- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Further Aspects of Piaget's Work

About this book

This book was first published in 1967. This volume presents two areas of Piaget's work on the child's conception of Geometry and then also to Space which were initially published in 1948. It acts as an introduction to Piaget's work in the hope of rousing the interest of teachers with the aim of helping children to learn mathematics by helping them to understand how children form mathematical ideas.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Further Aspects of Piaget's Work by G. E. T. Holloway in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychologie & Psychologie du développement. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

An Introduction to The Child’s Conception of Space

An Introduction to The Child’s Conception of Space

Principal Lecturer in Education

Sidney Webb College of Education

Sidney Webb College of Education

First published 1967

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park,

Abingdon, Oxon, 0X14 4RN

270 Madison Ave, New York NY 10016

by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park,

Abingdon, Oxon, 0X14 4RN

270 Madison Ave, New York NY 10016

© 1960 Routledge

© 1967 National Froebel Foundation

© 1967 National Froebel Foundation

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher, except for the quotation of brief passages in criticism

Introduction*

Piaget’s two books La Representation de I’espace chez l’Venfant and La Geometrie spontanee de Venfant were published in 1948. The English translations appeared in 1956 and 1960 respectively, each consisting of between four and five hundred pages of highly concentrated and complex material. In producing these handbooks we hope to arouse the interest of many more teachers in the work of Piaget and to share with them our deep conviction of the importance of his work for all concerned with the education of children.

The Child’s Conception of Space deals with the following topics:

Topological Space

Projective Space

The Transition from Projective to Euclidean Space

Projective Space

The Transition from Projective to Euclidean Space

In all of these we are brought face to face with aspects of space relations which adults find it hard to see as problematic, but which for children are the main stumbling blocks to spatial understanding.

The majority of teachers are now familiar with the problems which children face in developing the concept of number. That children have to discover the principles of conservation, seriation, permanence of correspondence, reversibility etc., has been revealed to us by Piaget in his book The Child’s Conception of Number and a great deal of related literature. We now look at children in a new light and it is our hope that these handbooks will serve to illuminate a little more of the area of the development of mathematical understanding in children.

Our aim in helping children to learn mathematics must surely be to stimulate the growth process of mathematical ideas. In order to achieve this we need to know and understand the stages of growth of such ideas and to provide experiences appropriate to each of these stages as well as to offer helpful natural bridges towards the next one.

In order to enable a baby to learn to walk we first let it lie on its back and kick its legs in the air, an activity bearing very little resemblance to the ultimate attainment. This is an extreme case, but we could usefully remind ourselves of it from time to time in connection with much of Piaget’s work. In providing mathematical education for our children we hope that they will eventually develop the ability to use a series of codes in order to compare, reason and predict. The practical activity involving material objects in concrete situations which Piaget’s findings indicate as necessary for such a long period of time appears, at first sight, to bear about the same relation to the more developed forms of mathematical thinking as does kicking the legs in the air to walking along the ground. More and more teachers are coming to see that both of these preliminary activities are equally important, and just as any attempt to encourage a baby to walk before it has reached the necessary stage of development is doomed to failure, so also any system of mathematical information imparted to children without their having had adequate experience of the right kind actually impoverishes their development, though it may at first give it a spurious maturity.

Children must assimilate more and more experience in order to be able to make valid generalizations later. How very much later it is not easy for us to appreciate. Piaget helps us to see how long a process is the development of mathematical ideas and how very much it depends on the opportunity to manipulate material. But of course if they have the benefit of ample experiences which will help them on to the right generalizations and mathematical ideas, they may be able to develop much more happily as well as more rapidly than Piaget’s Genevese children who, like many of ours, are taught sums’ and ununderstood ways of getting ‘correct’ results, instead of understanding.

We know that we think because we speak. It is not so often remembered that we speak because we can use our hands. We are increasingly accustomed to the idea of encouraging children to speak in school and long past the state of affairs described by an infant on his return from school, who said ‘I can’t read and I can’t write and she won’t let me talk.’ But perhaps we need more fully to realize the continuing value throughout the primary school of manipulative experience and practical problem-solving arising naturally from situations in which children’s interest has become actively engaged.

In his introduction to The Growth of Understanding in The Young Child Nathan Isaacs quotes my initial response to Piaget’s book The Child’s Conception of Number which was to describe it as being at first incomprehensible and later incredible. It is because of my feeling that the reaction of many teachers to Piaget’s work is similar that I have responded to Mr. Isaacs’s encouragement to embark on this present venture in the hope that it may lead many teachers to look more closely at Piaget’s books and to find in them much that will influence their observation of and approach to children.

