- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Dance In Society Ils 85

About this book

This is Volume II of nine in a collection on the Sociology of Culture. Originally published in 1969 this is an analysis of the relationship between the social dance and society in England from the Middle Ages to the 1960s.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Dance In Society Ils 85 by Frances Rust in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

BACKGROUND

II

Anthropological Perspectives

(a) Nature and Origin of Dancing

An analysis of the nature and origin of dancing involves a consideration of three questions: What is dancing? When did man first begin to dance, and Why? The questions are clear-cut, but the answers can only be described as hazy.

Voss, for example, devotes twelve pages to cited definitions of dancing,9 and equal confusion reigns over questions of origin and motivation. The following definition of dancing given by A. E. Crawley,10 however, has the merit of being both simple and non-controversial, and in addition gives a meaningful answer to the question – What is dancing? ‘Dancing, in its proper sense, consists in rhythmical movement of any part or all parts of the body in accordance with some scheme of individual or concerted action.’ No one knows for certain when man first began to dance (in this sense), or why. It is not improbable that dancing preceded speech – a theory developed by Langer, who traces the origin of dance to the spontaneous, self-expressive movements and gestures of man which functioned as symbols of communication long before language.11

Other theories go even further back in the history of mankind, tracing dance and its basic circle form to man’s animal ancestors, particularly the lively, playful circle dances of the apes. Of immense interest here is Köhler’s detailed description of a genuine round dance of the anthropoid apes in Teneriffe:

. . . two of them . . . begin to circle about, using the post as a pivot. One after another the rest of the animals appear, join the circle, and finally the whole group, one behind the other, is marching in orderly fashion around the post. Now their movements change quickly. They are no longer walking but trotting. Stamping with one foot and putting the other down lightly, they beat out what approaches a distinct rhythm, with each of them tending to keep step with the rest. Sometimes they bring their heads into play and bob them up and down, with jaws loose, in time with the stamping of their feet. All the animals appear to take a keen delight in this primitive round dance . . . Once I saw an animal, snapping comically at the one behind, walk backwards in the circle. Not infrequently one of them would whirl as he marched about with the rest. When two posts stand close to each other, they like to use these as a centre, and in this case the ring dance around both takes the shape of an ellipse. In these dances the chimpanzee likes to bedeck his body with all sorts of things, especially strings, vines and rags that dangle and swing in the air as he moves about . . .12

Curt Sachs points out13 that this description shows a series of completely recognizable motifs: the circle and ellipse as forms: the forward and backward pace: hopping, rhythmical stamping and whirling as movements: and even a form of ornamentation for the dance.

Following this line of thinking, the question of when man first began to dance loses some of its meaning, since the origin of dance appears to be traceable back to the very origin of mankind.

The question why posed at the beginning of the chapter can similarly be answered only in theoretical terms.

Many theorists14 take the view that dancing is an instinctive mode of muscular reaction – whose function is either to express feeling or emotion or, at other times, simply to express ‘excess energy’. In the latter case, dancing is seen as an aspect or development of physical ‘play’. These views are supported by well-observed studies not only of animals (as, for example, the apes observed by Köhler), but also of birds and insects. ‘Courtship’ dances, where the male dances to attract and rouse the female, are common in the bird and insect kingdoms, and at other times there seem to be clear instances of dances which are simply an expression of play, individual or group. The dance of the argus pheasant, the ‘waltz’ of the ostrich, and the bowing and scraping of the penguin are well-known, but perhaps no account is more vivid than that of MacLaren15 describing the dance of the stilt birds in Cape York, North East Australia:

There were some hundreds of them [the birds] and their dance was in the manner of quadrille, but in the matter of rhythm and grace excelling any quadrille that ever was. In groups of a score or more they advanced and retreated, lifting high their long legs and standing on their toes, now and then bowing gracefully one to another, now and then one pair encircling with prancing daintiness a group whose heads moved upwards, downwards and sideways in time to the stepping of the pair. At times they formed into one great, prancing mass . . . then suddenly . . . they would sway apart, some of them to rise in low, encircling flight . . .; and presently they would form in pairs or sets of pairs, and the prancing and the bowing, and advancing and retreating would begin all over again . . .

