- 380 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

An Introduction to Rural Settlement Planning (Routledge Revivals)

About this book

This book, first published in 1983, provided the first thorough and informative introduction to the theory, practice and politics of rural settlement planning. It surveys the conceptual and ideological leanings of those who have developed, implemented and revised rural settlement practice, and gives detailed analysis of planning documentation to assess the extent to which policies have been successfully implemented. Paul Cloke assesses the shortfalls of rural planning and resource management and suggests methods by which a sustainable rural future might be attained. This reissue provides essential background and a comprehensive handbook for those with an interest in rural settlement planning.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access An Introduction to Rural Settlement Planning (Routledge Revivals) by Paul Cloke in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ONE

Introduction

Rural planning has come of age. For too long, it has been branded the ‘poor relation’ of the more favoured urban aspects of town and country planning, which have been allowed to dominate the morale and image (both internal and external) of the rural branch of planning. It is certainly true that planning attention in the latter half of this century has been focused upon matters of urban blight, deprivation and renewal, while the social and economic problems of the countryside have received only half-hearted and unconsolidated consideration. It is equally important that the campaign for an equitable share of planning resources for rural environments should not be permitted to lapse into an acceptance of the current imbalanced state. However, the time has come to discard the use of this underemphasis as the major focus for rural planning, and to develop new cynosures which are more in keeping with the progressive and seminal needs of modern-day countryside problems.

Discernible progress has been achieved in rural planning over the last half century, as is witnessed by the excellent reviews successively assembled by Green (1971), Woodruffe (1976), Davidson and Wibberley (1977) and Gilg (1978). Equivalent summaries have been slower to materialize outside Britain, a notable exception being Lassey's (1977) treatise on countryside planning in North America. What emerges from this accumulation of information is that rural planning has been gradually transformed from a young art in the 1940s and 1950s into a developing political, social and economic science in the 1980s. Thirty years of land-use planning in the countryside, marked by the three distinct stages of the development plans, their reviews, and, more latterly, the structure plans, have proffered a wealth of experience in how and how not to impose management techniques on the allocation of rural resources. Concomitantly, there has been an upsurge of interest in rural planning both on the part of the general public and within the planning and education professions. An increased level of media exposure has led to a heightened awareness of rural problems, and ‘rural’ courses in geography, planning and other related disciplines are proving to be extremely popular in universities and polytechnics.

Within this overall development of rural planning, the specific study and practice of rural settlement planning has loomed large. During the post-war period, the planning of villages and towns in countryside areas has been subjected to a range of administrative, methodological, technical and political pressures and problems, the interaction of which has moulded rural settlement planning into its current state. Indeed, there is at present a lively debate amongst planning professionals and academics concerning the whole future of rural settlement planning. The whole political question of what management mechanisms are required to deal best with problems of the dying village at one extreme, and the booming suburban town at the other, is both current and pressing.

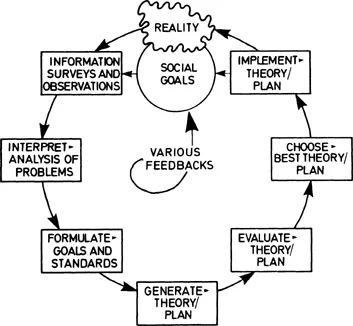

An illustration of the evolving nature of rural settlement planning may be gained from a contrast of orthodox and heterodox presentations of the planning system as seen in countryside areas. Figure 1.1 can perhaps be seen to represent a view of the system from the inside looking out. The adoption of a systems approach to planning, pioneered by McLoughlin (1969) and Chadwick (1971) has generated a series of standardized and generally accepted stages of the planning process, progressing from social goals, information retrieval and problem-analysis via various forms of plan-making to policy implementation and finally reality. Batty's (1979) version (figure 1.1) expresses planning as a cyclic process of science and design but essentially marks the current tide-mark of the orthodox modelling of planning by stages. Rural settlement planning has, until recently, been characterized by a loose adherence to this rather traditional genre.

