eBook - ePub

Fragmentation in Archaeology

People, Places and Broken Objects in the Prehistory of South Eastern Europe

- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Fragmentation in Archaeology

People, Places and Broken Objects in the Prehistory of South Eastern Europe

About this book

Fragmentation in Archaeology revolutionises archaeological studies of material culture, by arguing that the deliberate physical fragmentation of objects, and their (often structured) deposition, lies at the core of the archaeology of the Mesolithic, Neolithic and Copper Age of Central and Eastern Europe.

John Chapman draws on detailed evidence from the Balkans to explain such phenomena as the mass sherd deposition in pits and the wealth of artefacts found in the Varna cemetery to place the significance of fragmentation within a broad anthropological context.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Fragmentation in Archaeology by John Chapman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

INTRODUCTION

Clearing the ground

What we think we know about Balkan prehistory

Human bones, animal, bird and fish remains, seeds of weeds and cereals, legumes and fruit pips, scraps of textiles, loom-weights and spindle-whorls, bone and antler artefacts, ornaments of shell, amber and stone, ground and polished stone tools, lithics, broken sherds and complete pots, figurines, pintaderas and incised signs, metal objects – mostly copper, with some lead, silver, antimony and gold. Objects whose function(s) is (are) known; objects whose function(s) remain(s) unknown. Contents of most of the artefacts – unknown. Meaning of most objects – unknown. Or unknowable? Contexts of discovery – variably recorded – far more settlement than ceremonial monument. Pit finds, house finds, settlement finds; few enclosures, shrines, caves or cemeteries. Mode of deposition – generally unknown but presumed to be refuse disposal. Remains of structures, ditches, pits, palisades, hearths and ovens, pavements and earth floors.

Balkan later prehistory. Rich but unpromising material, first synthesised by Childe (1929). Most Mesolithic, Neolithic and Copper Age ‘cultures’ fall within middle-range societies – more complex than bands, less complex than states. Interpretative battle over designation of ‘cultures’ as tribal units or chiefdoms. A political history of fragmentation (‘Balkanisation’, the ‘shatter belt’) by language, ethnic group and religion, forming mostly mutually exclusive groups, now recapitulated in archaeological terminology and explanation. A proliferation of regional cultures defined not only with reference to national boundaries and ideals but also in traditional terms, with invasions as the most significant source of change. Nationalist agendas configuring key past developments as an achievement of their direct predecessors, as in Piggott’s (1969: 559) ‘national aceramic neolithic competition’, or the glory reflected by supernovae of European significance such as Lepenski Vir and the Varna goldwork.

These introductory notes summarise the material culture of later Balkan prehistory and the drift of some of the stories archaeologists have told about this material. But what is significant about the later prehistory of the nation-states of Albania, Bosnia/Hercegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, FYROM, parts of Greece, Hungary, Moldova, Romania, parts of Russia, parts of Slovakia, Slovenia, parts of European Turkey, Ukraine, Yugoslavia that we can talk about the whole region in a single breath? It may be that there is no consensus about the term which best describes an area known variously as the ‘Balkans’, or ‘south-east Europe’ or ‘central and eastern Europe’. But we can define the boundaries of the region clearly: the western boundary is the Adriatic, the eastern the Black Sea, the southern the northern edge of the Mediterranean zone and the northern border the Carpathian chain.

Furthermore, there is an overall sense of uniformity in the material culture and lifeways of this region that enables us to talk coherently about its Mesolithic, its Neolithic and its Copper Age. The most striking feature which differentiates the study region from the succeeding Bronze Age and from the Neolithic of much of northern and western Europe (but not that of central Europe or Greece and Anatolia!) is the importance of the domestic domain and the relative insignificance of the mortuary domain and any accompanying monumentality. There are ample examples of regional groups whose communities lived in villages rather than hamlets and, on occasion, what appear to be substantial sites the size of ‘towns’. The second characteristic of this study region is the high density and immense variety of artefacts deposited, for the most part, in the settlements. This trait differentiates the Balkan Mesolithic, Neolithic and Copper Age (henceforth MNCA) from all bordering Neolithic and Copper Age groups except two – those of Greece and Anatolia. The Greek and Anatolian Neolithic communities share many social practices with those of the Balkans (not least tell settlement) but the impact of Mediterranean ecology on lifeways, on food and drink and on house construction allows differentiation at the tertiary level from societies in the Balkans. As we shall see in this book, the resultant material residues are both striking and diverse and form one of the principal challenges to understanding the Balkan MNCA past.

