![]()

PART I

IN THE EYE OF THE BEHOLDER: IDENTIFYING AND DEFINING LESBIAN BEAUTY NORMS

When thinking of lesbian beauty what comes up for me is the ‘Michigan Women’s Music Festival’ from years ago in the sunlight, naked, beating drums, smiling and dancing. It is the unfolding of the journey in each of us; the journey from oppression. Also, how do I fit? I’m older now, settled 16 years with a partner and overweight–and I feel more beautiful than ever.

–Anonymous workshop participant who was asked “What do you think of when you hear ‘lesbian beauty’?”

![]()

Yeah, You

Carol Wuebker

She has the strength of workers at iron forges in her arms,

she is the water for a thousand parched lawns in Abu Dhabi,

she is the snow banked river in Montana,

she has magellanic clouds in her eyes.

She has the dexterity of a hundred-word-a minute typist in the manual

typewriter typist’s pool.

Her feet have trodden paths

she never knew she would follow, Oregon trails not meant for debutantes.

She has flown above the Kamchatka peninsula and the forty-ninth

parallel, and never been shot down.

She’s crossed the Rubicon in me, she can not go back.

(She’ll never be

some stick figure

in

Elle or

Cosmo or

Vanity Fair.

They are fakes

and

pages are thin.)

But she is my warm,

I know her by her scent and the touch of her skin,

her face is the first thing I seek when I walk in the door,

she is no icon.

She is flesh and beating heart and welcoming arms and sharp, like mind

and hello, how was your day,

and she has a body, and she has a soul, and she has a mind,

and she has my trust, and my comfort,

and my ebb and my flood,

she is my world geography, my world history, my major subject,

the first wonder of the world,

she is my most exotic journey,

and she is my coming back home.

Carol Wuebker is a computer geek living in Sacramento, California. She has a Bachelor of Science in German, which provides no end of amusement to her partner, Marjorie Gelus. They live happily in a little house in the suburbs with three cats.

Address correspondence to: Carol Wuebker, 2232 lone Street, Sacramento, CA 95864.

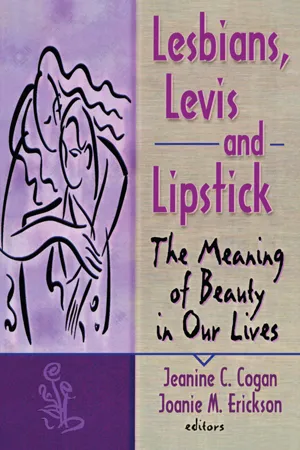

[Haworth co-indexing entry note]: “Yeah, You.” Wuebker, Carol. Co-published simultaneously in

Journal of Lesbian Studies (The Haworth Press, Inc.) Vol. 3, No. 4, 1999, pp. 13-14; and:

Lesbians, Levis and Lipstick: The Meaning of Beauty in Our Lives (ed: Jeanine C. Cogan and Joanie M. Erickson) The Haworth Press, Inc., 1999, pp. 13-14; and:

Lesbians, Levis and Lipstick: The Meaning of Beauty in Our Lives (ed: Jeanine C. Cogan and Joanie M. Erickson) Harrington Park Press, an imprint of The Haworth Press, Inc., 1999, pp. 13-14. Single or multiple copies of this article are available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery Service [1-800-342-9678, 9:00 a.m. - 5:00 p.m. (EST). E-mail address:

[email protected]].

![]()

Beauty Mandates and the Appearance Obsession: Are Lesbian and Bisexual Women Better Off?

Anna Myers

Jennifer Taub

Jessica F. Morris

Esther D. Rothblum

SUMMARY. This article examines the effects of appearance norms within lesbian communities, drawing both on the research literature and on direct interviews with lesbian and bisexual women. In particular, the authors assess the impact of heterosexual beauty mandates on women’s communities and ask whether lesbian and bisexual women are affected by the dominant culture’s beauty mandates to a similar or lesser degree than heterosexual women. In addition, the authors examine appearance mandates developed by women within lesbian subculture. The positive and negative effects of these various “styles” on members of different lesbian subcultures are discussed.

