- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Overhead Costs

About this book

Professor Lewis is to be congratulated upon being among the first economists to tackle the tricky subject of controlling the nationalised industries."Financial Times

This book analyses some of the difficulties of costing and price formation that arise out of the existence of overhead costs in nationalised industry. Issues such as the law relating to monopoly and the accountability of public enterprise are considered, along with complex questions such as price formation and the problem of policy in public corporations.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter V

Competition in Retail Trade

“The prejudices of some political writers against shopkeepers and tradesmen are altogether without foundation. So far from it being necessary either to tax them or to reduce their number, they can never be multiplied so as to hurt the public though they may be so as to hurt one another. The quantity of grocery goods, for example, which can be sold in a particular town, is limited by the demand of that town and its neighbourhood. The capital, therefore, which can be employed in the grocery trade, cannot exceed what is sufficient to purchase that quantity. If this capital is divided between two different grocers, their competition will tend to make both of them sell cheaper than if it was in the hands of one only; and if it were divided among twenty, their competition would be just so much the greater and the chance of their combining together, in order to raise the price, just so much the less. Their competition might, perhaps, ruin some of themselves; but to take care of this is the business of the parties concerned, and may be safely left to their own discretion.”

Thus spake the old master in 1776.1 His conclusion has never been widely accepted. Retailers have always claimed that competition hurts the public no less than themselves and sought public support for their elaborate efforts to restrain it. Even the classical writers were unsure.2 Modern economists feel more confident to tackle the problem, using as tools the newly shaped theory of monopolistic competition, but a combined knowledge of theory and of the structure of retailing is all too rare, and attempts at a synthesis all too infrequent. A further venture does not therefore seem superfluous. Neither is the moment untimely. In November 1941 the Board of Trade made an Order prohibiting any person from opening a new retail business in this country except under licence. This was purely a wartime measure, and the President of the Board pledged himself to withdraw it after the war. But its enactment raised some hopes that permanent restrictions would follow, and recent fortunes at the polls have helped to revive these hopes. Meanwhile, some town planning authorities are already using, or planning to use, their powers in such a way as drastically to reduce the number of shops. This article may, perhaps, help to clarify the issues involved.

The procedure adopted is to analyse first the effects of competition in prices and in services. The third section deals with certain special forms of competition which have been denounced as unfair, and the fourth section tries to reach conclusions on the main issues in the debate.

I

The Number, Size and Location of Shops

1. In the contemporary approach, the earliest doubts of the effectiveness of competition in retailing are associated with the name of Hotelling. In a stimulating article3 he argued, on certain special assumptions, that the effect of competition would be to cause sellers to cluster together, instead of dispersing at equal distances, and showed that this undesirable result in location causes transport costs to be excessive. Various writers interested themselves in the problem, but the outstanding advance is the contribution of Lerner and Singer eight years later, in an article4 which generalises Hotelling’s case, and is the most convenient starting point.

The basic assumption is that the customers are strung out at equal distances along a road. Then, on the further asumptions (a) that no two shops can be on the same spot; (b) that each end of the road is a cul-de-sac; (c) that each customer pays his own transport costs; (d) that the number of shops is given; (e) that the price is fixed; and (f) that there are no economies of scale, Lerner and Singer show that in equilibrium (i) there cannot be more than two shops together, and (ii) there must be two shops together at each end of the road. They also imply that each shop must have the same number of customers, unless there is an odd number of shops, when one may have more than the others; but this is not so. The third condition of equilibrium is only that no shop may have less customers than half the number between any two other shops, or less than the shops at the end. Shops may be equidistant, but need not be, and as in any case the end shops must be paired, transport costs must be above the ideal.

Removing some of these assumptions brings the equilibrium conditions nearer to the ideal. Assumption (a) makes a negligible difference. Removing assumption (b) destroys conclusion (II); if the road connects say two big market centres, the first shop at either end of the road may stand alone. As for assumption (c), Lerner and Singer themselves reach the important conclusion that if transport costs are paid not by the customers but by the sellers, shops will be located at equal distances from each other, which is the ideal situation.