It can of course be argued that the ‘leap’ from the animal world to man is too great, even in terms of activities which are claimed to be biological. If animal studies are to be ruled out, however, one can go to the field of child development for equally convincing support for the ‘instinctive’ theory of dancing. Most observers report that at about the age of one and a half the majority of children, without training, start some clearly recognizable rhythmical movement such as bouncing or jumping up and down in response to rhythmic music.16 Abandoning the word ‘instinctive’ as a relatively unhelpful concept when applied to human beings, one can at any rate claim that the bulk of the available evidence indicates that dancing is basically an unlearned, innate, motor/rhythmic muscular reaction to stimuli, whose function for the individual is either to express feeling or to ‘work off’ energy.

This view of the dance is well supported by anthropological accounts of the place it holds in primitive societies. To quote Wundt:

Not the epic song, but the dance . . . constitutes everywhere the most primitive . . . art . . . Whether as a ritual dance, or as a pure emotional expression of the joy in rhythmic bodily movement, it rules the life of primitive men to such a degree that all other forms of art are subordinate to it.17

(b) Primitive Dance

At this stage it is possible to leave theorizing behind and build on solid facts. In the life of primitive peoples, nothing approaches the dance in significance. It is no mere pastime, but a very serious activity. It is not a sin but a sacred act. It is not mere ‘art’ or ‘display’ divorced from the other institutions of society: on the contrary, it is the very basis of survival of the social system in that it contributes significantly to the fulfilment of all of society’s needs. ‘Birth, circumcision, and the consecration of maidens, marriage and death, planting and harvest, the celebrations of chieftains, hunting, war and feasts, the changes of the moon, and sickness – for all of these the dance is needed.’18

The anthropological data on the subject of the dance in primitive society is, indeed, so extensive that only the most significant facts and illustrations can be presented here, bearing in mind, all the while, that much of this should be put into the ‘passing’ tense (to use Gorer’s phrase) since many primitive societies are now being absorbed by the modern world. The first important fact that strikes the sociologist is that the dance is apparently a universal theme in all primitive cultures, wherever one looks – from the jungles of Central Africa to the Amazon swamps – from the coral islands of the Pacific to the snowy wastes of Siberia.

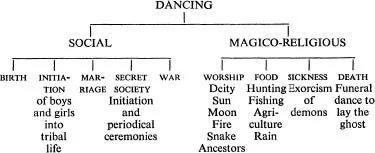

Secondly, from the sociological point of view, the social functions of the dance in primitive cultures can be seen to fall under the following headings,19 all of which can be subsumed under the four main classes of ‘functional problems’ already listed in Chapter I:

Some examples, drawn almost at random from the wealth of available material, may serve to illustrate each of these.

BIRTH

The Kayans of Sarawak, especially those of the Upper Rejang, perform a dance, the purpose of which is to facilitate delivery. The dancer is usually a female friend or relative of the woman in labour, and her dance includes the dressing of a bundle of cloth to represent an infant. She dances with this dummy and then places it in the type of cradle which Kayan women usually carry on their backs.20

INITIATION

Initiation of girls in Africa is always accompanied by dancing. Among the Yao the girls who have reached puberty are anointed with oil, their heads are shaved and they are dressed in bark cloth. The festivities are opened by drumming in a peculiar and characteristic cadence, in response to which a closely packed body of people form up for the dance. The whole proceeding is called ‘being danced into womanhood.’21

Dancing is indispensable for the initiation of boys, and is resorted to even by very primitive people like the Andamanese, who have no musical instruments. Three men and a young woman all decorated with brightly coloured clay dance round the novice at the ceremonial feasts. The man at the sounding-board sings a song for which he beats time with his foot. The women help by singing the chorus and clapping their hands on their thighs. Each dancer flexes his hips so that his back is nearly horizontal, then with bent knees he leaps from the ground with both feet. At the conclusion of the dance, the novice receives a new name, and henceforth it is considered insulting to use his boyish title.22

