![]()

1

Methods for acquiring and analyzing infant event-related potentials

Tracy DeBoer

University of California at Davis, USA

Lisa S. Scott

University of Massachusetts at Amherst, USA

Charles A. Nelson

Harvard Medical School, USA

A primary goal of developmental cognitive neuroscience is to elucidate the relation between brain development and cognitive development (see Nelson & Luciana, 2001). The study of this relation in children older than 5–6 years lends itself to many of the same tools used in the adult, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). However, in children younger than this, limitations in motor and linguistic abilities, coupled with abbreviated attention spans, make the use of such tools impractical. In contrast, electroencephalography (EEG) and event-related potentials (ERPs) provide some of the only noninvasive methodological techniques in the armamentarium of cognitive neuroscientists that allow researchers to examine the relation between brain and behavior beginning at birth. Both EEG and ERPs measure electrical activity of the brain recorded from scalp electrodes and can be utilized across the entire lifespan, thereby permitting one to use the same methodological tool and dependent measure across a broad range of ages (although comparisons across large age spans may be challenging due to qualitative differences in the EEG and ERP response). In addition, EEG and ERPs do not require an overt behavioral or verbal response and therefore permit the study of phenomena that cannot be studied with behavioral methods (e.g., responses to the simultaneous presentation of multiple stimuli or stimuli presented so briefly as to preclude a behavioral response). However, when a behavioral response is obtainable, EEG and ERPs can also provide an invaluable complement and an additional level of analysis to that behavioral measure by permitting one to glimpse the neural circuits underlying the behavior.

EEG and ERPs both reflect the electrical activity of the brain, and both are collected in a similar manner; however, they represent slightly different aspects of brain function. Whereas EEG is a measure of the brain's ongoing electrical activity, ERPs reflect changes in electrical activity in response to a discrete stimulus or event. ERPs are collected from several trials and then averaged in order to eliminate background noise that is not related to the stimulus of interest. Thus, ERPs are said to be “time-locked” to the stimulus. Both EEG and ERPs contribute to the understanding of brain maturation and cognitive development. EEG provides information regarding the resting state of the brain (as indexed by various EEG patterns or rhythms), synchrony between regions (coherence), or spectral changes in response to a cognitive event (Event-related Synchronization/Desynchronization). In contrast, deflections in the ERP (referred to as components) reflect specific aspects of sensory and cognitive processes associated with various stimuli. Due to the high temporal resolution (on the order of milliseconds), ERPs are well suited to index changes in the mental chronometry of a given neural response.

Although various sources have discussed aspects of electrophysiological research including the historical and neurophysiological background of EEG and ERPs, and issues concerning experimental design, data acquisition, analysis, and interpretation in adult populations in great detail (e.g., Handy, 2004; Regan, 1989), few have addressed utilization of these measures in developmental populations (for an important exception see Taylor & Baldeweg, 2002). This is unfortunate because recording EEG and ERPs in infants and young children differs from recording in adults in some unique ways. Thus, in this chapter we elaborate on the idiosyncrasies of using EEG and ERPs in developmental populations, provide the reader with some practical methodological advice, and call attention to some caveats that arise when using EEG and ERP techniques to investigate the developmental progression of brain–behavior relations early in life. The chapter is designed for the novice developmental EEG/ERP researcher and focuses on issues regarding study formation, experimental design, data collection, and data analysis. The heart of the chapter reviews issues regarding practical acquisition topics such as data acquisition systems, participant selection, data collection (e.g., recording electrophysiological data, artifact rejection, and averaging), and statistical analysis. The chapter closes with an introduction to source separation and localization, as well as challenges and future directions for developmental electrophysiological research.1

STUDY FORMATION AND EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

Hypotheses

Despite increases in the use of EEG and ERPs with developmental populations, several obstacles remain that prevent testable hypotheses from appearing more often in the literature. First, since relatively little is known about the specifics of functional human brain development, it can be challenging to derive concrete hypotheses based on the development of discrete neural circuits. Second, almost nothing is known about how physiologic activity in the developing brain propagates to the scalp surface, and thus we do not know what the relation is between activity in the brain vs. at the scalp. Third, the field has only begun to define ERP components of interest and normative and abnormal patterns of EEG across development; thus much discontinuity remains between age groups and across areas of investigation.

With these caveats in mind, in this chapter we attempt to illustrate the kinds of questions that are particularly amenable to an electrophysiological investigation with developmental populations. We also challenge researchers to perform the appropriate exploratory investigations to ensure that more theoretically driven experiments with testable hypotheses can be conducted.

