- 296 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Chloroform, telegraphy, steamships and rifles were distinctly modern features of the Crimean War. Covered by a large corps of reporters, illustrators and cameramen, it also became the first media war in history. For the benefit of the ubiquitous artists and correspondents, both the domestic events were carefully staged, giving the Crimean War an aesthetically alluring, even spectacular character.

With their exclusive focus on written sources, historians have consistently overlooked this visual dimension of the Crimean War. Photo-historian Ulrich Keller challenges the traditional literary bias by drawing on a wealth of pictorial materials from scientific diagrams to photographs, press illustration and academic painting. The result is a new and different historical account which emphasizes the careful aesthetic scripting of the war for popular mass consumption at home.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Ultimate Spectacle by Ulrich Keller in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

“Vauxhall is Far Prettier”

Narrative and Visual Scenarios

Viewing the War

“It was the last battle of the old order. We went into action in all our finery, with colours flying and bands playing.”11

With these nostalgic words General Earle remembered the Battle of the Alma decades after the British army had evacuated the Crimea. Writing at a time of khaki uniforms and machine guns he had good reason to construe the Crimean War as a last war: an eminently picturesque war, that is; one which, by implication, had still been fun to wage. And quite possibly, to the extent that war is cheering, drums and flags, its last hurrah may have been heard in 1854 on the Crimean plains. Contemporary depictions, such as Edmund Walker’s painting in color pl. I, highlight the splendid sight offered by the British regiments at the Alma.

Sights change with distance, though; both the lithographic print, quickly executed in London on the basis of the first press reports, and the general’s words, spoken in retrospect from a high social station, commemorated the battle across a large spatial and temporal distance. Closeup views, while comparatively rare, are available to us, too. “I will not attempt to describe the sight, as it is too disgusting,” wrote a private soldier from the battlefield of the Alma, “but I never wish to see the like again. It certainly looked grand from the distance; when it commenced I was a long way in the rear, but as we advanced and came among the dead it became awful. I cannot describe my feelings at seeing so many poor souls lying dead, and the cries and groans of the wounded.”12 A water-color made by George Campion from an authentic sketch of the aftermath of the battle can serve as a close, though not very close, reminder of the private’s experience (color pl. II).

Contemporaries were torn between the two conflicting ways of looking at the battle — and the war as a whole, for that matter. “It is with field-glasses, not prying microscopes, that people must watch a campaign,” demanded Kinglake, the celebrated historian and apologist of the British war effort.13 By contrast, Lord Panmure, the Secretary of War in an embattled government, urged a medical commissioner leaving for the East: “It is expected that you will not content yourself with the simple dissection of the subject, and the demonstration of the morbid parts, but that you will subject them to microscopical examination.” While this was said not metaphorically, but literally, to a pathologist routinely making use of optical instruments, the demand for close and detailed scrutiny was an inevitable part of ministerial instructions for the numerous Crimean commissions of inquiry. Nor should we forget that other contemporary observers, notably the new breed of press reporters, subscribed to similarly strict investigative principles. A rare combination, if not reconciliation, of the close and the long view is found in Major Sterling’s letters. “I never expect to see again,” he wrote, “so beautiful a sight as that attack at the Alma. The English moved as if they had been at a field-day. I do not think I said much [in previous letters] about that battle in the picturesque point of view. All the horrors of the dead, dying, and wounded put it out of my head at the time.”14

At the river Alma, it should be explained, a mighty Russian army was planted on top of a range of hills in a bid to block the allied French and British armies’ progress toward Sebastopol.15 Between the Alma with its sheltering bank and the Russian positions on the heights, made even more dominant by a field battery behind an earth wall, lay the wide-open hill-side which the British were forced to cross under incessant musket and artillery fire. After a first, swarming attack by the Light Division had been beaten back, the Guards regiments stepped in the breach to launch a second assault which seemed to follow reckless, if not foolish tactical principles. According to eyewitnesses and historians, the scarlet battalions “formed into line with as much precision and lack of hurry as if they had been on the parade ground;” in keeping with parade practice, “markers” were even put out to insure precise alignment. Then, “ceremoniously and with dignity,” led by colonels and brigadiers with drawn swords, the troops began to move up the slopes in a thin, mile-long double line.16 Round after round of Russian fire raked the infantry lines, but every gap was immediately closed, progressively shortening the front in width, while always presenting a solid target to the Russians. In the end, amazingly, the densely packed enemy columns were routed, the battery taken. Though just one battle episode among many, and probably not as decisive as Kinglake liked to think, the British charge was still a brilliant accomplishment by any military standards. Remarkably, though, the criterion of judgment was primarily aesthetic: in storming the heights the British troops had looked good. Even the army’s Chaplain-in-Chief, watching from afar, could not help but describe the victorious charge, in alliteration to the language of his profession, as “transcendentally beautiful.”17