2. To advance the analysis beyond the Lerner-Singer stage it is necessary to remove the remaining assumptions. If the number of shops is not given, and prices are not fixed, and there are no economies of scale, the number of shops will be as great as the number of customers. This odd conclusion brings into the open the odd assumption underlying the whole analysis that transport cost from wholesaler to retailer can be neglected, but not transport cost from retailer to customer, an assumption which becomes the more unreasonable the greater the ratio of shops to customers. Nevertheless, the conclusion serves to remind us that the convenience of customers requires that there should be as many shops as possible, each small, and that it is only economies of scale which prevent this. The assumption of constant costs is incompatible with equilibrium in retailing, given dispersal of customers. For if a reduction in the size of shops will not increase costs, it will pay some seller to insert himself between two existing shops.

Should shops, then, be of “optimum” size, meaning the minimum size consistent with minimum average cost, or should they be smaller, and if so, how much smaller? If we can assume that the inconvenience of not having a shop nearby can be translated into monetary terms as a function of the distance of the shop, the problem is capable of precise solution.

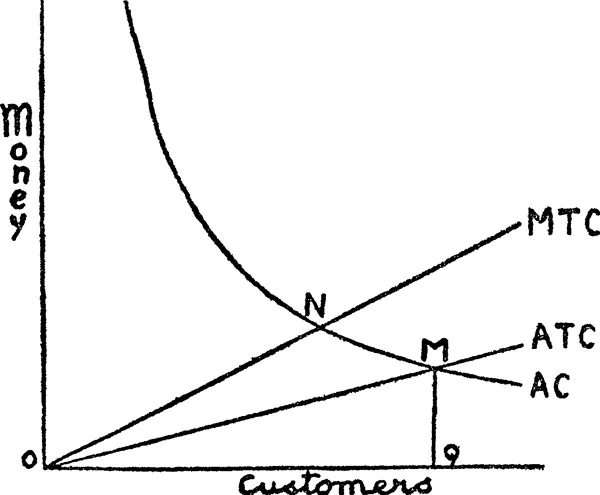

Let us assume (I) that all shops have the same costs; (2) that there are no prime costs, but only an overhead, so that the average cost curve is a rectangular hyperbola (marginal costs are assumed away only for convenience of exposition; what matters is the assumption of falling average cost); (3) that the customers are strung out along a road on either side of each shop, one customer for each unit of distance; (4) that each customer buys one unit (money value) of merchandise; and (5) that the inconvenience of distance can be expressed as one unit of money per unit of distance, paid by the customer. Then the following diagram shows the position.

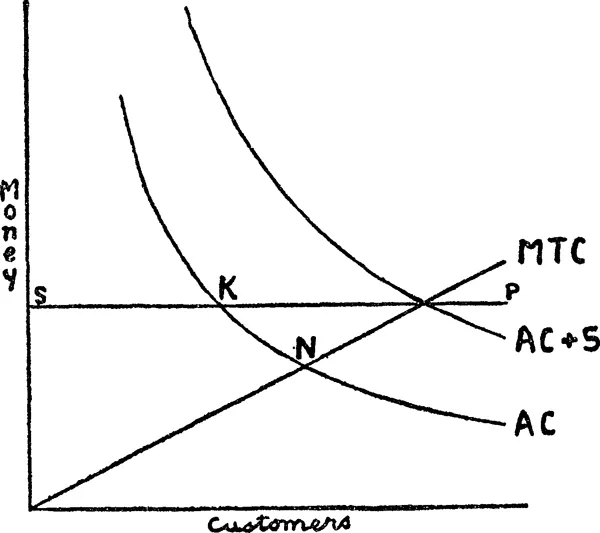

AC is a rectangular hyperbola, representing the average cost curve of any shop, varying with the number of its customers (and therefore sales). MTC is the curve of marginal transport costs; the first two customers, one on either side, incur one unit each, the next two customers incur two units each, and so on; the curve can thus be drawn for simplicity as a straight line with a slope of 0.5. Total transport cost is the area lying beneath it, and average transport cost per customer will be a line with a slope of 0.25.