Task design

Due to the limited attentional capacity and restricted behavioral repertoire of infant populations, several considerations may be necessary when designing an experiment. Some developmental EEG/ERP tasks can be derived from tasks used with adults that are adjusted to take developmental differences into consideration (e.g., decreasing the length of the trials, the number of independent variables, or the complexity of the stimuli). However, as accommodations such as these are made, it must be acknowledged that infants are not typically tested under the same conditions as adults (e.g., infants do not benefit from instructions, whereas older children do) and, therefore, direct comparisons across large age differences are often difficult to interpret. Other age-appropriate tasks can arise from modified versions of behavioral tasks known to tap certain cognitive functions of interest (e.g., speech discrimination tasks, approach–withdrawal tasks, habituation tasks, or recognition memory tasks).

Many developmental EEG studies to date have compared spectral activity of children with typical cognitive development to that of clinical groups under a variety of circumstances. Common paradigms involve recording resting EEG while infants watch objects such as brightly colored balls tumbling around a bingo wheel, abstract patterns on a video display, or bubbles, for various amounts of time (e.g., Calkins. Fox, & Marshall, 1996; Marshall, Bar-Haim, & Fox, 2002). Additionally, EEG can be recorded during prolonged events such as games of peek-a-boo or a stranger entering the room (e.g., Buss, Malmstadt Schumacher, Dolski, Kalin, Hill Goldsmith, & Davidson, 2003; Dawson, Panagiotides, Klinger, & Spieker, 1997) or emotion-eliciting videos or musical clips (Jones, Field, Fox, Davalos, & Gomez, 2001; Schmidt, Trainor, & Santesso, 2003) as long as precautions are made to minimize movement on the part of the participant.

On the other hand, as mentioned above, ERPs are by definition timelocked to the presentation of a stimulus. Therefore, in both adult and developmental populations, more stringent constraints are placed on the types of tasks amenable to ERP experiments. To date, most developmental ERP studies have used either the standard oddball paradigm or a combination of the oddball paradigm with an infant habituation paradigm. In the former, two or more discrete stimuli (i.e., typically 500 milliseconds in duration) are presented repeatedly, but with different frequencies. For example, in one study 4- to 7-week-old infants were shown pictures of checkerboard patterns and geometric shapes. ERPs were recorded while one stimulus was repeated frequently (80% of the time) and the other stimulus was presented infrequently (20% of the time, Karrer & Monti, 1995). In contrast, the combined oddball/habituation paradigm involves first familiarizing or habituating an infant to a stimulus (e.g., a face), and then presenting a series of stimuli, consisting of the now familiar stimulus and a novel stimulus (e.g., a new face) repeatedly with equal frequency (i.e., 50% of the time for each) while ERPs are recorded (e.g., Pascalis, de Haan, Nelson, & deSchonen, 1998).

IMPORTANT CONSIDERATIONS IN DEVELOPMENTAL POPULATIONS

Beyond paradigm considerations, one must also consider (1) age-related changes in EEG or the morphology and timing of ERP components of interest, and (2) changes in behavioral measures, including the availability, quality, and validity of these measures.

Developmental changes, which are apparent in both EEG rhythms and the morphology of the ERP waveform, are often difficult to describe, and increasingly difficult to explain due to their complex and multifaceted nature. For instance, major developmental changes in synaptic density, myelination, and other physical maturational processes (e.g., changes in skull thickness and closing of the fontanel) may combine to influence amplitude and latency across different ages (Nelson & Luciana, 1998; see also Chapter 11, this volume, for further discussion).

