![]()

J. Mark G. Williams and Jon Kabat-Zinn

The editors introduce this book on Mindfulness, explaining its rationale, aims, and intentions. Integrating mindfulness-based approaches into medicine, psychology, neuroscience, healthcare, education, business leadership, and other major societal institutions has become a burgeoning field. The very rapidity of such growth of interest in mainstream contemporary applications of ancient meditative practices traditionally associated with specific cultural and philosophical perspectives and purposes, raises concerns about whether the very essence of such practices and perspectives might be unwittingly denatured out of ignorance and/or misapprehended and potentially exploited in inappropriate and ultimately unwise ways. The authors suggest that this is a point in the development of this new field, which is emerging from a confluence of two powerful and potentially synergistic epistemologies, where it may be particularly fruitful to pause and take stock. The contributors to this book, all experts in the fields of Buddhist scholarship, scientific research, or the implementation of mindfulness in healthcare or educational settings, have risen to the challenge of identifying the most salient areas for potential synergy and for potential disjunction. Our hope is that out of these interchanges and reflections and collective conversations may come new understandings and emergences that will provide both direction and benefit to this promising field.

We are delighted to introduce this book that first appeared as a special issue of the international journal Contemporary Buddhism. The book is devoted exclusively to invited contributions from Buddhist teachers and contemplative scholars, together with mindfulness-based professionals on both the clinical and research sides, writing on the broad topic of mindfulness and the various issues that arise from its increasing popularity and integration into the mainstream of medicine, education, psychology and the wider society. That two scientist/clinicians, neither of whom identifies himself as a Buddhist, and neither of whom is a Buddhist scholar, were invited to be guest editors, is itself an event worthy of note, and a sign of the good will and spaciousness of view of the journal's outgoing editor, John Peacocke. We thank him for the profound opportunity, and the faith he has placed in us.

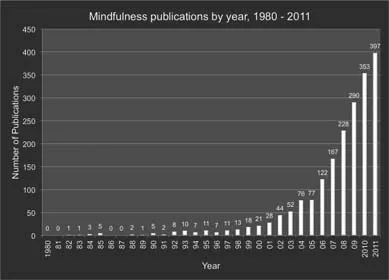

For many years, from the early 1980s until the late 1990s, the field we might call mindfulness-based applications went along at a very modest level, at first under the aegis of behavioural medicine. The number of papers per year coming out followed a linear trajectory with a very low slope. Someplace in the late 1990s, the rise began to go exponential, and that exponential rate continues (Figure 1). Interest and activity is no longer limited to the discipline of behavioural medicine, or mind/body medicine, or even medicine. Major developments are now occurring in clinical and health psychology, cognitive therapy, and neuroscience, and increasingly, there is growing interest, although presently at a lower level, in primary and secondary education, higher education, the law, business, and leadership. Indeed, in the UK, the National Health Service (NHS) has mandated mindfulness-based cognitive therapy as the treatment of choice for specific patient populations suf-

FIGURE 1

Results obtained from a search of the term ‘mindfulness’ in the abstracts and keywords of the ISI web of knowledge database on March 19, 2012. The search was limited to publications with English language abstracts. Figure prepared by David Black, MPH, Ph.D., Cousins Center for Psychoneuroimmunology, Semel Institute for Neuroscience & Human Behavior, University of California, Los Angeles.

fering from major depressive disorder. What is more, at a scientific meeting on mindfulness research within neuroscience and clinical medicine and psychology in Madison in October 2010,1 delegates from the National Institute of Health reported that NIH alone funded more than 150 research projects in mindfulness over the preceding five years. The growth of interest in mindfulness in the past 10 years has been huge, and in many ways extraordinary.

From the perspective of 1979, when mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) came into being in the Stress Reduction Clinic at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center in Worcester, Massachusetts, the idea that mindfulness meditation would become integrated into mainstream medicine and science to the extent that it already has, that the NIH would fund mindfulness research at the levels that it has, as well as hold a day long symposium on its campus in May of 2004 entitled Mindfulness Meditation and Health, and that the NHS in the UK would mandate a therapy based on mindfulness nationwide, is nothing short of astonishing. This interest is not confined to North America and the UK. It is occurring worldwide.