I have not attempted to do more than present a brief simplified account of the contents of Piaget’s books, much of the account being in the form of direct quotation. Inevitably, a great deal has been omitted and in particular almost all of the intensely interesting living material of children’s own responses, and the concrete discussions to which these led. This introduction is meant to do no more than ‘break the ice by providing a broad map of Piaget’s own main lines of approach and of the ground he thus covers. If this results in a more widespread study of the original its purpose will have been achieved.

I am greatly indebted to Mr. Isaacs,* who is entirely responsible for obtaining permission for this work to be undertaken, and who has greatly assisted me in planning the presentation as well as having given invaluable help with the selection of the material. I am also very much indebted to Messrs. Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, and to Humanities Press, New York, for giving their permission.

Notes

* This introduction is reproduced from the companion handbook An Introduction to ‘The Child’s Conception of Geometry’ for the greater convenience of readers.

* It is with much regret that I record the death of Nathan Isaacs between the time of my writing this and its publication.

Contents

Book 2: The Child’s Conception of Space

(Page numbers of the original are shown in italics)

(Page numbers of the original are shown in italics)

PART ONE: TOPOLOGICAL SPACE

I Perceptual space, representational space and the haptic perception of shape

1 Perceptual or sensorimotor space

2 The recognition of shapes (haptic perception)

II The treatment of elementary spatial relationships in drawing. ‘Pictorial space’

1 Space in spontaneous drawings

2 The drawing of geometrical figures

III Linear and circular order

IV The study of knots and the relationship of ‘surrounding’*

V The idea of points and the idea of continuity

PART TWO: PROJECTIVE SPACE

VI Projective lines and perspective

1 Construction of the projective straight line

2 Perspective

VII The projection of shadows

VIII The co-ordination of perspectives*

IX Geometrical sections

X The rotation and development of surfaces

PART THREE: THE TRANSITION FROM PROJECTIVE TO EUCLIDEAN SPACE

XI Affinitive transformation of the rhombus and the conservation of parallels

XII Similarities and proportions

1 Similar triangles

2 The similarity of rectangles

XIII Systems of reference and horizontal-vertical co-ordinates*

1 Horizontal and vertical axes

2 The development of general systems of reference

XIV Diagrammatic layouts and the plan of a model village

1 Locating the doll on the model landscape

2 The layout of the model village

XV General conclusions. The ‘intuition’ of space

Note

* These sections are dealt with at considerably greater length in A Teachers’ Guide to Reading Piaget by M. Brearley and E. Hitchfield (Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1966).

Topological space

I

Perceptual space, representational space, and the haptic perception of shape

1 Perceptual or sensorimotor space

Piaget holds that the child’s building up of a geometrical representation of space develops very slowly, and that for his first perceptions and rudimentary notions of spatial relationships we must turn to the branch of mathematics known as ‘topology’. Although, mathematically speaking, this represents a late and advanced level of theory, it rests on very early modes of perception from which the small child can most readily form his first elementary spatial representations.

These elementary topological perceptions are those of the relations of (1) proximity or ‘nearbyness’, (2) separation, (3) order (or spatial succession), (4) enclosure or surrounding, (5) continuity.

2 The recognition of shapes

The first experiments described are concerned with the recognition of shapes by means of the sense of touch in the absence of visual stimulation (technically known as ‘haptic perception’). The procedure was to present the child with a series of objects in succession—the child being before a screen behind which it feels the objects handed to it. In this way the experimenter is able to observe the methods of tactile exploration employed by the children.

Very young children are first of all asked to identify common objects, e.g. pencil, comb, key, spoon, etc., which they are handed in succession, by selecting corresponding articles from a collection which they can see. Older children are started straight off with a series of cardboard cut-outs in the shape of geometrical figures.

(A) Simple and symmetrical: circle, ellipse, square, rectangle, rhombus, triangle, cross, etc.

(B) More complex but also symmetrical: star, Cross of Lorraine, swastika, simple semi-circle, semi-circle with notches along the chord, etc.

(C) Asymmetrical but with straight sides: trapezoids of various shapes, etc.

