![]()

Chapter 1

Growth versus Environment Debate

Economic policies designed to promote growth have been implemented without considering their full environmental consequences, presumably on the assumption that these consequences would either take care of themselves or could be dealt with separately. These are serious consequences, and it has become clear today that economic development must be environmentally sustainable.

Dr. Manmohan Singh, Prime Minister of India International Workshop on Green National Accounting for India, in New Delhi, April 2, 2013

Buoyant economic growth exceeding 7 percent over the last decade has raised the tantalizing prospect that India could eliminate extensive poverty within a generation. Growth has been fueled by a strong momentum in investment reflecting rising productivity, healthy corporate profits, robust exports, and high business confidence. As a result of this unprecedented economic expansion, India has become, in purchasing power parity terms, the world’s third-largest economy, behind the United States and China. Even with the recent slowdown, some economists think India will grow faster than any other large country over the next 25 years.1 An implicit assumption behind these optimistic predictions is that the conditions that have made the current rapid growth possible will prevail in the future.2

Surprisingly, none of these assessments consider the environmental sustainability of growth or the impacts of ecosystem degradation on development outcomes. Economic expansion will be accompanied by rising demands on already scarce and often degraded natural resources (soils, fossil fuels, water, and forests) and a growing pollution footprint that impacts negatively on human health and growth prospects.

Will the quest for high growth result in unacceptable environmental loss that will ultimately impede poverty alleviation? Should India grow now and clean up later? Where might the balance lie between rising gross domestic product (GDP) and declining environmental assets? This study seeks to address these fundamental questions, which are important because they concern the sustainability of India’s current development trajectory. This study provides an assessment of environmental changes and development impacts that can help define priorities and environmental management strategies.

1.1 The Environmental Challenges of Rapid Growth

Economic growth is universally recognized as a prerequisite for development. In India economic growth added eight million jobs every year between the early 1990s and 2004–2005 and allowed millions to emerge from poverty.3 The national poverty ratio halved over this period (National Institute of Rural Development, 2003), and by some estimates 300 million have joined the middle class with an income of at least US$7,000 per year.4

India’s remarkable growth record has been clouded by a degrading environment and growing scarcity of natural resources. Mirroring the size and diversity of the nation’s economy, environmental risks are wide ranging and are driven by both poverty and prosperity. Much of the burden of growth and development is falling upon the country’s natural assets and its people.

In a recent survey of 132 countries whose environments were surveyed, India ranked 125th overall and last in the “Air Pollution (effects on human health)” category.5 The study concluded that India has the worst air pollution in the entire world, beating China, Pakistan, Nepal, and Bangladesh. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) recent Global Burden of Disease assessment estimates that outdoor air pollution causes 620,000 premature deaths per year in India, a sixfold increase since 2000. The main cause is growing levels of particulate emissions (PM10) from transport and power plants. Also, according to the WHO, across the G-20 economies, 13 of the 20 most polluted cities are in India, and more than 50 percent of the sites studied across India had critical levels of PM10 pollution. A recent rapid survey by the Delhi-based Centre for Science and Environment revealed that almost 75 percent of respondents considered air pollution to be a major cause of concern and responsible for respiratory illnesses.

Simultaneously, poverty remains both a cause and a consequence of resource degradation: agricultural yields are lower on degraded land, and when forests are depleted, livelihood resources decline. To subsist, the poor are compelled to mine and overuse the limited resources available to them, creating a downward spiral of impoverishment and environmental degradation. The problem is most visible in the lagging regions of India, where rural poverty has become intertwined with resource degradation.

Much of the ongoing loss of natural assets can be attributed to the lack of incentives and markets to provide compensation for the supply of essential environmental services, including hydrological services, carbon services, and biodiversity. There is, however, a growing recognition of the importance of these resources in the public domain.6

Environmental sustainability could become the next major challenge as India surges along its growth trajectory. Three striking messages emerge from this overview. First, most measured environmental indicators exhibit negative trends throughout the country and raise concerns about the effectiveness of the environmental policy regime and the efficiency of resource use. Especially noteworthy are declining water quality and increasing water scarcity, increases in cities with high and critical levels of air pollution (PM10), forest quality degradation and biodiversity loss, and land degradation. Second, environmental degradation has development impacts, suggesting that the management of environmental risks must be an important part of a growth strategy (see Box 1.1). Third, the unstoppable trends of urbanization, population growth, and industrialization mean that these environmental pressures are unlikely to abate for many decades.

Box 1.1 Development versus the Environment: Trade-Off or False Dichotomy?

Discussions of environmental problems in India mirror a long-standing debate on whether countries should focus on growth until poverty is eliminated. The position that they should is based on the view that environmental resources are a “luxury” that will be demanded (and affordable) as incomes rise with economic growth. It suggests that developing countries such as India should first accelerate economic growth and fix the environment at some time in the future. The “grow now, clean up later” doctrine, though much debated, is now widely discredited by the experiences of many developing countries.

At one extreme of this prolonged debate are reports that have emphasized the finiteness of resources and the limited capacity of the earth to absorb pollutants. The doomsday predictions reached particular prominence in the Club of Rome report The Limits to Growth (1972). The report looked at current trends of resource consumption and projected these into the future. It predicted that scarcity would lead to economic catastrophe by about 2020. However, there are no signs of economic collapse. The problem with the prediction is that the report neglected the important role of markets in assuring efficient resource allocation. When scarcity emerges, prices rise, consumption declines, and alternatives (substitutes) are found.

