![]()

1 What Good Little Girls and Boys Are Made Of

The form of wood, for instance, is altered, by making a table out of it. Yet, for all that the table continues to be that common, everyday thing, wood. But, so soon as it steps forth as a commodity, it is changed into something transcendent. It not only stands with its feet on the ground, but, in relation to all other commodities, it stands on its head, and evolves out of its Wooden brain grotesque ideas far more wonderful than “tableturning” ever was.

Karl Marx, Capital

“I’m sick of always being a puppet!” cried Pinocchio, slapping his wooden head. “It’s about time I became a man, like other people!”

Carlo Collodi, Pinocchio

Before we can discuss how children are manipulated through their bodies we must address the concept of agency and the materials of youth—that is, object-relations from a materialist perspective. What are good children made of? Moving parts and a bit of magic? Stephen Benson writes that “the fairy tale is a medium for a putatively timeless message of good behavior” (2003: 155). Suzanne Stewart-Steinberg points out that Carlo Collodi’s Pinocchio learns from the blue fairy that he must be a good boy to become a man—the Italian ragazzino perbene meaning “a real or proper, but also upstanding boy” (2007: 21). In contrast, Disney’s Pinocchio is on a quest to become real, reified as an eternal boy, not a man. Nicholas Sammond explains,

Walt Disney appeared as a combination of two of the characters from Pinocchio (1940), Gepetto and Jiminy Cricket. He was part good-natured toy-maker, providing simple amusements and asking only that the children he helped to make become real boys and girls. (2005: 77, my emphasis)

This impossible ideal of fixed childhood, imposed upon children by the Disney industry, is mocked in Bill Willingham’s comic, Fables: Legends in Exile (2002), in which Pinocchio complains that he wants to find “Blue Fairy, who turned me into a real boy . . . and I’m going to kick her pretty azure ass. . . . [because] Who knew I’d have to stay a boy forever? The ditzy bitch interpreted my wish too literally” (87).

Ann Lawson Lucas points out that “there is no Fairy in [Collodi’s] first, brief version of the tale: the embryo of the character, in his last chapter, is only a ‘Little Girl’” (2006: 105). Stephen Benson clarifies,

the Fairy combines characteristics of the literary fairy tale stepmother and godmother, an example of the story’s fusion of fantasy with a didactic reality deemed necessary for educating the young in the newly unified Italian state. Indeed, the fantasy element is given a markedly un-Romantic reading in Pinocchio. (2003: 160)

In fact, for these reasons Nicholas J. Perella described the tales as distinctly “anti-Cinderella” (qtd. in Benson 161). But in the U.S. we love a good Cinderella story, especially for the rags to riches possibilities so implausibly seen in “The Three Fairies” as well. The quality Marjorie Swann highlights in early folklore, in which “ordinary people could aspire to new wealth not by engaging in protocapitalist trade or commerce, but rather by fulfilling their humble social roles” (and wishing for a fairy’s help) has proven popular and useful to Americans recasting old lore for kids (2000: 453). So Pinocchio has been made over often.

In the capitalist U.S., where Pinocchio has been reshaped to fit into the consumerist culture we know today, the socio-economic relations determining childhood as a generalized position have altered profoundly since Collodi’s time, no less profoundly affecting the potential agency of that position. Daniel Thomas Cook writes, in The Commodification of Childhood (2004), that “the trajectory of childhood, generally understood as [a] movement from dependence to independence, makes the extent of a child’s personal autonomy indeterminate at any given point” (13). Such conceptualizing allows for many trajectories wherein “the child marks out a semantic space where the question of the locus of power and volition, of who has the right and wherewithal to make decisions, is continually negotiated and renegotiated” (14). Thus, measured according to child autonomy, pedagogies are dichotomized as either child-centered or adult-centered; legal activism is characterized as defending self-determination rights or nurturance rights; child-rearing philosophies fall somewhere between necessary wastage and selfless/disinterested parenting. Viviana Zelizer characterizes the early twentieth century as a time when predominance noticeably shifted from the former extremes to the latter in the United States, and she adds another trajectory in economic terms: children losing economic value in the public sphere but gaining sentimental value within the family (as opposed to being unified by financial interdependence):

The twentieth-century family was defined as a sentimental institution . . . Yet, even the family seemed to capitulate to the dominant cash nexus, as the value of its most precious member, the sacred child, was now routinely converted into its monetary equivalent. Had the child lost its economic value only to become another commercial commodity? (1985: 211)