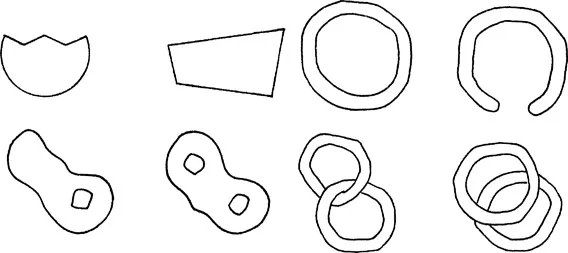

(D) A number of purely topological forms: irregular surfaces pierced by one or two holes, open or closed rings, two intertwined rings, etc. Shapes made of matchsticks stuck on a flat surface and outlines chiselled in the surface of wood were also used.

(B) More complex but also symmetrical: star, Cross of Lorraine, swastika, simple semi-circle, semi-circle with notches along the chord, etc.

(C) Asymmetrical but with straight sides: trapezoids of various shapes, etc.

(D) A number of purely topological forms: irregular surfaces pierced by one or two holes, open or closed rings, two intertwined rings, etc. Shapes made of matchsticks stuck on a flat surface and outlines chiselled in the surface of wood were also used.

Each child was asked to name the object or shape—to identify it among a visible collection or set of drawings or to draw the object it had felt. Thus the problems faced by the child are the translation of tactile kinaesthetic perceptions into visual ones and the construction of a visual image incorporating the tactile data and the results of exploratory movements.

Stage i responses shown by children aged between 2;6 and 4 years old reveal the ability to recognize familiar objects but the inability to recognize shapes for want of sufficient exploration. As the ability to abstract shape develops, topological shapes are identified, but euclidean shapes cannot be reconstructed. The youngest children merely grasp the object to be identified and liken it to a shape possessing whatever characteristic their fingers happened to have touched, e.g. Dan (3;o) when presented with an ordinary semi-circle takes hold of it by one of its corners and identifies it as a triangle. Common objects are recognized by seizing, rolling from one hand to the other, touching, pressing, sticking the finger in the hole of the key handle, etc., but this kind of handling of the whole object is inadequate for the recognition of geometrical shapes.

Fig. 1. Toothed semi-circle, trapezoid, irregular surfaces pierced by one or two holes, open and closed rings, intertwined and superimposed rings. (The Child’s Conception of Space, p. 19.)

Later in this stage children identify topological shapes, e.g., Sim (450) made the correct choice for a circle but was unable to draw it. However, after his hand was guided once, he was able to draw a closed figure by himself. He easily recognized the open ring, the two inter-twined rings, and the irregular surface with one hole. But he refused to locate the triangle among three models comprising a circle, a square and a triangle, although touching the apex with both fingers whilst holding the converging sides between his hands.

This and numerous other examples illustrate the process of abstraction of shape as being achieved by virtue of the actions which the subjects perform on the object, such as following the contour step by step, surrounding it, traversing it, separating it and so on. These relationships of proximity and separation, openness, closure and interlacement take on a far greater importance from the point of view of perception than even the simplest euclidean relationships.

Stage 2 reveals the progressive recognition of euclidean shapes. Exploration is more active, although still haphazard and, as a result, the subject stumbles across a number of clues whose significance he can keep in mind. By means of these he is able to distinguish curved shapes from those with angles and straight lines: e.g. Lou (4;1) recognizes immediately the surfaces with one or two holes, open and closed rings, etc. He recognizes the circle and is able to draw it, also the ellipse. In the drawing of the square one corner is more or less a rightangle, the others shown as curved, but it is only recognized among the models on one of two occasions. Triangles, rhombuses, etc. are all lumped together. For the notched semicircle he draws a complete circle with points added to the circumference.

The drawings of euclidean shapes made by children at this stage are no longer scribbled but tend to look alike. In the main the element of closure is dominant and the drawings tend to express the child’s exploratory movement (all round the edge) rather than his visual perception of straight lines and angles. It is the analysis of angles which marks the transition from topological relations to the perception of euclidean ones.

Substage 2b shows more developed exploration—though not yet complete or systematic—with a resultant progressive differentiation of angular shapes, but no great improvement in their recognition. Also drawing shows an advance but still lags behind recognition. Drawing at this stage expresses not so much the model visually or tactilely perceived as tactile activity itself, e.g. Char (5;2) is successful with simple shapes and is able to recognize the rhombus after a series of explorations. ‘It is two roofs’. He then draws two opposed triangles on a common base. He confuses a curved triangle with the semi-circle.

Mar (5;2) explores the rhombus and says of each side in succession ‘It’s leaning, it’s leaning, it’s leaning, and this is leaning too’.

The child explores everything but, as a result of lack of ope...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- An Introduction to The Child’s Conception of Geometry

- An Introduction to The Child’s Conception of Space