![]()

Chapter One

Introduction

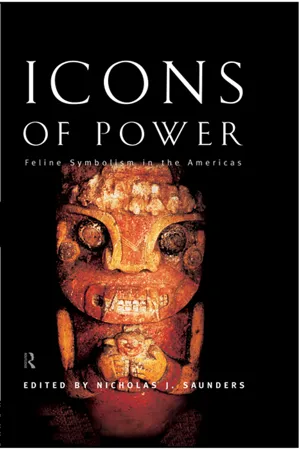

Icons of power

Nicholas J. Saunders

Origins and Perspectives

Felines have had a profound effect on human sensibilities since the beginning of recorded time. The lion, leopard, tiger, jaguar, and puma have evoked a diversity of cultural responses across the world, and throughout history. In art, myth, ideology, and religious belief, many societies have employed feline icons as metaphors to express human qualities and symbolize human relations.

Any meaningful analysis of feline imagery in the Americas should acknowledge that it is part of a wider appraisal of human-animal as well as human-feline relationships. The wealth of empirical detail and theoretical approaches contained in this volume adds greatly to our knowledge and understanding not only of American feline symbolism, but also of the diversity of ways in which human societies situate and represent themselves in relation to the natural and social worlds they inhabit.

In considering the question 'why the feline?' several points should be made. Significantly, apart from humans, felines are the most widespread and successful land-bound predators that evolution has produced (Kurten 1988:60-1). In almost every region of the world that humans colonized, they came into competition with large felines - the most specialized of living carnivores (Kitchener 1991:70) - already present, and superbly adapted to their physical environment. As Schaller and Lowther (1969:307) have noted, selective processes that shaped human society may have been more applicable to predators which were ecologically but not necessarily phylogenetically similar.

More specifically, as dangerous and effective predators (and scavengers), felines had already competed with, and, it appears, preyed upon, early hominids, for several million years (Brain 1981:266-74, figures 220, 221, 222). The origins and development of hominid cognitive processes may have been influenced by their inescapable interaction with predators which, by comparison, were stronger, faster, more agile, and equipped with deadly natural weaponry.

The impressive physical qualities of felines suggests that they are one of Mundkur's 'few select species ... [which] ... induced primeval man's hallucinatory imageries and instrinsically religiose sentiments eons before ritual and cult gave form or distinctiveness to his religions' (1988:146). Such a view may account for the almost universal fear, respect, and admiration which felines have elicited, and the widespread and often apparently similar kinds of symbolic and ritual attributes accorded to them throughout the world.

Representations of felines appear for the first time around 30,000 years ago, in the repertoire of European Upper Paleolithic cave art (for example Chauvet et al. 1996; Ucko and Rosenfeld 1967:54, figure 26; and see Mundkur 1988:165-6); images of maneless lions appear, for example, in the 'Chambre des Felins' at Lascaux (Leroi-Gourhan 1984:192-3). Whatever else such images meant to those who produced them, the discovery of a mammoth-ivory carving of a 'lion'-headed therianthrope from Höhlenstein-Stadel in Germany is presumably an indication of the capacity for symbolic thought exhibited by Aurignacian populations (Marshack 1989:333).

Archeology makes clear that by 6000 BC the feline is a recurring artistic motif, for example in the leopard imagery of Catal Hüyük in Turkey (Mellaart 1965:92-8). Around 4000 BC, tiger imagery appears in human burials at Xishuipo, China (Anon. 1988:36-7), and by 3000 BC feline images have been joined by textual evidence. The Sumerian goddess Innana (Ishtar) is described as a 'ferocious lioness' (Mundkur 1983:122), and the archetypal hero Gilgamesh, founder of kingship, engages in mortal combat with a lion as emblem of savagery (1983:122-3; Oates 1986:37, figure 20, 130-1, figures 87, 88). Not long after, the lion becomes the supernatural protector of, and metaphor for, Dynastic Egyptian royalty (Cassin 1981; de Wit 1951).

Subsequently, feline imagery appears in the mythology, art, and symbolism of Classical Greece (for example Bevan 1986:293-314; Rambo 1918; Vermeule 1972), associated with gods (Burkert 1990:149-50), heroes (Graves 1960:103-5), funerary monuments (for example Broneer 1941), and fabulous felinized creatures such as the sphinx, griffin, and chimaera (Bevan 1986:293-314). From Classical antiquity felines became heraldic creatures in Medieval Europe, and thence increasingly imperial icons amongst European colonial powers (see Saunders 1991, for an illustrated overview).