As to the technical exigencies behind the brilliant appearance, the British tactics at the Alma typified an age of short-range, errant, slow, in short, of still quite rudimentary fire power. The old-fashioned Russian muskets could kill, but they were ineffective beyond 100 yards and unreliable even at a short distance. Infantry salvoes still had the subordinate function of harassing the enemy, but battles were decided at close quarters with the bayonet, as the advancing line clashed with the defending one. For the attack to be successful, a maximal “shock” effect had to be achieved though gapless marching formations, with bright uniforms and high helmets thrown in for psychological effect. Much of the desired shock was indeed purely visual and psychological: to receive without flinching the onrush of a gapless regimental phalanx required the cold-blooded discipline of well-drilled veterans.18 Had the Russians had rifles at the Alma, they would have annihilated the British regiments, but the use of muskets allowed the infantry tactics of the 18th century to triumph for the last time. General Earle was right to construe the Battle of the Alma as a “last” one on the basis of its picturesque complexion; even though other episodes suggest that “first” battles were waged in the Crimea, too.

On the slopes of the Alma a complex international conflict entered its decisive stage. Earlier, Russia had threatened to invade the weakening Ottoman empire. Britain and France aligned themselves with the Sultan and sent an expedition force to the Black Sea which eventually landed in the Crimea to conquer Sebastopol. Contrary to initial expectations, however, the victorious charge at the Alma was not followed by a swift attack on the town, but by a siege war in which the British and French troops found themselves occupying a few square miles of enemy land thousands of miles away from home19. (For a simplified birds-eye view of the siege see fig. 41.) It was a vulnerable position which was tested soon enough when a large Russian army pored into the plain behind the allied camps in an attempt to sever the invaders from their supply base. The ensuing battle is noteworthy for an episode in which weapons and appearances interacted in a new and different way compared to the Alma. In the course of the battle, the harbor of Balaklava, the British contingent’s lifeline, came under attack. As a massive Russian cavalry detachment advanced on the town, with the allied infantry helplessly looking on from the distant heights, the fate of the expedition rested with the 93rd Highlanders, deployed across the mouth of Balaklava valley, half-hidden in the deep grass behind a ridge. When the Russian cavalry had moved within 30 yards, the “Thin Red Line” (as it came to be celebrated in British historiography) suddenly stepped forward and fired three volleys, forcing the Russians to retreat in disarray.20 William Munro, the regimental surgeon, noted in his memoirs the general “surprise and disappointment” that the British fire “had done so little apparent execution amongst the charging cavalry, for scarce a dozen saddles were emptied.” But this was a deceptive impression, as Munro found out later upon meeting a crippled Russian cavalry officer who had led a squadron in the charge on Balaklava. According to him the British volleys had been very effective, indeed. “Almost every man and horse in our ranks was wounded,” including himself, he asserted, except that this was not apparent from a distance because the Russian saddles kept even a mortally injured hussar upright for some time.21

Munro had witnessed a moment in which the Crimean war revealed its modern face — upon closer inspection. The Highlanders were already supplied with relatively sophisticated rifles of the “Minié” type. Salvoes from this weapon were more powerful and accurate, and could be delivered in faster succession than musket fire.22

Before the century was out, the rifle’s ever-increasing destructiveness rendered picturesque cavalry attacks a glorious memory, whilst prompting radical changes in infantry tactics as well. The Battle of Balaklava, which also saw the notorious charge and annihilation of the Light Brigade, represents the swan song of the cavalry as a useful branch of the army; with it the equestrian prowess and social predominance of the aristocracy were destined to disappear. On the surface and from a distance still a splendid adventure, warfare had begun to be dominated by an increasingly powerful arms technology that made visibility a deadly flaw.