Time/space framework

The Balkan MNCA has developed a (largely justified) reputation for terminological complexity, partly because of the variety of languages spoken in the study region and partly because of the diversity of material culture. But there is also a third factor influenced by both the others – the tendency of Balkan prehistorians to be taxonomie ‘splitters’ rather than ‘lumpers’, preferring to divide material culture into diverse small units rather than to ignore minor facets of diversity in favour of a generalising integration of finds and site types. Thus, two adjoining material assemblages manufactured by the first farmers in Romania and Hungary are termed ‘Criş’ in Romania, ‘Körös’ in Hungary, even though the similarities of most artefact types far outweigh the differences. The same is true of the two striking assemblages of painted pottery of the climax Copper Age assemblages found in Romania and the former Soviet Union (now Moldova and Ukraine). The term ‘Tripolye’ has always been used in the former USSR, the term ‘Cucuteni’ in Romania; although the painted wares are internally homogeneous and externally differentiated from all other ceramics, the terms continue in use, each based upon equally impressive eponymous settlements. Undergraduates studying this region regularly undergo intensive atlas training sessions to be able to comprehend the basic terminological nuances embodied in the specialist literature!

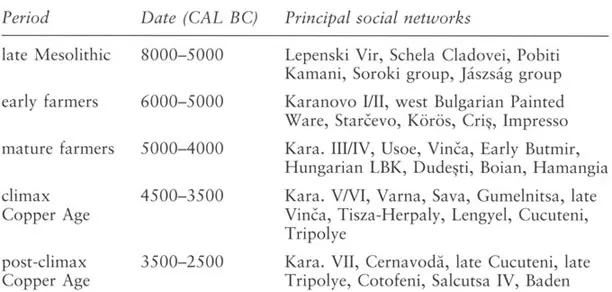

In this book, I shall forgo such fine divisions between social groupings in favour of a broad categorisation into five stages (Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Stadial development of the Balkan Mesolithic, Neolithic and Copper Age