The next major global report was Our Common Future (1987) by the Brundtland Commission. It refrained from dramatic predictions but highlighted the degradation of the global commons, biodiversity, and other life-sustaining, nonmarketed assets. There are two main channels through which environmental factors could encumber growth. First is environmental quality—safe water and breathable air are among the benefits that development attempts to bring. If the benefits from growth are offset by these higher costs, the environmental impacts will retard development. Second, environmental damage can undermine productivity—soils, aquifers, forests, and ecosystems are all vital inputs needed to sustain economic activity. Resources that are depleted for current growth can jeopardize future economic prospects. The Brundtland report emphasized the role of market failure and the need for policies to address these issues in ways that are equitable and efficient. These are problems that still remain unresolved.

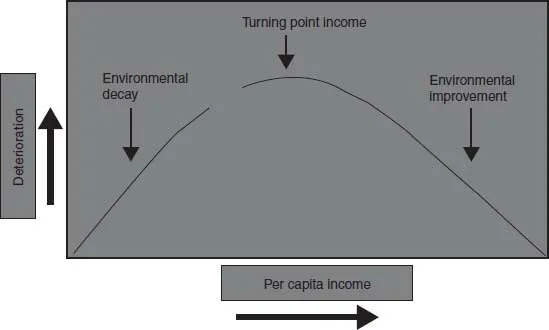

The most optimistic rebuttal to these reports came from an empirical relationship called the environmental Kuznets curve. Its proponents argued that global evidence showed that environmental degradation was just a matter of “growing pains” that would disappear with prosperity. This stylized fact is illustrated in Figure 1.1. The intuition of this statistical relationship may seem compelling. As an economy grows, the first issue to be addressed could be safe water—a major health hazard; next in line might be air pollution, a less visible but important health hazard; and somewhere in the future, biodiversity could be considered.

Whether this inverted U-shaped relationship between environmental quality and income levels actually holds in practice has been much debated in recent years. Most devastating for the proponents of the environmental Kuznets curve are findings from recent statistical analyses showing that the early estimates on which optimism was based were “spurious” (i.e., based on an invalid inference due to trending data). A significant finding that emerges from the literature is that the income-environment relationship is a matter of policy choice and is not predetermined. Good policies and effective institutions can deliver both higher incomes and a sustainable environment.

Figure 1.1 Environmental Kuznets Curve

Climate change poses an additional risk to long-term development prospects. It is projected that by the middle of the 21st century, the mean annual temperature in India will have increased 1.1–2.3°C under the moderate climate change scenarios (as per the A1B scenario of the IPCC).7 All the global circulation models project that precipitation intensity8 and heavy precipitation9 events will increase, suggesting greater variability in rainfall.10 The overall implication is that agro-climatic conditions will generally deteriorate across the country. The worst affected areas likely will be the arid and semiarid areas where agriculture is already under climate stress. Many of the major cities—Mumbai, Kolkata, Kochi, and Chennai—are located in low-lying coastal areas. Rising sea levels could disrupt economic activity, as well as the lives of some 100 million people living along the coastal belt. Further, striking impacts are likely to come from the melting Himalayan glaciers, which sustain agriculture and industry through the Gangetic plains.

1.2 Progress So Far

India has made substantial efforts in attempting to address environmental problems. The country has done many things right. It has enacted stringent environmental legislation and has created institutions to monitor and enforce legislation. There have been large-scale efforts to stabilize forest cover through afforestation schemes and considerable investments in water quality. India has enacted the National Environmental Policy (NEP), which recognizes the value of harnessing market forces and incentives as part of the regulatory approach.

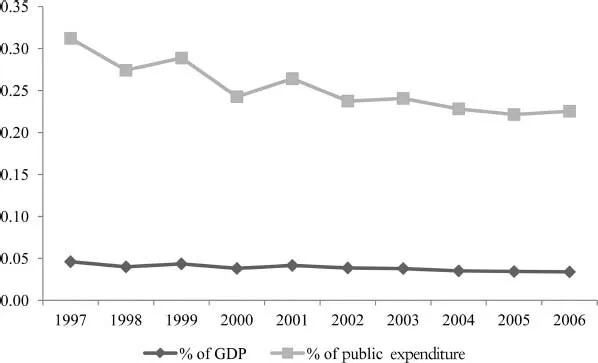

Yet responses have not been commensurate with the scale of the challenge. The pace of change has undermined these investments in environmental protection. There are clear signs that keeping up with the environmental challenges of rapid urban growth, industrialization, and infrastructure development is proving to be a difficult task. Despite comprehensive environmental laws and severe penalties for violating pollution standards, offenders are seldom brought to justice. It is no surprise that in the absence of credible deterrents, enforcement of environmental laws remains weak. The relative outlay of government spending for the environment has also stagnated (see Figure 1.2). It has remained constant as a share of GDP and has been declining as a share of total public expenditure, even though pressures on the environment have been growing. The efficacy of environmental regulation has been further weakened by an overreliance on command and control policies that are conducive to rent-seeking behavior.

Although economic growth may create environmental pressures, the solution does not lie in slower growth. In India economic growth has helped create many of the preconditions for sound environmental management practices that have been adopted across the country, and it has generated the policy space to address issues of sustainability. Policies for stronger growth often complement those for environmental protection—such as investments in clean water and sanitation or increases in the efficiency of resource use, particularly of common-property assets such as forests and shared water resources. Other problems are often exacerbated by economic expansion such as industrial pollution and the destruction of natural habitats. Here the challenge is to build incentives to address the environmental damage or externalities.

Figure 1.2 Plan outlay for environment as a share of GDP and total public expenditure

Source: World development indicators, World Bank (2010).

1.3 Study Objectives a...