Indeed, given the zeitgeist of the late 1970s, the probability that Buddhist meditation practices and perspectives would become integrated into the main-stream of science and medicine and the wider society to the extent that they already have at this juncture, and in so many different ways that are now perceived as potentially useful and important to investigate, seemed at the time to be somewhat lower than the likelihood that the cosmic expansion of the universe should all of a sudden come to a halt and begin falling back in on itself in a reverse big-bang … in other words, infinitesimal. And yet, improbable as it may have been, it has already happened, and the unfolding of this phenomenon continues on many different fronts. In the large, it signals the convergence of two different epistemologies and cultures, namely that of science and that of the contemplative disciplines, and in particular meditation, and even more specifically, Buddhist forms of meditation and the framework associated with their deployment and practice. Since Buddhist meditative practices are concerned with embodied awareness and the cultivation of clarity, emotional balance (equanimity) and compassion, and since all of these capacities can be refined and developed via the honing and intentional deployment of attention, the roots of Buddhist meditation practices are de facto universal. Thus, as Kabat-Zinn argues in the closing contribution, it is therefore appropriate to introduce them into mainstream secular settings in the service of helping to reduce suffering and the attendant mind-states and behaviours that compound it, and to do so in ways that neither disregard nor disrespect the highly sophisticated and beautiful epistemological framework within which it is nested, but on the contrary make profound use of that framework in non-parochial ways consistent with its essence.

The emergence within science and medicine of interest in Buddhist meditative practices and their potential applications represents a convergence of two different ways of knowing, that of western empirical science, and that of the empiricism of the meditative or consciousness disciplines and their attendant frameworks, developed over millennia. The world can only benefit from such a convergence and intermixing of streams, as long as the highest standards of rigor and empiricism native to each stream are respected and followed. The promise of deepened insights and novel approaches to theoretical and practical issues is great when different lenses can be held up to old and intractable issues.

At the same time, such a confluence of streams and the sudden rise in interest and enthusiasm carries with it a range of possible problems, some of which might actually seriously undermine and impede the deepest and most creative potential of this emergent field and hamper its fullest development. It is in this context that we hope this special issue will spark ongoing dialogue and conversation across disciplines that usually do not communicate with each other, and equally, will spark an introspective inquiry among all concerned regarding the interface between what has come to be called ‘first person experience’ and the ‘third person’ perspective of scientists studying aspects of human experience from a more traditional vantage point (Varela and Shear 1999). The promise of the convergence and cross-fertilization of these two ways of understanding the world and human experience is large. It is presently becoming a leading current of thought and investigation in cognitive science (Varela, Thompson and Roach 1991; Thompson 2007) and affective neuroscience (Lutz, Dunne and Davidson 2007). In a parallel and overlapping emergence dating back to 1987, the Mind and Life Institute has been conducting dialogues between the Dalai Lama and scientists and clinicians, along with Buddhist scholars and philosophers on a range of topics related to the confluence of these streams (see Kabat-Zinn and Davidson 2011; www.mindandlife.org).

If increasing interest and popularity in regard to mindfulness and its expressions in professional disciplines might inevitably bring a unique set of challenges and even potential problems—the stress of ‘success,’ so to speak—then questions to ponder at this juncture might be: Are there intrinsic dangers that need to be kept in mind? Is there the potential for something priceless to be lost through secular applications of aspects of a larger culture which has a long and venerable, dare we say sacred tradition of its own? What are the potential negative effects of the confluence of these different epistemologies at this point in time? Do we need to be concerned that young professionals might be increasingly drawn to mind-fulness (or expected by their senior colleagues to use or study a mindfulness-based intervention) because it may be perceived as a fashionable field in which to work rather than from a motivation more associated with its intrinsic essence and transformative potential? Can it be exploited or misappropriated in ways that might lead to harm of some kind, either by omission or commission? Might there even be elements of bereavement and loss on the part of some, mixed in with the exhilaration of any apparent ‘success’, as often happens when success comes rapidly and unexpectedly?

If we can ask such sometimes hard or even uncomfortable questions, and if we can discern elements of both possible danger and promise that we have not thought of before, and if we can stay in conversation and perhaps collaboration across domains where traditionally there has been little or no discourse, perhaps this confluence of streams will give rise to its maximal promise while remaining mindful of the potential dangers associated with ignoring the existence of or disregarding some of the profound concerns and perspectives expressed by the contributors to this special issue. The very fact that a scholarly journal devoted to Buddhism would host this kind of cross disciplinary conversation is itself diagnostic of the dissolving of barriers between, until recently, very separate areas of scholarship and inquiry.

This book thus offers a unique opportunity for all involved in this field, as well as those coming to it for the first time, to step back at this critical moment in history and reflect on how this intersection of classical Buddhist teachings and Western culture is faring, and how it might be brought to the next level of flourishing while engendering the least harm and the greatest potential benefit.

Our first task as Editors was to draw together an international team to contribute original essays, including authors who might raise issues of which some of us may not even be aware either from the scholarly or cultural perspective, issues that might shed some light on how this field could be enriched and deepened. To that end, we invited scholars of Buddhism, scientists, clinicians and teachers who we thought would be able to speak deeply to two audiences: first, to those in the Buddhist community who may not be so familiar with the current use and growing influence of mindfulness in professional settings, or who may be a little puzzled or anxious about it; second, to teachers and researchers within the Western medical, scientific, psychotherapeutic, educational or corporate settings, who would like to be more informed about current areas of debate within Buddhist scholarship.