SEXUAL SELECTION AND MARRIAGE

In Hawaii and other Polynesian islands the daughters of chiefs used to give an exhibition dance designed to attract the attention of eligible young men of rank and station.23 There were many kinds of dances, says an early missionary – ‘all too indelicate or obscene to be noticed.’24

Among the Bagesu of Mount Elgon, Uganda, a different method of ‘mate selection’ occurs. During their harvest festival, generally held at new moon, there is a dancing ceremony which continues throughout the night, accompanied by free beer and free love. It is during these nocturnal dances that men and women customarily arrange their marriages.25 In this instance it is clear that the harvest festival custom, originally intended to influence the fertility of the soil, has been extended to influence human fecundity. When it comes to celebrating the actual wedding, the role of dancing, along with singing and feasting, is so well known in simple societies that it does not need any special elaboration here.

SECRET SOCIETY

In Torres Strait, youths being initiated into a secret society witness for the first time the sacred dances and learn some of the legends of their tribe. The mask of the first dancer has no eye openings, so the second one has to guide him with a piece of rope. In dancing each foot is raised high before it is brought to the ground, and there are long pauses between the steps. Dancers emerge from a sacred house wearing masks, and dance into the horseshoe group of men, then back again into the house, repeating the performance twice. When returning, the dancers kick out as if trying to drive something away.26

WAR

In primitive societies, the war-dance is essential for strengthening communal bonds and for arousing the appropriate mental attitude for battle. Vivid accounts exist of the war dances of the head hunters in Melanesia and Polynesia. In Prince of Wales Island (Muralug), Torres Strait, the dance was performed after dark on a sandy shore fringed with mangrove swamps.

Near the fire sat the primitive orchestra, beating their drums in rhythmic monotone . . . from the distance, swarthy forms appeared, advancing in sinuous line as if on the warpath, every movement being timed to the throb of the drums . . . each dancer had painted the lower part of his body black and the upper part red, while the ankles were adorned with yellow leaves . . . No incident of the war-path was omitted. There was skipping quickly from cover to cover, stealthy stealing, and a sudden encounter of the foe with a loud ‘WAHU!’ All the dancers raised their right legs, and with exultant cries went through the movement of decapitating a foe with their bamboo knives. . . .27

In one form or another, sometimes more, sometimes less intense, the war-dance can be traced throughout the world. Frequently it takes the form of meetings of warriors and provides a remarkable example of the power of suggestion, imitation and contagious excitement. Everywhere it se...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Contents

- Preface

- I Introduction

- PART I: BACKGROUND

- II Anthropological Perspectives

- III Psycho-Pathological Perspectives

- PART II: SOCIO-HISTORICAL STUDY

- IV Medieval England – Thirteenth to Mid-fifteenth Century

- V Early Tudor England – 1485 to 1558

- VI Elizabethan England – 1558 to 1603

- VII Seventeenth-Century England

- VIII Eighteenth-Century England

- IX Nineteenth-Century England

- X Twentieth-Century England

- XI The Twenties: 1920 to 1930

- XII The Thirties: 1930 to 1940

- XIII The Forties: 1940 to 1950, World War II and Aftermath

- XIV The Fifties: 1950 to 1960

- XV The Sixties: 1960 to 1969

- XVI Summary

- PART III: SURVEY

- XVII Preface to the Survey

- XVIII The Survey: Young People – Enquiry into Present- day Dancing Habits and Attitudes

- XIX An Integration of Social Theory and Research Overall Conclusions

- PART: IV APPENDICES

- A Table of Dates

- B Copeland’s Manner of dancynge of bace dances. Extracts

- C Arbeau’s Orchésographie. Extracts

- D Cellarius’ Fashionable Dancing

- E Nineteenth Century Popular Assembly Rooms. Programmes and advertisements

- F Standardization of Ballroom Dancing

- G The Tango: Historical Background

- H ‘Old Time’ Dance Programme

- I Jamaican ‘Ska’ or ‘Blue Beat’

- J Survey Results (Tables 2–32)

- K Survey Questionnaire

- L Eysenck Personality Inventory (Sample questions)

- Notes

- Index