After a last open-field encounter at Inkermann on November 5 there were no further interruptions in the drudgery of the siege. The bravura of generals and soldiers became secondary to the competence of engineers designing trenches and artillery officers directing batteries — though the high expectations set in the concentration of fire-power proved as illusory before Sebastopol as it did 60 years later at the Somme. But again, the modernity of the trench war was not immediately apparent to the contemporaries. For many of them, especially those standing with field glasses in rear positions, the terror of the siege machinery remained hidden beneath a picturesque veil. Sorties and artillery duels at night held a particular aesthetic fascination which tended to be described in the romantic terminology of the sublime and the awesome. Lord Paget, for example, though usually a dry, pragmatic witness, resorts to rather exalted language in trying to convey

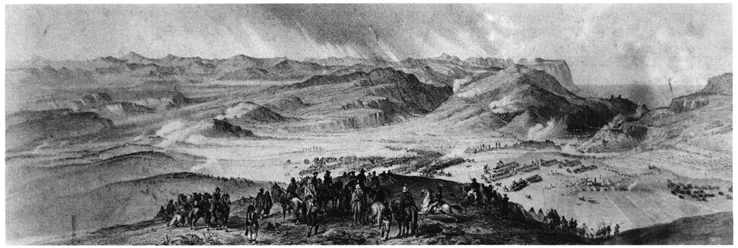

FIGURE 1 Balaklava, 25th October 1854, hand-colored lithograph by A. McClure after a drawing by Lt.-Col. Adye R.A. and Capt. Pupper R.H.A., published by Colnaghi, April 20, 1855, National Army Museum, London

“the grandeur and solemnity” of a trench battle, “when darkness reigns, when the flash of every gun illuminates the sky, and the aerial course of each shell is seen as it whirls its circles in the air.”23 Paget refers to the “second bombardment” of Sebastopol in April, 1855, which proved as futile as its predecessor and several further cannonades.

Though somewhat randomly selected, the few battle episodes recounted here can help to make a point. Like so many others the Crimean War was marked by tensions between military, technical and social tradition and innovation. Plumed hats and Minié rifles, flogging and chloroform, oxcarts and steamships, palatial battle painting and cheap press reportage were all strikingly contradictory features of the campaign. But it is the aesthetic dimension in which the particular historical signature of the war seems to have inscribed itself more clearly than elsewhere. Trying to probe beneath the picturesque surface quickly becomes an exercise in futility: Aesthetic factors enter the analysis at every point, until one realizes that the spectacular visual appeal of Crimean warfare forms one of its structural characteristics. Looking back through the filter of 20th century war experiences from Verdun to Vietnam it may sound frivolous, but like most historic wars, the one fought in the Crimea had a perversely beautiful aspect, among others; it required to be viewed and depicted in sophisticated ways, and the modalities of contemporary visual appreciation form an integral part of its history. Nor would it do to take the Spectacle of this war for a quaint and curious vestige of the past surviving marginally in spite of modern technological developments. Military display had been around for centuries, but it was innovations such as steam transportation, press reportage, tourism and modern habits of cultural consumption which gave the traditional visual symbolism a new lease on life and helped to construct martial spectacle on an unprecedented, technically enhanced scale.

Indeed, there is a good deal of evidence that the military events were methodically organized and conducted as spectacles to be seen from privileged viewpoints and calling for quasi-artistic connoisseurship of the various sights. William Russell, the Time’s celebrated correspondent before Sebastopol, adopts a telling metaphor in his description of the Battle of Balaklava — which was fought in the plains, but directed from a plateau commanding a splendid view of the action. “Lord Raglan, all his staff and escort, and groups of officers, the Zouaves, French generals and officers, and bodies of French infantry on the height,” Russell points out, “were spectators of...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Preface

- 1 “Vauxhall is Far Prettier” Narrative and visual scenarios

- 2 “Storm’d at With Shot and Shell” The heyday of lithography and the London shows

- 3 “Bastard of History, Only Much Truer” The ascendancy of picture reportage

- 4 “The Valley of the Shadow of Death” The triumph of photography

- 5 “My Nearest and Dearest” Home-front scenarios

- 6 “The Usual Plunging Horses” The swan-song of history painting

- 7 Conclusion

- References

- Bibliography

- Index