Nicholas Sammond delves into this and other questions in his Babes in Tomorrowland: Walt Disney and the Making of the American Child (2005), where he argues:

The subtle relationship between the child and the things it consumes is one in which the child appears natural in relation to the culture it absorbs through media commodities, so that the values it imbibes may appear in its adult future relatively unadulterated by rational apprehension. . . . Viewed in this light, both the child and its media are commodity fetishes, mystified tokens of powerful social forces, deployed in a common metaphysical operation of ‘social construction’. (363)

Certainly the relationship between children and things has been explored for centuries in toy fictions, and it is useful to superimpose these trajectories in reading the cultural shift from viewing children as self-learners to recipients, responsible participants to innocents, potential workers to prolonged dependents. This shift has as much to do with class as history—as the middle class grew in size and affluence during industrialization, so did the hegemony of a protectionist attitude toward children. Susan Stewart puts these narratives of control in the context of industrialization:

We are thrilled and frightened by the mechanical toy because it presents the possibility of a self-invoking fiction, a fiction which exists independent of human signifying processes. Here is the dream of the impeccable robot that has haunted the West at least since the advent of the industrial revolution. The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries mark the heyday of the automaton, just as they mark the mechanization of labor. (1993: 57)

From the height of industrialization in the U.S., through the first half of the twentieth century, toy fiction could be seen as exemplifying the transition from this tradition/tendency, as the nation’s economy became increasingly industrialized and mechanized for scale, then service-oriented. The latter part of the twentieth and the beginning of the twenty-first century are marked by a pervasive post-industrial theme of manufactured agency for commodified subjects-turned-objects (defined in contrast to objectsturned-imaginary-subjects).

Toy fictions make these themes and consumer culture anxieties explicit for an assumed audience of children. Puppets, enlivened toys/dolls, animated objects, all speak to needs for co-opting children into an ideology of conditional empowerment and perpetual commodification as imagined through a passifying gaze. Mikhail Bakhtin has written that the “theme of the marionette plays an important part in Romanticism,” where “the accent is placed on the puppet as the victim of alien inhuman force, which rules over men by turning them into marionettes” (40). Suzanne Stewart-Steinberg writes, “Carlo Collodi’s Pinocchio directly engages Yorick’s1 claim that the modern mechanical age would both kill the puppet and give birth to a new man so disciplined and manageable that he would be indistinguishable from his wooden predecessor” (2007: 38). It is significant that Collodi chose to represent such a malleable political subject in the figuration of a gullible puppet-child. Stewart-Steinberg explains,

It is then no coincidence that the nature of Pinocchio’s movement is so strange, for he is both a puppet who moves at the behest of another and an autonomous being who has no strings attached. . . . his looseness hinges on the construction of a social subject who is nevertheless conceived in terms of his puppet-like status. In other words, such a subject is nothing but an effect, bespeaking thus an anxiety about what may lie inside the subject beyond a piece of wood. (19, emphasis in original)

Pinocchio’s transformation in American versions of his adventures remains consistent with this passifying function in puppet motifs and a growing protectionist outlook on childhood. In this chapter I will look at a broad selection of animation narratives in order to show the expansive complexity and pervasiveness of this theme, using Pinocchio stories as a framing reference and contrast.

Jack Zipes’s characterization of the function of fairy tales in consumer capitalism makes the focal context of my study:

[O]fficial traditions intended to celebrate nation-states, religions, legal systems, and local customs . . . are set up to remain stable and eternal, while people are conditioned to become flexible and expendable to serve the needs of the advanced capitalist economic system. . . . We are expected to hold ourselves together and to be held together through artificial theme parks that make fakelore out of folklore . . . through schools that foster rote learning and positivist testing; through storytellers who espouse the value of traditional tales without critically examining what tales they are telling and why . . . and through political speeches that use false patriotic appeals to tradition so that the young will sacrifice their minds and bodies for their alleged native country, as though national identity were essential and innate. (2006b: 231)

As mentioned in my introduction, nationalism (even the false variety Zipes describes) lies at the heart of early folklore scholarship and fairy-tale collecting. Pinocchio was not only important to constructing Italian identity in Italy, but the figure and his adventures have been used to address notions of Americanness in the U.S., particularly for constructing immigrant identity in the consumer age. Nicolas Sammond explains, “What makes [Disney’s] Pinocchio (1940) an apt metaphor for the metaphysics of midcentury American child-rearing” is that it is “ultimately an assimilationist fable” (2005: 377).2 The film addresses an audience at the cusp of shifting industrial consciousness and encourages assimilation to a particular view of nationhood (especially for recent immigrants) as well as childhood (especially for those who were actually being replaced by adult immigrants3 in the workforce, due to child-labor reforms and compulsory education).