Figure 1.1 The orthodox view of planning (inside looking out)

Source: Batty, 1979, 42

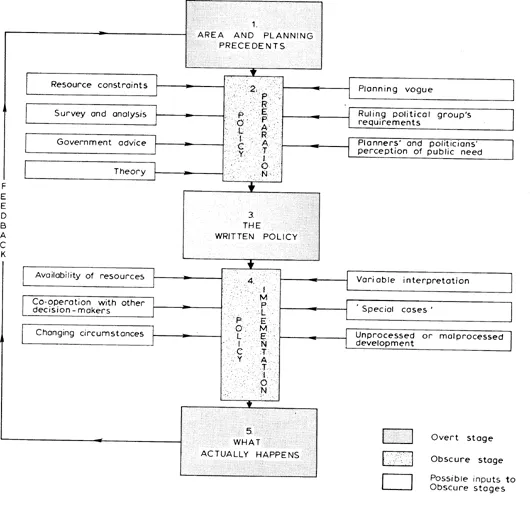

By contrast, a more heterodox view of the planning system is suggested in figure 1.2 which highlights more accurately the specific areas of guidance, influence and decision-making which shape rural settlement planning as it actually happens. The model is not designed to be a sceptical rejection of the orthodox per se, but rather a realignment from emphasis on stages to emphasis on causal factors, sparked by a view from outside of the rural planning system looking in. This would appear to be an equally valid approach with which to isolate the fundamental issues of rural settlement planning. The model is also useful because it can be applied both to the formal planning process and to wider systems of resource allocation and decision-making from which rural outcomes emerge. Figure 1.2 suggests a scheme of three overt and easily recognizable stages. These are linked by two obscure stages about which less is known but which fashion the following overt stages in the system.

Figure 1.2 The heterodox view of planning (outside looking in)

Area and planning precedents

The starting point for the generation of settlement planning policy in rural Britain has tended to be an assessment of previous policy, areal strategy and resource allocation, rather than the more utopian ideal of formulating social goals. Planning pragmatism will usually dictate that many entrenched policy dicta are to some extent honoured in successive plan considerations. At the local scale, this might mean that outstanding residential planning permissions will be the first input into the decision as to where additional housing will be permitted within a new plan period. Very few such permissions have been revoked in order to give new policy emphases a clean sheet to work from. On a more strategic level, those rural centres where growth in services and facilities has been encouraged during a previous regime are likely to receive continued development on the basis of the life-style opportunities already nurtured within these specific locations.

To recognize this transfer of commitment from one plan period to another is not necessarily to condone it as a basis for addressing contemporary rural problems through the allocation of resources. Indeed, it does appear that an acceptance of this ‘trend’ or ‘inertia’ planning is not only hindering the adoption of more radical policy solutions but is also ensuring that these less conventional approaches to problem solving will become increasingly difficult and expensive to transpose onto the deeply rooted established system of distribution. For example, a persistent strategy of concentrating services and facilities into rural growth centres will endow the alternative option of dispersing resources amongst the lower levels of the settlement hierarchy with an ever more extravagant image in the eyes of decision-makers and the agents of policy implementation. It may well be that rural settlement planning will only become more successful by allowing a clear statement of social goals to override all previous considerations, but it is important to note that at present these precedents do exist, are recognizable, and form an important limiting factor on subsequent policy preparation.

Policy preparation

The actual preparation of rural settlement planning policy consists of the interplay between several different variables. Of these, some are measurable and explicitly acknowledged in the resulting written policy, but others are intangible and act as covert influences on subsequent events. Some of these variables are listed in figure 1.2. For example, a major restricting factor on the scope with which alternative policies may be considered is the availability of financial resources for positive planning initiatives. All too often in the postwar period, planners have been compelled to resort to negative planning techniques and strategies of contraction simply because more positive policy options were barred by lack of finance at local, county and national levels. In this climate, planning alternatives are usually discussed in a framework of resource reallocation rather than resource increase.

Given this monetary straight-jacket, other tangible inputs to planning policy may be recognized. Survey and analysis techniques are of obvious importance to an assessment of trends and requirements in the area concerned. In the past, these surveys were preoccupied with demographic forecasts of in-migration or depopulation but more recently the housing, employment, transport and service requirements of existing populations have become increasingly emphasized, as has the need for public participation. In addition the influence of government advice (either by legislation or recommendation) is a crucial and definitive source of guidance in the policy presentation stage, while the impact of socio-economic, spatial or political theory is also relevant although less easy to monitor.

Alongside these easily recognizable factors, several surreptitious forces are also at work. For example, planners are often influenced by a certain vogue or strategic fashion in their assessment of alternative policy options. This may be partially underpinned by current government advice or theoretical leanings, but the diffusion of ideas from conferences and meetings is also important in the establishment of broadly favoured planning concepts. Another causal factor in the emergence of a particular policy direction is the political dogma (or at least the leanings) of the group controlling the planning and other committees of local authorities. This group can dictate the take-up rate of any permissive legislation from central government, and can also impose its own stamp on the overall planning strategy emanating from the policy preparation process. Finally, there is the question of how the various needs of rural areas are perceived and evaluated by both politicians and planners. Pocock and Hudson (1978, 134) stress that ‘planners as a social group possess environmental images that may differ from those whom they seek to influence or those who are affected by resource allocation’. The different images of rural need perceived by these three groups are yet other elements in the policy-preparation equation.