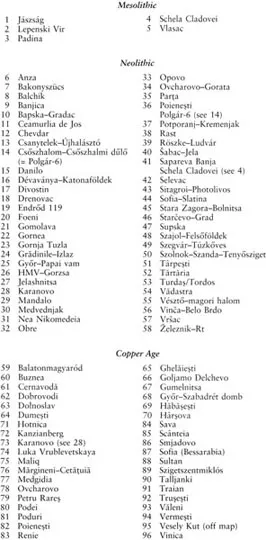

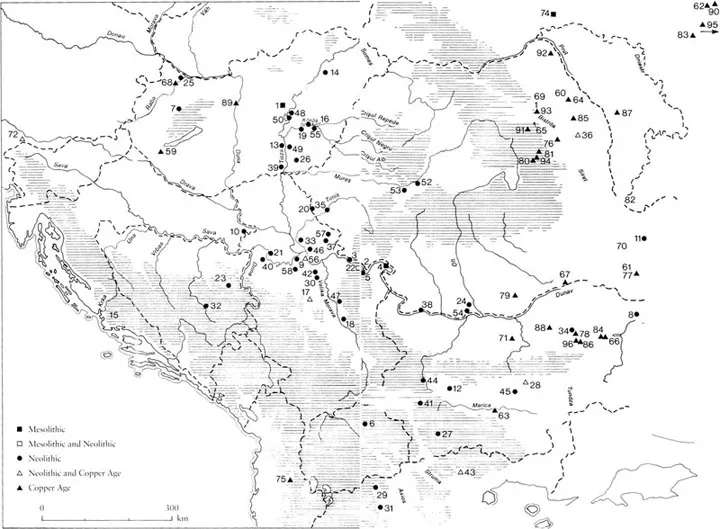

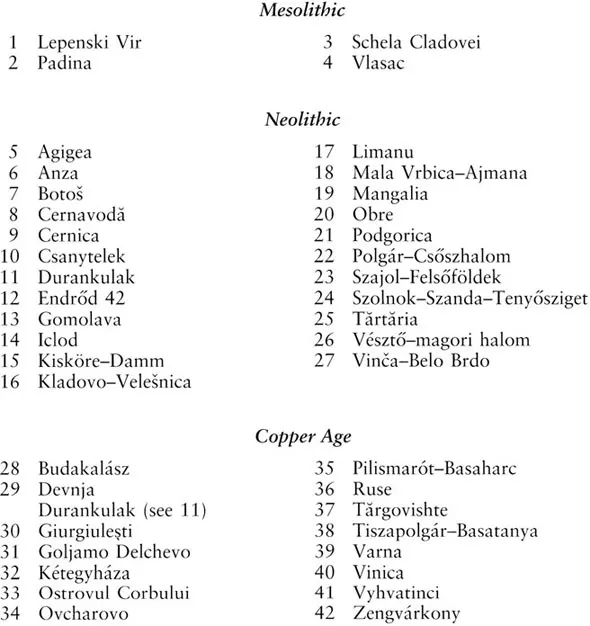

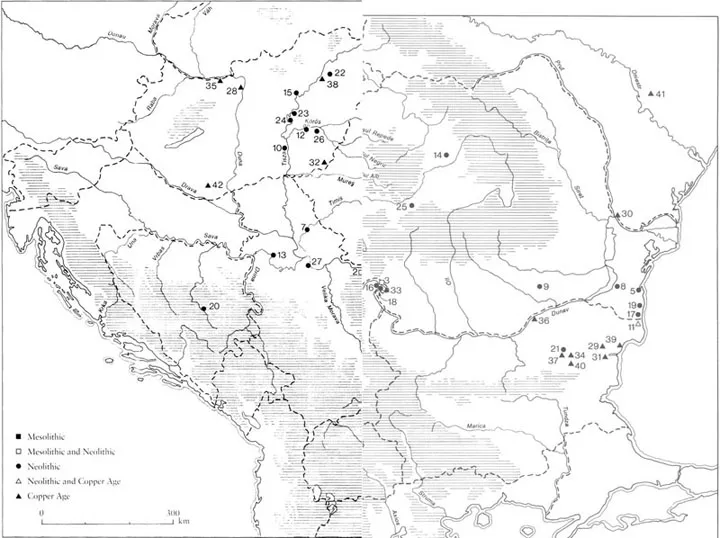

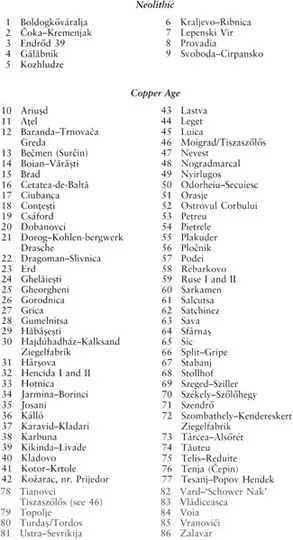

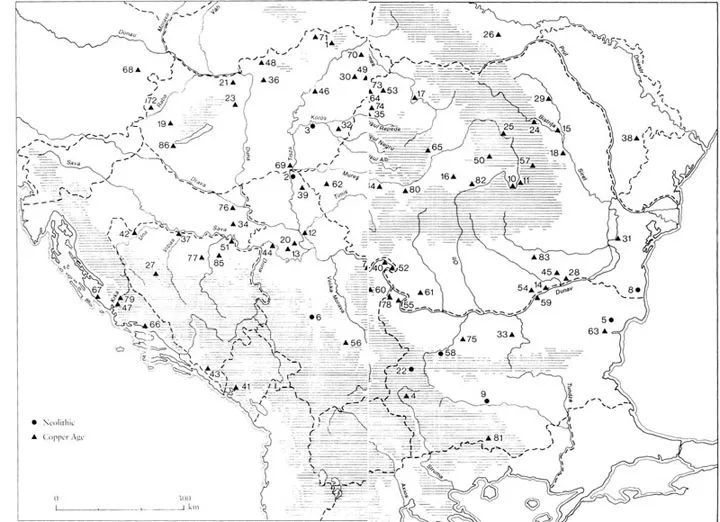

This scheme loses in over-generalisation what it gains in parsimony and elegance. There is also a further drawback – communities living in different regions at the same time are not always at the same ‘developmental stage’. Hence, despite its appearance, this scheme is not based upon the questionable assumptions of an outmoded social evolutionary perspective but is rather a descriptive scheme enabling readers to navigate the choppy seas of Balkan prehistoric terminology. The main advantage of this generalised chronology is that it permits systematic comparison of broad trends in the social practices which are central to this book. I have provided a gazetteer (pp. 234–45), where each term in common usage for a specific social grouping or network (often called ‘culture’) is defined in terms of its spatial distribution by country and its existing 14C dates or, in their absence, an estimated timespan. All dates used in this book have been calibrated using the OxCal programme v. 2.18. Readers requiring traditional typologically based chronological information are directed to the (regrettably ‘14C-free’) synthesis by Parzinger (1993). The distribution maps of all sites and monuments mentioned in the text are presented at the end of the chapter (Fig. 1.1, settlements; Fig. 1.2, burial sites; Fig. 1.3, hoards).

Figure 1.1 Map of Mesolithic, Neolithic and Copper Age settlements

Figure 1.2 Map of burial sites, Balkan Mesolithic, Neolithic and Copper Age

Figure 1.3 Map of Balkan Neolithic and Copper Age hoards

A theoretical framework

But how can we know more of the communities who deposited so many artefacts on so many settlement sites? This book developed out of a fascination with the wealth of objects which have been found in the settlements and cemeteries, the hoards and the shafts, the rivers and the landscapes of central and eastern Europe. These objects are, after