[Article copies available for a fee from The Haworth Document Delivery Service: 1-800-342-9678. E-mail address: [email protected]] “Being female means being told how to look” (Rothblum, 1994, p. 84). For heterosexual women, the beauty standard is unavoidable: the images stare from magazines, billboards, TV screens, department store make-up counters–the list goes on. But what, if anything, does the heterosexual women’s beauty ideal mean for women who are not heterosexual? To date, there has been little examination of the impact of the dominant culture’s beauty standards on lesbian or bisexual communities. Prior to coming out, lesbian and bisexual women likely are pressured to conform to the same appearance norms as heterosexual women. Does coming out subsequently free lesbians and bisexuals from these norms, allowing them to find their own, unique styles? Or, is female beauty socialization carried over into lesbian and bisexual communities? Do these communities impose appearance standards of their own–standards perhaps as restrictive and narrow as heterosexual norms? Drawing on prior research, as well as on interviews with 20 lesbian and bisexual women from across the United States, this article examines ways in which female beauty mandates impact lesbian and bisexual women and raises questions about the relative freedom from such mandates currently experienced by these women in their own communities.

RESEARCH COMPARING LESBIAN AND HETEROSEXUAL WOMEN’S DISSATISFACTION WITH PHYSICAL APPEARANCE

Throughout their lives, all women are socialized to value a certain narrowly defined standard of physical attractiveness. Does this socialization persist after women discover that they are not heterosexual and begin to affiliate with lesbian and bisexual subcultures? We were unable to discover any empirical research to date which has directly addressed this question. Several studies, however, have compared heterosexual and lesbian women with regard to their level of satisfaction with their physical appearance.

Presumably, women are more satisfied with their bodies when their bodies conform to standards of what is generally considered “physically attractive.” It has been hypothesized that the lesbian community protects women from body dissatisfaction because lesbian culture deemphasizes the importance of physical attractiveness (Beren, Hayden, Wilfley, & Grilo, 1996). If lesbians are freed from the tyranny of the heterosexual beauty standard, one would expect them to report more satisfaction with their diverse body types than heterosexual women. Results from studies comparing lesbian and heterosexual women’s level of body dissatisfaction have not supported this hypothesis, however.

For example, Striegel-Moore, Tucker, and Hsu (1990) compared 30 lesbian and 52 heterosexual female undergraduates on measures of body esteem, self-esteem and disordered eating. Their research found no significant differences in body dissatisfaction between the two groups.

A second study by Herzog, Newman, Yeh, and Warshaw (1992) compared 45 lesbian and 64 heterosexual women with regard to body image, weight, eating attitudes and eating behaviors. They found that their sample of lesbians was significantly heavier and more satisfied with their overall appearance than their heterosexual sample. However, they also found that the two groups shared concerns about physical attractiveness and weight, in that both groups reported that they wanted to weigh less and considered thinner women to be more attractive than heavier women.

In a third study, Brand, Rothblum and Solomon (1992) compared levels of body dissatisfaction among 124 lesbians, 133 heterosexual women, 13 gay men, and 39 heterosexual men. The authors found that lesbian and heterosexual women reported significantly more dissatisfaction with their bodies than gay and heterosexual men–a finding which suggests that body dissatisfaction is just as prevalent among lesbians as among heterosexual women. The authors conclude that gender is a stronger predictor of body dissatisfaction than sexual orientation, in that women were more likely than men to be dissatisfied with their bodies–regardless of their sexual orientation.

A final study by Beren and colleagues (1996) compared 58 gay men, 58 heterosexual men, 69 lesbians and 72 heterosexual women on measures of body dissatisfaction. The authors found that again, lesbians and heterosexual women did not differ significantly with regard to body dissatisfaction, but that gay men were more dissatisfied with their appearance than heterosexual men.

While there is some disagreement among the findings of these four studies, overall it appears that lesbians report substantial levels of body dissatisfaction, and that their level of dissatisfaction is similar to the level reported by heterosexual women. While none of these studies included bisexual women, since gender is such an important variable in body image, it is likely that bisexual women are similarly dissatisfied with their bodies. If women’s body dissatisfaction is seen as being the result of female socialization to accept a narrowly defined beauty ideal, it follows that these beauty ideals continue to affect women as they make the transition from heterosexual to lesbian and bisexual communities.

HISTORY OF APPEARANCE NORMS IN LESBIAN COMMUNITIES

An examination of lesbian history shows that lesbian communities have always had norms for physical appearance. Rothblum (1994) notes that, as the dominant culture’s norms for female appearance have changed over time, so have the norms of the lesbian community. An important difference between the two norms, she says, is that while the dominant culture’s norms have to do primarily with how women can attract men, lesbian norms have served a dual purpose: to allow lesbians to identify each other, and to provide a group identity that is distinct from that of women in the dominant culture.

In a review of U.S. lesbian history and culture in the 20th century, Faderman (1991) found appearance to be an important part of lesbian life. She notes that in the 1920s, being lesbian became chic among bohemian women. Black and white lesbians in Harlem and Greenwich Village began to form distinct subcultures, for which appearance lent a sense of group identity. Later, during World War II, women began to take factory jobs where they had to wear pants. This provided the opportunity for lesbians who hated dresses to continue to wear pants after the war, with less need to fear negative reactions.