The written policy

The result of these various interactions during policy preparation is some form of documented statement of policy in different degrees of detail. The written policy acts as a fulcrum for the rural settlement planning process. It serves as a forum for agreement between conflicting political and professional elements who held opposing views during the preparatory planning manoeuvres. In effect, such ‘agreement’ is largely equivalent to the reasonings of the dominant political and administrative parties. The draft written policy allows for feedback on a ‘finished’ policy from individuals and groups within society, and the adopted statement is designed to give the public a clear and reasoned account of the nature and justification of policy decisions. Also pivoting on the written policy are the opportunities for a clear interpretation of agreed policy as documented in the official planning reports – an interpretation that will be used by prospective developers as well as planners – and the possibility for the ministry concerned to ensure that individual planning areas do not stray too far from the prescribed rulings of central government.

With all these roles to play, the importance of policy statements should not be underrated, but at the same time it should be remembered that the content of the written policy is totally dependent on the machinations of the plan preparation stage. Furthermore the nature of planning policy will be manipulated and altered during the implementation stage and so while the written policy statement is a useful indicator of the broad characteristics of planning programmes, it is the individual planning decision at ground level which will most accurately reflect the success achieved by rural settlement planning in the fulfilment of its objectives. Culpability for the fact that written policy and actual decisions often exhibit signs of generic breakdown may be attributed to the process of policy implementation.

Policy implementation

The implementation of agreed rural settlement policy is the most clouded area of the planning process. Several explanations may be advanced as to why policy and action are often different, and some of these are reproduced in figure 1.2. For example, the inability to translate policy to ground-level decisions may be due to a restricted availability or even absence of particular resources in the right place at the right time. The idea of resources here should be viewed in its widest context so as to include such items as suitable parcels of land, manpower and developers who are sympathetic to planning objectives, as well as the more obvious financial considerations. Further complications arise from the fact that these resources are rarely under the immediate control of the planners themselves, meaning that policy implementation is consequent on the degree of co-operation achieved by planning authorities with other local authority departments (e.g. housing and education), national resource authorities (e.g. water and electricity), national public corporations (such as the Post Office) and the entire gamut of private sector individuals, groups and corporations who are concerned with the provision of life-style requirements in rural areas. Such co-operation is a complex logistic and (more important) political operation, particularly in a rural context where circumstances are continually changing and flexible planning approaches are required to serve these dynamic needs. Thus planners are faced with the difficult duality of requiring both rigid long-term proposals to ensure the concurrence of resource allocation by different organizations, and flexible short-term policies which are able to accommodate the changing nature of the settlements and communities which are to be planned. Policy implementation is easily hindered by this dilemma.

Other factors are also at work in the implementation process. For example, there will be considerable variation in the interpretation of written policy statements according to the motives of the interpreter. The translation of often abstract policy wording into active meaning will be different between planner and politician, economist and conservationist, developer and protester. Any such variation is extenuated in the numerous ‘special cases’ requiring decisions by planners. Certain applications may not conform with established policy but will receive the backing of planning authorities as ‘one-off’ developments in special circumstances. The special case phenomenon can equally be used to prevent the progress of an application which might otherwise have been allowed. Special cases will often form a platform for the exertion of localized political influence in either a negative or positive direction.

The implementation of planning policy should certainly not be symbolized as a tangled web of intrigue and corruption. Indeed, the majority of decisions involving implementation are processed in a straightforward and clearly defined manner. However, rural areas do display evidence of planning action which has deviated from written policy, and whether this is caused by administrative, perceptive or resource factors, it is the end result by which rural settlement planning is judged. Vagaries of implementation clearly shape the end result of planning activity in rural settlements.

What actually happens

The obscurity of how written policy becomes implemented is f...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Guide to reading

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Change in rural settlements

- 3 Theory and rural settlement planning

- 4 Central government legislation and advice

- 5 Development plans and their reviews

- 6 Structure-plan policies

- 7 Establishing a policy framework

- 8 Rural settlement planning in practice

- 9 Policy implementation

- 10 Local planning in rural areas

- 11 Special cases: the role of designated areas

- 12 What future?

- Bibliography

- Author index

- Subject index