Perhaps the most lasting indication of this assimilative function is Angelo Patri’s star theme from his 1928 Pinocchio in America, which seems to have been the inspiration for Ned Washington’s lyric “When you wish upon a star.” Patri’s Pinocchio sees a star in a dream:

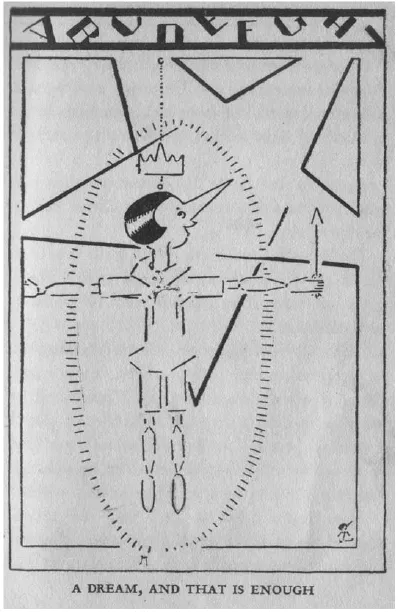

A star rose, a great burning star that called to him, ‘Pinocchio, I am your star. Rise, follow me to the Western world where lies your fame and fortune. Rise and follow me.’ An arrow came and fitted itself to his hand, and he sped it toward the star. He struck it fairly, and a shower of sparks fell about him, wrapping him in a mantle of light so that he shone like a radiant spirit. (1936: 5–6; see Figure 1.1)

Likewise, Disney’s Pinocchio opens to Jiminy Cricket singing, “If your heart is in your dream / No request is too extreme / When you wish upon a star / As dreamers do.” These famous words have become the Disney anthem and spell out a consumerist ideal of permitted passivity, where “Like a bolt out of the blue / Fate steps in and sees you through.” 4

The dominance of a passifying gaze is all the more transparent when you compare the 1940 film to the original story as conceptualized in 1882 by Carlo Collodi, in which Pinocchio is carved from an already living piece of wood that in its nascent block form speaks and even starts a fight between Geppetto and Mr. Antonio by shaking loose to hit his creator in the shin. The agency of Collodi’s puppet is unquestioned from (what is later described as) his “birth” (204). Yet, in the Disney version, Pinocchio is simply a lifeless marionette until a proven “good” man makes a sincere wish on a star that his lovingly crafted puppet come alive and be “a real boy.” In fact, the film explains Pinocchio’s agency as a temporary magical condition granted by the Blue Fairy in order to test his suitability for becoming real. Both Pinocchio’s sentient animation and, later, his authenticity, are the focal points of the plot development, whereas in the Italian original, such themes are less central, his agency being a foregone conclusion, and his becoming real being just one of many picaresque events.

Robert Coover’s hypertext, Pinocchio in Venice (1991), is both a novel about the older, sadder, and wiser Pinocchio (Professor Pinenut) and a critique of the earlier Disney adaptation. The professor explains that alterations to the story of his life were necessary for “the alleged infantilism of the American public” (1997: 96). Of the most significant revisions is the selfless depiction of his parental figures. To Pinenut’s memory, the depiction of his “grappa-crazed babbo” changed from a “heavy-handed illtempered father into a cuddly old feeble-minded saint. . . . The Disney film had captured something of Gepetto’s stupidity maybe, but not his malice” (218, 96). For the last half of the novel Pinenut struggles with his mother issues “toward the Blue Fairy, she who, whipping him with guilt and the pain of loss, has broken his spirit and bound him lifelong to a crazy dream, this cruel enchantment of human flesh. In effect, liberated from wood, he was imprisoned in metaphor” (289).

Figure 1.1 Mary Liddell for Angelo Patri’s Pinocchio in America. Doubleday, Doran, and Co., 1928.

Coover’s hypertext implicitly critiques Collodi’s original for an overdose of didacticism. As Maria Tatar has described it,

Collodi creates a world in which children are inherently lazy, disobedient, and dishonest—the same world we encountered in cautionary reward-and-punishment tales. At every bend in the road, evil forces . . . stand ready to seduce the child and to turn him into the little beast he really is. (1992: 75)

She concludes, then, that The Adventures of Pinocchio was “designed more to satisfy adults than children” (75). In contrast, however, Coover’s Pinocchio shows how, far from being a naughty boy, he was manipulated into paralyzing morality by a m...