Such well known examples are pertinent to our theme for several reasons. The variety of Old World artistic images, mythic beliefs, and wider associations of feline symbolism coalesced over time to form an important part of a wider distinctive European view of nature by the fifteenth century - a view shaped by practical experience and superstition, as well as the influence of Christianity and the inherited Classical tradition. European attitudes to animals (Thomas 1983), exemplified in Medieval bestiaries - where the 'noble' lion had pride of place - saw them in a Cartesian light, as soul-less automata, in marked contrast to the worldviews of Amerindian (and many other indigenous) societies.

The pervasive influence of European views was such that it often masked the local significance of feline symbolism in other parts of the world, not least in Africa, southeast Asia, and the Americas. Ethnographic accounts gathered during the last one hundred years in particular have revealed a close symbolic relationship between large predatory felines, kings, chiefs, warriors and priests. One of the clearest examples of this relationship is among the Banyang of southeastern Nigeria, where the ritual of 'leopard-giving' - the leopard symbolizing male power - was a focal point for the display of constitutional politics (Ruel 1970:56). When a lion was killed in the Luapala valley (between Zambia and Zaire), purification rites required local leaders to step on the lion's skin in order to re-establish the monarch's 'dominion over lions' - the lions being metaphors for rival headmen and chiefs (1970:53).

In East Africa, 'Lion Men' societies (often acting as paid assassins) were active well into the twentieth century (Guggisberg 1961:256-77), and in West Africa, leopards were associated with royalty (McCall 1973:131-5), and with beliefs concerning human-animal transformations (Lindskog 1954:25). Similar supernatural associations are evident among the Batek Negrito of Peninsular Malaysia, where tiger-spirits are believed to take control of the shaman and cause him to growl and act like a tiger (Endicott 1979:139). The Batek are highly ambivalent towards tigers, which they greatly admire for their awesome strength and speed: qualities which make the animal an appropriate symbol for the notion of superhuman power on earth as personified by the shaman (1979:141). Up until the end of the nineteenth century, the tiger was considered the most important symbol of rank and power in Tibet (Lipton 1988:15, figures 5, 6), an echo, perhaps, of the once widespread symbolic association between tiger imagery and political authority in China (Chang 1983:60-3, 75).

Two important points emerge from the above. First, feline symbolism in the Americas can be seen from a virtually global perspective; this is a powerful comparative interpretive aid, though should not be taken to suggest that similarities of appearance indicate convergences of meaning or history. Second, the Old World 'tradition' of the significance of felines was brought wholesale to the Americas from AD 1492 onwards, where, confronting local beliefs, it generated a rich variety of indigenous responses well into the colonial period (see Flamell, chapter 10; Legast, chapter 5; Roe, chapter 7; and Saunders, chapter 2; all in this volume).

Early European sources are full of reports (often relayed from indigenous informants) of areas infested with 'fierce lions and tigers' (that is, pumas and/or jaguars). These were usually taken at face value by Europeans as referring to the natural animals - though there were presumably many occasions when these referred in fact to human enemies, warriors, shamans, or malevolent spirit-animals. The loss of indigenous meaning and the construction of misleading western attitudes in this single example is only now being reassessed.

A Brief History of Interpretation

Previous attempts to analyze feline symbolism in the Americas have fallen into two distinct categories - those based on an analysis of form (for example Joralemon 1971:35-78; Kan 1972; Roe 1974; Rowe 1967), and those which have utilized ethnographic analogy (for example Furst 1968; Kano 1979; Reichel-Dolmatoff 1972; Roe 1982). Many investigations have been concerned less with the possible origins or significance of feline (usually jaguar and puma) symbolism per se, or with indigenous views concerning the living animals, than with the 'sophistication' and style of representations of felines, feline 'deities', or feline elements in the iconography of particular Pre-Columbian societies (for example Benson 1974; Coe 1972; Kubler 1972; Roe 1974; Tello 1960).

Previously, many formalist approaches assumed not only that a feline was present in art, either complete, or in part, but also identified that feline, often arbitrarily, as the jaguar (see Saunders, chapter 2 in this volume). Feline images - indeed any animal images - were considered a straightforward attempt by the artist to represent either the living animal, a fantastical animal deity composed of elements of the feline and other animals, or, often for unspe...