The ideal number of shops (or number of customers per shop) is such that, given the total number of customers to be served, the sum of shop costs and transport costs is at its minimum. This condition is fulfilled when for each shop the sum of average shop costs and average transport costs is minimised. Since for each new customer the former falls and the latter rises, the condition is fulfilled when the negative slope of AC equals the positive slope of ATC. AC being a rectangular hyperbola and ATC a straight line from the origin, this will be at the point where they meet. M gives us the ideal size of shop. It cannot correspond with the point where average shop cost would be minimised; since ATC is rising and AC is falling, the minimum point of ATC+AC must be to the left of the minimum point of AC. In other words, it is desirable that shops should be of less than “optimum” size.

Will competition bring about the right size? If there is free entry, and if there cannot be abnormal profits, the price charged by each shop (its gross margin) must lie somewhere along AC. If a shop reduces its price by one unit it will attract two customers, one on either side, who transfer their custom from its rivals. It pays therefore to lower the price by one unit if getting two more customers will reduce AC by more than one unit. Its equilibrium is therefore at the point N where the slope of MTC equals the slope of AC.5 Thus shops will not cut their prices low enough to bring the right size. In competition, there will be too many shops, each too small.

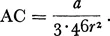

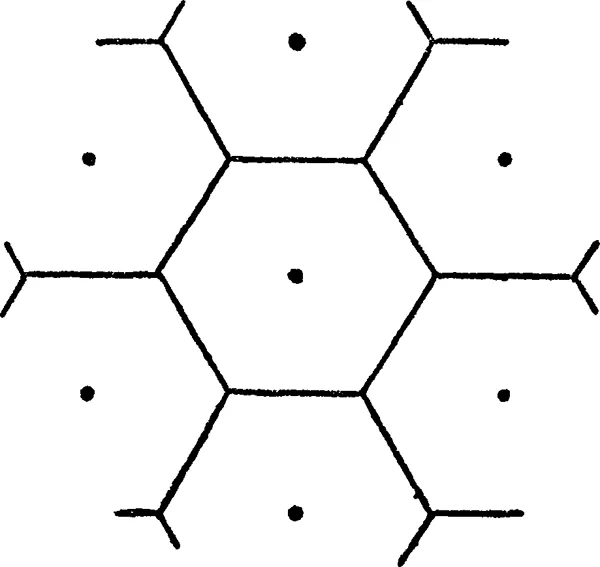

The result can be generalised by assuming that consumers do not live along a road, but are distributed over an area, one in each unit of space. It remains desirable that shops should be equidistant, and this condition can only be fulfilled if each is at the centre of a hexagon. How many shops there should be, and what should be the size of each, is then determined if we know how large the hexagon should be. Retaining our previous assumptions, the solution is as follows : If we write r for the length of the radius of the inscribed circle, the length of each side will be 1.15r. The number of customers equals the area of the hexagon, 3.46r2. Writing a for the overhead costs of each shop, average cost per customer,

To calculate transport costs we first divide the hexagon into its twelve right-angled triangles. In each, taking the customers living along the base, the nearest lives at distance r and the furthest at distance 1.15r. The sum6 of the distances for the base customers is o.61r2, and the total transport cost for the hexagon is twelve times the integral of this, i.e. 2.41r3. This divided by the number of customers gives average transport cost per customer,

The ideal number of shops is given by the condition that the slopes of AC and ATC must be the same. Differentiating gives

Now, in competition a shop will cut its price by one unit so long as the resulting increase of customers reduces AC by more than one unit. Equilibrium therefore results when

This analysis brings out the relevant points. The number of shops depends on the extent of the economies of scale, the density of population (determining the number of customers per unit of distance), and the inconvenience or cost of distant shopping. The greater the economies of scale, and the less the cost of transport, the fewer shops there will and should be. The denser the population, the larger shops will be, and this is worth noting since many people believe that the decentralisation of urban populations which has occurred since 1920 is one of the principal factors explaining the increase in the numbers engaged in distribution in this country.7 In any case, given the dispersion of customers, the ideal size of shop is less than the “optimum”; and, given competition, the actual size will be less than the ideal.8

