30 days long. The discrepancy between the lunar calendar and the solar calendar resulting from the fact that twelve lunar months amount to only about 354 days, necessitates the insertion of an intercalary month every few years. But even with this correction, the differences between the two calendars may amount to more than 10 days. Since agricultural activities must be adjusted to the growth processes of the crops, and ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Contents

- FOREWORD

- INTRODUCTION

- PART I. LUTS’UN: A COMMUNITY OF PETTY LANDOWNERS

- I. FARM CALENDAR

- II. AGRICULTURAL EMPLOYMENT

- III. SOURCES OF FAMILY INCOMES

- IV. DISTRIBUTION OF LANDOWNERSHIP

- V. FARM LABORERS

- VI. FARM MANAGEMENT BY PETTY OWNERS

- VII. TENANCY

- VIII. FAMILY BUDGETS

- IX. INHERITANCE OF LAND

- X. FAMILY FINANCE

- XI. LAND TRANSACTIONS

- PART II. YITS’UN: RURAL INDUSTRY AND THE LAND

- XII. LAND UTILIZATION

- XIII. FARM LABOR

- XIV. INVESTMENTS IN AGRICULTURE

- XV. STANDARDS OF LIVING

- XVI. SOURCES OF INCOME OTHER THAN INDUSTRY AND AGRICULTURE

- XVII. BASKETRY

- XVIII. NATURE AND ORGANIZATION OF THE PAPER INDUSTRY

- XIX. PAPERMAKING AND MARKETING OF PAPER

- XX. MANAGEMENT AND PROFIT IN THE PAPER INDUSTRY

- XXI. CAPITAL AND LAND

- PART III. YUTS’UN: COMMERCE AND THE LAND

- XXII. FARMING AND TRUCK GARDENING

- XXIII. LAND TENURE

- XXIV. SUPPLEMENTARY OCCUPATIONS

- XXV. HOUSEHOLD CONSUMPTION

- XXVI. POPULATION MOVEMENTS

- XXVII. THE ACQUISITION OF WEALTH

- XXVIII. THE EFFECTS OF COMMERCE ON VILLAGE HOUSEHOLDS

- CONCLUSION

- AGRICULTURE AND INDUSTRY

- INDEX

- PLATES