eBook - ePub

Studies in the Growth of Nineteenth Century Government

Gillian Sutherland, Gillian Sutherland

This is a test

Share book

- 316 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Studies in the Growth of Nineteenth Century Government

Gillian Sutherland, Gillian Sutherland

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The main theme of this book is the complex relationship between government servants and the world around them and this is explored in a number of ways. The essays include studies of the people who played an important part in the development of 19 th century government: there is a chapter on the transmission of Benthamite ideas, an ccount of John Stuart Mill and his views on utilitarianism and bureaucracy, and of the work of Charles Trevelyan on the Northcote-Trevelyan Report. The Treasury, the Colonial and Foreign Offices, the Labour Department of the Board of Trade are also examined in relation to government growth in the period.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Studies in the Growth of Nineteenth Century Government an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Studies in the Growth of Nineteenth Century Government by Gillian Sutherland, Gillian Sutherland in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 |

The Transmission of Benthamite Ideas 1820–50

The profound influence of Bentham’s arguments and models on the legislation of the nineteenth century is too well attested for me to elaborate here. There can be no doubt that the fields of colonial and Indian policy, of financial and fiscal policy, of penology and legal procedure, and of social policy and administration, were all fertilized by and to a considerable extent reshaped in accordance with the views of this extraordinary octogenarian. Brougham described him by saying ‘the age of law reform and the age of Jeremy Bentham are one and the same’.1 In 1843 John Hill Burton (the editor of his works) ascribed to him the authorship of twenty-five distinct reforms.2 In 1905 Dicey characterized by his name the whole legislative era stretching from 1825 to 1870.3 And while little contemporary research has even attempted let alone succeeded in challenging this purported pre-eminence, a number of specialized monographs have even more amply confirmed it.4

Therefore, I do not propose at all to establish the fields wherein Bentham’s views prevailed, and the varying degree in which they did so. My question is quite a different one. It may be put like this: given that the views of this man did indeed exert a profound effect on a wide range of matters, by what means did this come about? By what means were Bentham’s thoughts transmitted to those who were not merely willing to carry them into legislative effect, but able to do so? At one end of the process we find Bentham scribbling away in Queen’s Square Place. At the other end we find civil servants and judges busy executing his views. How did this come about?

That this simple, indeed, brutal question has not been put before is probably due to the muddled thinking of Dicey. He seemed to be asking this question. ‘Why did Benthamism obtain acceptance?’ he wrote.5 But his answer was: ‘It gave to reformers and indeed to educated Englishmen the guidance of which they were in need; it fell in with the spirit of the time.’6 Even Dicey recognized that this was no answer: it was, as he himself admitted, ‘Very general, not to say indefinite’. So he tried again, and produced four answers. ‘Benthamism met the wants of the day’—by which he meant that Bentham’s plans ‘corresponded to the best ideas of the English middle class’. Next—in his words—‘Utilitarianism was … “in the air”.’ Thirdly, ‘Benthamism fell in with the habitual conservatism of Englishmen.’ Finally, he concludes, ‘Legislative utilitarianism is nothing but systematized individualism and individualism has always found its natural home in England.’7

The reason that Dicey answered in vague generalities of this kind is because of his highly idiosyncratic view of what constituted Benthamism. On closer inspection this turns out to be not the creed of Bentham and his circle but a purported ‘commonsense Benthamism’, which in turn becomes simply ‘individualism’. This individualism, again, is alleged to be the common property of Whigs as much as Philosophic Radicals, of Conservatives as much as Whigs, and of working-class leaders as much as Conservatives!8 This is why Dicey alleged that the acceptance of Benthamism (as he called it) was ‘all but universal’. It was a creed held by everybody who was anybody. Hence his problem was to try to explain why it proved so overwhelmingly acceptable. And hence the large, vague generalities he offered by way of explanation.

My question is essentially different because it starts with a different view of Benthamism. To me Benthamism means the views of Bentham and his circle of intimates: i.e. the views comprehended by Halévy in his Philosophic Radicalism. From this it follows that the number of those who held these opinions was at all times very small. And from this we come back to my original question: how did the influence of this tiny number become so great as to effect the wide changes in law and administration ascribed to them?

Shortly, the answer I propose is this. I maintain that the translation of Bentham’s ideas into practical effect took place by a threefold process—or, better, by the interaction of three processes. I call these, respectively: IRRADIATION, SUSCITATION, PERMEATION.

IRRADIATION was the process by which small knots of Benthamites attracted into their salons, their committees and their associations a much wider circle of men whom they infected with some at least of their enthusiasms and thereby turned into what I might call Second-Degree Benthamites.