all, what most distinguish the Balkan MNCA from other Neolithics in Europe – especially those dominated by public ceremonial monuments. I believe that careful typologies of the artefacts and ecofacts, meticulous social analysis of the people and insightful hermeneutic appreciations of places are necessary but insufficient research directions for an understanding of these millennia. What has been missing in Balkan prehistory is an awareness of the structural relationships between people, objects and places and the material dimensions of these relations in social practices. If the identities of people are mutually constituted by the objects which they use and the places which they inhabit, the material environment is the active, structuring matrix for such constitution: active, in so far as the matrix is constantly changing – within limits – in the flux of everyday living; structuring, because material objects in place form local histories which influence future action. Here, the continuum between permanence and mobility takes on great significance: because, in much of the MNCA, it is domestic buildings and sites which are the most permanent parts of the material environment, the social practices in villages and hamlets act as constant sources of renewal by grounding people in their pasts. The longer a site is inhabited, the more important local place becomes as a key element in the maintenance of cultural memory.

The starting-point for the understanding of social practices is the challenge to the widespread notion that archaeology is the science of rubbish. This notion is based upon a twentieth-century consideration of rubbish as that whose use-life is over and, being contaminated, must be spatially separated from everyday living areas. This idea reduces the importance of discarded rubbish and diminishes the significance of the means of disposal. It is part of an approach to archaeology which takes the production of artefacts as an impersonal, ergonomic relationship between living humans and inert matter, and the distribution of objects as a process of the exchange of goods for goods, valuables for prestige items.