With this aim in mind, we have organized the essays in a certain sequence, starting from scholars of Buddhism who can help us situate the contemporary debate in an historical context, then moving to teachers and clinicians/scientists for their perspective, before finally coming back to the historical context and the question of how best to honour the traditions out of which the most refined articulation of mindfulness and its potential value arose, yet at the same time, making it accessible to those who would not seek it out within a Buddhist context.

From Abhidharma to psychological science

In the first essay, Bhikkhu Bodhi examines the etymology and use of the term sati in the foundational texts to help convey the breadth and depth of mindfulness. He explores the differences in treatment of sati pointing out how those systems that give greater emphasis to mindfulness as remembrance require re-interpretation in the light of those that place greater emphasis on what he calls ‘lucid awareness.’ He examines passages from Nyanaponika Thera to show the dangers of using ‘bare attention’ as an adequate account of sati. Against this background, his article focuses on both the beauty and the challenges inherent in bringing mind-fulness into modern healthcare, education and neuroscience. His article lays important groundwork for understanding the meaning and use of words relating to mindfulness in the texts, and offers a unique perspective on what is and is not important in bringing such practices to the West.

Georges Dreyfus' essay explores the potential hazards of an incomplete understanding of mindfulness, both from the theoretical perspective but also, of major concern, on the experiential level as well. In particular, he argues that current definitions of mindfulness that emphasize only one of the themes present in the historical traditions—present-centred non-judgmental awareness—may miss some of the central features of mindfulness. He explores the implications for current practice of taking fuller account of those Buddhist texts that present mind-fulness as being relevant to the past as well as the present, including a capacity for sustained attention that can hold its object whether the ‘object’ is present or not.

Andrew Olendzki continues this examination of the same issues using first the Abhidharma system as found in the Pali work Abhidhammatthasangaha in which mindfulness is seen as an advanced state of constructed experience, and wisdom as arising only under special conditions; contrasting it with the Sanskrit Abhidhar-makosa, where both mindfulness and wisdom are counted among the ‘universal’ factors, and thus ‘arise and pass away in every single mind moment.’ This has important implications for what we understand about what we are doing in meditation, for the latter approach assumes that, although mindfulness and wisdom are hidden most of the time by attachment, aversion and delusion, the mind is fundamentally already awakened and inherently wise. As Olendzki says ‘The practice becomes one of uncovering the originally pure nature of mind.’ He suggests that it is the latter approach that provides a basis for an Innateist model of development, and he critiques this model from a constructivist perspective.

What is the contemporary teacher of a mindfulness-based intervention to make of this debate? What are its implications?

John Dunne's article speaks directly to this issue. He focuses on ‘non-dual’ practice in relation to the more mainstream descriptions found in Abhidharma literature, examining Buddhist non-dualism, including attitudes to and theories about thoughts and judgments and how these arise and are affected by practice. He takes up the arguments made in Georges Dreyfus' article, pointing out how Dreyfus's analysis, though an excellent presentation of a ‘classical’ Abhidharma approach to mindfulness, may not be a good fit for the non-dual Innateist approaches to mindfulness that are the more immediate forebears of the mind-fulness practiced by clinicians and studied by many scientists in the West, as discussed by Jon Kabat-Zinn in his description of the range of Buddhist influences on the development of MBSR.

John Teasdale and Michael Chaskelson have contributed two essays that take up the challenge of bringing together Buddhist theory and clinical practice. The first article offers a way of looking at the first and second of the Four Noble Truths from the perspective of the question: ‘what has this to do with those who come to an MBSR or MBCT class?’ After all, they say, participants in classes are primarily looking for relief from the stress and exhaustion of their illness, or they want to stay well after depression. They do not come asking for resolution of existential suffering.

The authors take this question head on: How are the Four Noble Truths relevant to clinician's concerns? Their article emphasizes the way in which our minds are constructed in a way that makes it very difficult to see clearly the nature of our own suffering, and how we add to it by the way we react to moment by moment experience. They also show the compulsive quality to our attachments, expressed in the very language of ‘shoulds’ and ‘musts’ and ‘if onlys’—how absorbed we are in wishing things were different from how we find them. In so doing, the authors give a deeper meaning to the notion of a ‘cognitive’ therapy, beyond the cartoon images that are so often mistaken for real knowledge and understanding of the approach. Not only this, but their analysis reminds us how much emotional pain in the Western world arises from the same conditions that have always operated, and how, as the authors express it ‘the patterns of mind that keep people trapped ...