SUSCITATION needs a little more explanation. I had originally chosen the word Publicization; but on consulting the Shorter Oxford Dictionary, I found that such a word as SUSCITATION did exist. It exactly conveys what I mean: ‘To stir up; to excite [a rebellion, a feeling etc.]; to raise out of inactivity; to quicken, vivify, animate.’ SUSCITATION was the process of arranging public inquiries or the press or both together in such a way as to create a favourable public opinion, of a temporary kind, amid influential groups in the country.

PERMEATION was the process of securing official employment of oneself and thereafter using this position for further IRRADIATION—on one’s supporters and subordinates; and for further SUSCITATION also.

IRRADIATION made friends and influenced people. Through them, SUSCITATION proved possible. SUSCITATION led to official appointment and hence PERMEATION. And permeation led to further irradiation and suscitation; and so on da capo.

1 Irradiation

Exposure to the thought and attitudes of Benthamism took five main forms. One must not underrate, to begin with, the importance of the salon. In those days the intellectual élite formed a much narrower circle than today. To establish this one has only to compare a copy of Men of the Time for this period with a modern Who’s Who. In such circumstances personal contacts, through a salon, could powerfully affect the whole body of informed opinion. The immediate source of irradiation was of course Bentham’s own house. It has been said, by Dicey, that when explaining the hold that Benthamism took one must not forget the fact that he lived a very long time, and that therefore his views had the benefit of prolonged reiteration.9 Far more important is the fact that through this long life Bentham received a continuous stream of influential visitors. Few of them became wholehearted disciples, most of them—like Brougham for instance—adapting Bentham’s views to suit their own; but even fewer went away as confirmed opponents of his views and system. Apart from Queen’s Square Place, however, there were other such Benthamite salons. That of James Mill was particularly important. To some extent, his visitors overlapped Bentham’s; but many derived their Benthamism through him alone. A list of the more important of his friends reads like a Benthamite Roll of Honour. It includes Ricardo, Brougham, Joseph Hume, Francis Place, Romilly, Horner, William Allen, Grote, the Austins, Strutt, the Villiers brothers, Coulson, Fonblanque, Bickersteth, McCulloch, Black (of the Chronicle), Molesworth and Arnott.10 Now many of these formed their own ‘salons’ (if we may call them that). Thus there was a distinct ‘Grote clique’ to which both Charles Butler and Joseph Parkes belonged. Likewise Francis Place made contacts quite outside the range of James Mill’s own circle of friends.

Outsiders could also be irradiated in a second way, if they became part of the team writing for some Benthamite periodical. Contacts between editor and the contributors were very close. Thus Fonblanque refused to take over the editorship of the Examiner from Leigh Hunt unless he could bring Chadwick in as assistant editor; and when he had done so, we find Fonblanque, Chadwick and John Mill writing most of the journal between them. The teams contributing to a journal or periodical soon tended—as indeed they do today—to develop a corporate spirit. Thus the Westminster team consisted of Southern, Bowring, James Mill, Perronet Thompson, Charles Barker, W. J. Fox, Southwood Smith, J. A. Roebuck, William Ellis, James Hogg, the Austins, Chadwick, and of course John Mill. New contributors to the journal tended to fall under the spell of teams such as these. Bentham’s correspondence contains repeated references to efforts to found new periodicals—such as the Jurist of which Rosen was the editor. In so far as Bentham’s disciples produced and contributed to such periodicals as Companion to the Newspaper, the Westminster, the London Review, the Jurist, they constituted so many centres into whose orbits newcomers were attracted and in some cases retained.

Similar in operation and effect were the numerous committees established by the Benthamites. It was through the Greek Refugees Committee, on which Joseph Hume sat, that Bowring and (it appears) Chadwick first swam into the Benthamite orbit. The ‘Diffusion’ societies illustrate how Whig noblemen and merchants could be brought into contact with a nucleus of Benthamite disciples. The Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge founded in 1827 not only brought into the Benthamite circle two people who were to become disciples and propagandists—viz. Joseph Parkes, of Birmingham, and Charles Knight, the publisher: it associated these two men with Benthamites like James Mill and Hume on the one side, and with merchants like Josiah Wedgwood II, and young Whigs like Althorp and Russell on the other. The Society for the Diffusion of Practical Knowledge, founded in 1833, had a similar effect. Its moving figures were three confirmed Benthamites, Place, Roebuck and Hume; most of its financial backers were well-known Benthamites too; but it was able to attract others also such as Warburton, the timber merchant, and Olinthus Gregory, the mathematician and astronomer.

The irradiation of outsiders is best illustrated, however, by a fourth channel; the establishment of specialist societies. Of these the London Statistical Society and the Political Economy Club are the outstanding examples.