An alternative approach questions the gap between people and objects and relates the development of people to their objectification through artefacts. If objects are not as distinct from people as was once believed, the creation of objects contains within it an aspect of personhood which endures as long as the object remains inalienable. Thus the idea that objects are reproduced rather than produced implies the personal contribution to the value of an object, which is closely related to the value of the person involved. The exchange of inalienable objects means that an indissoluble link exists between all owners or users of an artefact and the artefact with its distinctive biography. Thus, people are exchanging themselves as they exchange polished stone axes and painted ceramics, and the succeeding chain of personal relations through exchange, which will be termed ‘enchainment’, is a fundamental part of social life. There is a constant tension between the person as an ‘individual’ and the person as a ‘dividual self’, enchained to many people depending on context. As regards deposition of objects, it may be proposed that ‘rubbish’ is no more dead than the newly deceased are dead but that, like the ancestors into whom the newly dead are transformed, objects that are deposited continue to hold a certain significance for the living. Thus, objects created in the domestic context do not easily lose their domestic meaning and significance, even in ‘death’. These ideas of the close links between people and objects provide a general framework for the understanding of the object-rich deposits of the Balkan MNCA, which enables discussion of the close similarities between social practices involving human bodies and objects.

We can identify three groups of social practices which I believe are fundamental to the workings of the Balkan MNCA. The first group relates to places in the landscape: dwelling and intra-mural burial in specific places and/or community areas with distinct links to ancestral space; the occupation of ancestral places such as tells; and the creation of a distinct mortuary domain as a counterpoint to the domestic domain. The second group is concerned with distribution: the creation, maintenance and development of social relations through the enchainment and accumulation of personalised objects; the fragmentation of objects and humans as a major aspect of enchainment; and the creation of object sets as part of accumulation. The third group is concerned with deposition: the general retention of domestic objects in the immediate vicinity of the living area during and after their use-life; the structured deposition of objects and/or human remains and/or burnt material in specific places; the exchange of the materials of the living with those of the ancestors through pit digging, house burning and related activities.

In this book, I shall develop the theme that enchainment and accumulation are the two main practices which sustain social relations in the Balkan MNCA. The exchange relations linking dividual persons through material culture are anything but egalitarian and contain the potential for asymmetrical relations, indebtedness and long-term dependence if the constraints upon accumulation are circumvented. The rarity of hoards in the Balkan Neolithic is a sign that accumulation is carefully controlled both at the individual and the household level. But, in the Copper Age, the introduction of two new metals – gold and copper – provides the opportunity for differential acquisition of these materials by exchange. It is significant that the acquisition of non-local metals is far more desirable than the use of locally won minerals and ores. It is also evident that the greatest concentrations of the new metals appeared in the mortuary domain, outside the control of the community or household leaders in the settlements. But one of the most important reasons for the importance of copper and gold relates to their physical properties in respect of fragmentation.

The mechanism for enchainment through fragmentation can be summarised as follows. The two people who wish to establish some form of social relationship or conclude some kind of transaction agree on a specific artefact appropriate to the interaction in question and break it in two or more parts, each keeping one or more parts as a token of the relationship. There may well be limits of size on how often a single object can be successively fragmented to maintain the impetus of the enchained relationship. Thus, the part of the object may itself be further broken and part passed on down the chain, to a third party. The fragments of the object are then kept until reconstitution of the relationship is required, in which case the part(s) may be deposited in a structured manner. The example of the enchained relations between the newly dead and a close kin amongst t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Halftitle

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1. Introduction: Clearing the ground

- 2. Two Ways of Relating: Enchainment and accumulation

- 3. Broken and Complete Objects

- 4. Hoards and Other Sets

- 5. People, Cemeteries and Personal Identities

- 6. People and Places in the Landscape

- 7. Summary and Conclusions: Towards an archaeology of social practices

- Gazetteer of Time/Space Distributions of Cultural Groupings

- Appendix: Neolithic and Copper Age hoards

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index of Sites

- Index of Authors

- General Index