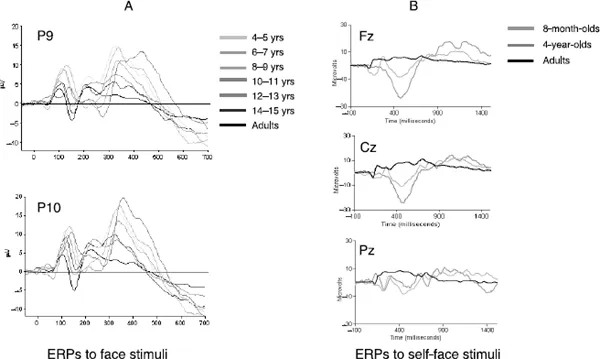

Although great strides have been made in documenting changes in EEG over the first few years of life, much less is known about the developmental trajectories of ERP components (although see Webb, Long, & Nelson, 2005, for an exception). For example, the same EEG frequency bands are typically present throughout development, yet high-frequency bands tend to increase in relative power with increases in age (especially in the band of 6–9Hz: Marshall et al., 2002; Schmidt et al., 2003; see also Taylor & Baldeweg, 2002, for a review). ERP components tend to vary considerably in both form and function across development. Unexpectedly, ERPs of adults and newborns are similar to each other in amplitude, but very dissimilar compared to ERPs from older infants and young children (see Figure 1.1 for illustration). Furthermore, in the first two years of life, reduced synaptic efficiency results in greater slow wave activity rather than peaked activity, the latter being more typical of adult ERPs. Thus, the infant ERP does not show as many welldefined peaked responses (especially in anterior components) when compared to adult responses. The characteristics of the peaked adult waveform typically begin to emerge when children reach 4 years of age, and continue to develop well into adolescence (Friedman, Brown, Cornblatt, Vaughan, & Erlenmeyer-Kimling, 1984; Nelson & Luciana, 1998). In fact, because the distribution of activity across the scalp (i.e., topography) changes with age, we can infer that important changes are still taking place in the neural substrate generating the components of interest throughout development. Amplitudes may also vary as a function of differing task demands imposed on the participant. Presumably the easier the task, the less effort expended, and the less cortical activation required, which may ultimately result in smaller amplitudes (Nelson & Luciana, 1998). Finally, the general heuristic for changes that take place from early adulthood to later adulthood is that, overall, latencies of several ERP components appear longer and amplitudes appear smaller (see Kurtzberg, Vaughan, Courchesne, Friedman, Harter, & Putnam, 1984; Nelson & Monk, 2001; and Taylor & Baldeweg, 2002 for further discussion).

A major change that also occurs with increasing age is the ability to “ground” the measure in behavior or correlate the brain's electrophysiological response with task performance. Infant EEG/ERP paradigms by necessity do not involve issuing instructions, nor do they require an overt behavioral response. However, most adult ERP paradigms include both instructions and a behavior response (even if only to ensure continued attention to the task). Therefore, due to the differences in testing conditions it is possible that, at some level, differences in ERP morphology are due to differences in task requirements.

The “passive” viewing paradigm (i.e., one in which no instructions are given) is useful for two reasons. First, developmental populations can be tested and their data can be compared to those of adults without modification to the paradigm. Second, passive paradigms may evoke basic perceptual components, without the added activity (or noise) that may be recorded when the participant is engaged in some task and/or a behavioral response is required. The drawback to using a passive task is that it is difficult to determine whether participants maintain attention throughout the task, or whether they are doing the task at all. Depending on the specific hypotheses, one must use other means of monitoring attention, for example in visual paradigms, videotaping participants to ensure they were looking at the stimuli, and/or repeating trials in which it was obvious the participants were not attentive. For auditory studies, attention may be a different issue, as ERPs are often recorded during sleep (e.g., deRegnier, Nelson, Thomas, Wewerka, & Georgieff, 2000). During these paradigms, infants may need to be monitored continuously as changes in sleep states (active vs. passive) are thought to influence the ERP response (cf. Martynova, Kirjavainen, & Cheour, 2003).

Figure 1.1(A) Grand averaged ERPs from posterior, inferior temporal electrodes P9 (left parietal lobe) and P10 (right parietal lobe) in response to face stimuli for seven age groups. (B) Grand averaged ERPs from midline electrodes taken from a pilot study in which 8-month-olds, 4-year-olds, and adults passively viewed images of their own face in the context of a face recognition task. Figure 1.1A kindly provided by Dr Margot Taylor (Centre National Cervau et Cognition, Toulouse, France) and Figure 1.1B provided by Lisa S. Scott (Institute of Child Development, University of Massachusetts, Amherst. USA). Visit http://www.psypress.co.uk/dehaan to see this figure in colour.

Although below the age of 4–5 years traditional button-press responses cannot be used, there are some behavioral measures that have been used previously in developmental populations in conjunction with EEG and ERPs. The most informative behavioral measures are those that can be recorded concurrently and therefore directly correlated with the electrophysiological response. For example, in one EEG investigation (Dawson et al., 1997), infants were exposed to several conditions designed to elicit positive and negative emotions while EEG activity was measured (e.g., peek-a-boo with their mothers vs. being approached by a stranger). EEG activity was subsequently analyzed during periods when infants were displaying prototypic expressions of emotions. Results from this investigation indicated that, compared with infants of nondepressed mothers, infants of depressed mothers exhibited increased EEG activation in the frontal but not parietal regions when they were expressing negative emotions.

Due to temporal limitations, recording behavior in co...