By the 1950s, the butch/femme style emerged in lesbian communities. Although butch/femme culture encompassed far more than just a dress code, appearance was nevertheless a significant feature. Butch lesbians typically had short haircuts and wore man-tailored clothing, whereas femme lesbians tended to dress and groom themselves in a manner considered “feminine” for the time period. Butch/femme styles allowed lesbians to identify one another, as well as affording lesbians a way of expressing themselves as separate from the dominant culture. Among poor and working-class lesbians, butch/femme identity became a rigidly enforced code. Lesbians who were not clearly butch or femme were termed kiki and were unwelcome in places lesbians gathered. At least part of this rigidity had to do with fear. If a woman in a bar was not clearly butch or femme, other lesbians would be afraid to approach her lest she turned out to be a policewoman who did not “know how to dress.”

In refusing to be invisible to the dominant culture, working-class and poor butch/femme lesbians paid the price for their “free” expression during all-too-common police raids and beatings. In contrast, middle-class and wealthy lesbians of the 1950s usually avoided butch/femme styles and were more likely to pass as heterosexual. Faderman (1991) quotes the Daughters of Bilitis’ newsletter, which urged its middle-class readership to adopt “a mode of behavior and dress acceptable to society” (p. 180).

While the appearance norms of the dominant culture changed radically during the 1960s, Faderman reports that lesbian norms remained fairly constant until the dawning of the feminist movement in the 1970s. At this time, androgyny replaced butch/femme as the accepted appearance style. By dressing in an androgynous manner, women sought to distance themselves from the notion that [heterosexual] women should be a “decoration” for men. Women in lesbian communities were encouraged to dress for comfort and utility rather than to enhance their physical appearance in a style pleasing to heterosexual men. In rejecting the butch/femme aesthetic, lesbians of this time period also rejected the duality inherent in butch/femme roles: the mandate that one partner should be “masculine” and the other “feminine.” This mandate began to be seen as patriarchal and oppressive. Lesbians of this time period sought to create more freedom for women to be themselves rather than to fit into a particular mold.

Loulan (1990) argues that, rather than creating more flexible appearance norms, lesbians of this time period simply created another oppressive norm. During the 1970s feminist movement, flannel shirts, blue jeans, work boots, an absence of jewelry or makeup, and short hair became de rigueur. Among lesbians, this norm was as rigidly enforced as the butch/femme code had been enforced in the years prior. Loulan describes how butch/femme lesbians of this time period were ostracized for aping heterosexual styles, and how this attitude persists in lesbian communities today.

According to Rothblum (1994), the 1980s and 1990s have reflected greater diversity in the lesbian community. She points out that in the last 20 years, lesbians of a variety of ethnicities and cultures have become more visible to the dominant culture, often forming communities of their own. Additionally, butch/femme styles have undergone a renaissance. The sadomasochist (S/M) subculture, which has its own style of dress and behavior, has become more visible. In the last 20 years, then, it is possible that lesbian and bisexual women have begun to be less rigid in the extent to which they hold one another to standards of “appropriate” appearance and behavior.

The authors cited above describe several ways that appearance standards do exist within lesbian communities.1 Historical analyses suggest that lesbians have always paid attention to physical appearance in order to feel attractive and also to identify one another and/or to make a political statement. However, the question still remains whether female socialization to value certain standards of appearance persists after women come out.

DO APPEARANCE NORMS PERSIST AFTER WOMEN COME OUT?

In attempting to examine the question about the durability of the heterosexual beauty standard in women’s communities, we interviewed 18 lesbian and 2 bisexual women about their experience of appearance norms in lesbian communities. Specifically, we asked whether they believed that their communities held women to certain appearance standards, and if so, whether those appearance standards were any more or less restrictive than heterosexual appearance norms. Our interviews took place in person, by telephone, and over electronic mail. Our respondents were 20 women whose ages ranged from 17 to 60 years old (Mean = 32). Of those women who shared their racial or ethnic heritage, 12 identified as white, 1 as Latina, and 1 as mixed-race.

Because our sample size is small, no definitive conclusions about appearance norms in lesbian communities can be drawn from these interviews; however, they may uncover themes worthy of further investigation. Additionally, it is not possible to generalize from the experience of these women to all lesbian and bisexual women. However, our respondents were able to tell us what they experienced to be the norms regarding physical appearance within their local lesbian communities.

To so...