The Political Economy Club, founded in 1821 by James Mill and Thos. Tooke, was not an innocent self-improvement society. It was formed, in the first place, with the deliberate intention of propagating one particular school of political economy: that was the Ricardian system, as against that of Malthus and others, and as understood by James Mill and McCulloch. Professor Checkland, in his article on The Propagation of Ricardian Economics in England’11 has established this particular point definitively. Secondly it had an avowed propagandist intention. The Members of the Society’, said the Rules, ‘will regard their mutual instruction and the diffusion among others of first principles of Political Economy, as a real and important obligation.’ Furthermore, the Rules continue thus:12

As the press is the grand instrument for the diffusion of knowledge or of error, all the Members of this Society will regard it as incumbent upon them to watch carefully the proceedings of the Press, and to ascertain if any doctrine hostile to sound views on Political Economy has been propagated; to contribute whatever may be in their power to refute such erroneous doctrines and contravert their influence; and to avail themselves of every favourable opportunity for the publication of seasonable truths within the province of the society …

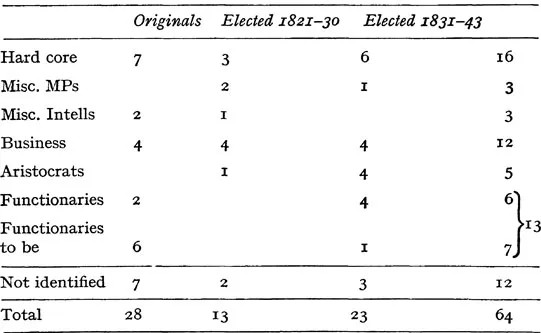

The original founding members numbered twenty-eight. Of the twenty-one identified, seven may be characterized as firm, first-degree Benthamites, e.g. James Mill, Grote, Ricardo, Tooke and the like. Two were miscellaneous intellectuals—Zachary Macaulay and Malthus, both brought in for special reasons. Four were businessmen, merchants and bankers. Two were civil servants. No less than six, however, were miscellaneous professional men: and of these, every one was to be given some government appointment between 1830 and 1840 when the Whigs were in power.

During the period 1821–30, eleven elections were made. Of the nine identified, three were Benthamites—Coulson, McCulloch and (with a certain query) Senior. Three miscellaneous MPs and/or intellectuals were brought in. The most significant elections, however, were among the businessmen and aristocrats. Among the four businessmen elected were Baring and Poulett Thomson. Both of these were to be at the Board of Trade during the Whig period of office and both were to give their patronage to Benthamite nominees. The sole aristocrat elected was Althorp: and as Whig Chancellor he was to be even more influential in opening the door to the Benthamites. For instance it was through him that Lefevre and Chadwick came into government service.

Between 1831 and 1841, there were twenty-three elections, of which twenty are identifiable. In this decade another six confirmed Benthamites were admitted—Chadwick and John Mill, Romilly and Perronet Thompson, for instance. The number of miscellaneous MPs and intellectuals fell to one. Four businessmen were admitted; among them J. Morrison and S. J. Lloyd (later Lord Overstone). The great difference between this and the earlier period lies, however, among the categories of aristocrats and functionaries. There was now a clear policy of bringing in aristocrats deemed likely to be influential: Villiers, Spring-Rice, Kerry, and above all, Lansdowne, were elected in this decade. Furthermore, one may also infer a novel practice of electing functionaries who appeared worth influencing: thus Deacon Hume, Holt Mackenzie, Sir George Graham and G. R. Porter were brought in.

The composite picture that emerges is of a small group (seven) of Benthamite propagandists who began by associating with themselves a small group of merchants and bankers and a larger group of intelligentsia; who were able, between 1821 and 1830, to influence three important Whigs, viz. Baring, Poulett Thomson and Lord Althorp; and who then had the satisfaction of seeing many of their original number—e.g. Tooke, Torrens, Parnell, Coulson, Senior and McCulloch—in office under the Whigs alongside their intelligentsia friends: and who finally, from this position of strength, brought in important aristocrats and civil servants. Of the sixteen first-degree Benthamites who were members between 1821 and 1841, two had died. Of the fourteen survivors in 1841, one had been a Minister; four were MPs and eight were civil servants or government commissioners. Of the businessmen, Baring and Thomson were of ministerial rank; and of the aristocrats, four were of ministerial rank. In addition, twelve other members were in the government’s service. To put this another way: in 1841 there survived sixty-one of the members elected during 1821–41. Of these, fourteen were first-degree Benthamites: seven members had held ministerial rank; eight were MPs and twenty were civil servants.

Political Economy Club

Statistical summary

The Lond...