3. Several qualifications are needed before we can derive from this anything like a complete picture.

First, the analysis has so far assumed that there is price competition, and that each shop cuts prices without taking the reaction of its competitors into account. This does not require that the price of every one of the hundreds of commodities it sells should be keenly competitive; it is enough that average gross margins for any class of trade must be adjusted to the level set by competition, and if this is so, the effect on size is the same. But even this is not a complete picture. To begin with, retail prices in certain trades—cigarettes, patent medicines, some groceries, milk, coal, confectionery, books, periodicals, stationery, lamps, cycles, petrol, motors and motor accessories—are maintained by elaborate arrangements between manufacturers, wholesalers and retailers, which impose heavy penalties for price cutting. The assumption that retailers are free to compete in prices, however, holds good in other trades—some groceries, fish, meat, fruit and vegetables, flowers, furniture, most hardware, drapery, footwear, clothes, pottery and others—and to these the analysis applies, subject to further qualifications.

When prices are fixed the number of shops is a direct function of the level at which they are fixed. In terms of Fig. III (which is constructed on the same cost assumptions as Fig. I), equilibrium is given by the point K at which the horizontal price line SP cuts AC. So long as shops are larger than this they will be making profits; new entrants will then be attracted, reducing the share of each in the trade, until abnormal profits vanish. As the price is usually too high under these schemes (for reasons we shall examine later) the number of shops will be excessive. At this point, however, it will pay any one shop to compete by offering better service. If all shops do this, as they must in competition, all make losses unless their number contracts, and in competition it will contract up to the point where a curve showing the effect on sales of increased expenditure on service has the same slope as the new cost curve (including the additional services). In Fig. III we assume that the cost of the extra services is added not to marginal cost but to overheads; and we also assume that to increase the quality of the service at a cost of xd. per unit of sales has the same effect in stimulating sales as would reducing the price by xd. per unit while keeping the service unchanged. Competitive equilibrium is then given by the intersection of MTC and the fixed price line, to which the number of shops (and AC + S) adjusts itself. Where the extra services take the form of an addition to overhead costs, shops will be larger than they would be if there were competition in price but not in service, but prices will be higher. If they take the form of an addition to marginal costs, shops may be larger or smaller, higher or rising marginal costs making for smaller shops.

Shops may, of course, compete neither in prices nor in service, even though prices are not maintained. If each shopkeeper takes into account the fact that if he cuts prices or offers more service his rivals will follow, shops will be still smaller and more numerous.

The limit to their smallness will be set by the elasticity of demand in the market as a whole, i.e. by Q in Chamberlin’s Fig. 159; in our diagram where elasticity is assumed to be zero it would be one shop for each customer. It is most unlikely in practice that this movement towards the upper limit will get very far. It is certainly unlikely in the United States of America, where aggressive competition is the rule, with chains, super-markets and independents at each other’s throats. Competition is not so keen in this country, but competition between the co-operatives, the multiples and the independents is nevertheless keen enough in non-price-maintained trades to keep the size of shops near to N. In the price-maintained trades price competition is ruled out; service competition tends to check the decrease in shop size, but it is not always very strong and, given the fall in wholesale prices which had been occurring steadily after 1920, it was possible for more and more redundant shops to establish themselves on an ever-widening gross margin.

4. The second qualification concerns transport costs. The conclusion that in competition there must be too many shops depends on the assumption that customers pay transport costs. If the shop pays transport costs, it will take on an extra customer so long as the price exceeds the cost of transporting to him (marginal selling cost being on our assumptions zero). But since (Fig. I) MTC equals the price (AC + ATC) at the point where AC + ATC is at its minimum, it follows that the point ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- I. Fixed Costs

- II. The Two-Part Tariff

- III. The Economics of Loyalty

- IV. The Inter-relations of Shipping Freights

- V. Competition in Retail Trade

- VI. Monopoly and the Law

- VII. The Administration of Socialist Enterprises

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Overhead Costs by W. Arthur Lewis in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.