![]()

Part I

Introduction

![]()

1 The Puzzle of Handedness and Cerebral Speech

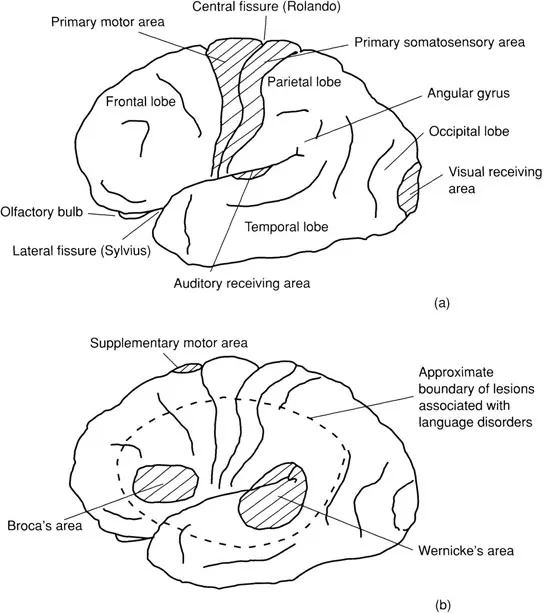

This book is about differences between humans for handedness and for brain asymmetry. It has been known at least since the time that Galen was a surgeon to the gladiators in Rome that each side of the body is controlled by the opposite side of the brain. It was not until the mid 19th century that Paul Broca proposed his famous rule, “On parle avec l’hémisphère gauche” (Broca, 1865). Broca had performed post mortem examinations on a number of patients who had lost their ability to speak but were able to understand speech. He found lesions in the left frontal lobe in all cases. A few years later, the Austrian neurologist Carl Wernicke described another type of speech disorder in which patients produced a stream of fluent speech that was incomprehensible, and the patients themselves could not understand what was said to them. The cerebral lesion in these cases was in the region of the superior gyrus of the temporal lobe, again on the left side. Figure 1.1 illustrates some key features of the human cerebral cortex and the regions now known as Broca’s and Wernicke’s areas. Disorders of language may be associated with lesions over a wide area of the left cerebral hemisphere, with varying patterns of loss of function.

Figure 1.1 | (a) Human cerebral cortex, lateral view; (b) language associated cortex. |

The left cerebral hemisphere was called “dominant” by neurologists when it was realised that for most people it is the side that controls both speech and the preferred hand, the right. By contrast, the right hemisphere seemed to have no major function and was termed “minor” or “non-dominant”. The only disorders that were clearly linked to lesions of the right hemisphere and not the left were forgetting how to get dressed (dressing apraxia) and curious disorders of awareness of the left side of space, left-sided neglect (Brain, 1941). One of the main pursuits of modern neuropsychology has been to show that the right hemisphere has its own special functions, albeit ones not dependent on language. The split-brain operations of the 1960s confirmed that there is a pattern of cerebral specialisation, present in most people, the left brain for speech and language and the right brain for certain types of nonverbal functions. The latter include skills that cannot be put into words easily, such as recognising faces, understanding spatial relationships and interpreting non-speech sounds. The nature of cerebral specialisation continues to be explored, as will be considered further throughout the text. As a starting point, the term “cerebral dominance” (CD) will be used to refer to “the cerebral hemisphere that serves propositional speech”, that is, the ability to express ideas in spoken words.

What has been greatly underestimated in accounts of brain specialisation, in both popular and scientific literature, is the extent to which people differ for these key asymmetries of hand and brain. We know that some people are left-handed and also that some people have CD on the right side. Do the two atypical asymmetries go together? They do not. What rules govern their association? This question was of particular interest to some of the founders of modern neuropsychology (Hécaen and Piercy, 1956; Luria, 1970; Zangwill, 1960). The question became unfashionable as researchers sought for more detailed and universal specifications of left brain versus right brain functions. The puzzle of the relationship between handedness and cerebral dominance is the focus of the research described in this book. The puzzle leads to other questions about human evolution, genetics, brain and nervous system, skill, intelligence and mental illness. The purpose of this book is to outline my findings and conclusions to date.

My research on relationships between hand and brain asymmetries began some 40 years ago. It is a continuing detective inquiry that has followed certain principles. The first principle was to practise systematic doubt because the literature was already vast before the explosion of research since the 1960s. It seemed to me that there was more myth than fact, more speculation than evidence, in what was written about handedness. I saw my task as to strip away the many layers of opinion and surmise, to discover the key facts. As in an archaeological dig, I aimed to discover the bare bones from which a secure reconstruction could then be attempted. However, speculative theories continued to grow at a great rate, like the dragon’s teeth that turned into warriors faster than they could be slain. Even worse, elements of my own theory became embedded in new theories in ways that glossed over key points. This led to inaccurate accounts of my theory in the literature. In order to understand the right shift (RS) theory, it is necessary to follow each step of the detective trail, as explained in the sequence of chapters of this book. A new map must be drawn. A few changes to the old map will not do. However, for readers who prefer to read their detective stories knowing the solution to the mystery, the last chapter summarises the key facts and assumptions.

The second related principle of the detective inquiry was that my theory must rest on evidence that was highly reliable. Each stage of the argument depends on empirical research, the chief findings tested by replication before they were accepted. At each critical stage for the theory, there was some mathematical regularity. This was often surprising, but led to new and productive ways of looking at the data. The building blocks of the RS theory are tied together through reliable quantitative relationships. It was the quantitative analyses that revealed links between the evidence from neurology to genetics, from genetics to ability, and from neuropsychology to mental illness. To one commentator (Michel, 1995), the theory is reminiscent of Dr. Pangloss, Voltaire’s optimistic philosopher. This would be true if the theory were just a hopeful story. On the contrary, the theory was discovered through empirical research and analysis over many years. It was because the numbers fitted that the theory seemed to me logically necessary, not just a plausible tale. For readers who are maths aversive, numbers will be relegated to appendices when possible. It is important to understand, however, that the theory is supported by quantitative analyses that agree with its predictions.

The mutual interplay of theory and data in the advance of knowledge is an interesting topic for the philosophy of science. It touches on the present work in several ways. I have collected empirical data on as large a scale as feasible, not just for the sake of counting, but because I believed that handedness needed investigation as a feature of human biology, using samples representative of the population. Because the atypical patterns of interest are relatively infrequent, samples must be large to make reliable estimates of frequencies. The empirical data gathering was guided by specific questions. To those who suppose that theoretical pre-conceptions might have biased the research process, I would point out that the most interesting outcomes were often the most surprising. It is the “happy surprises” or “aha!” experiences that make scientific research worthwhile. The RS theory rewarded me with several. Popper (1963) pointed out that no scientific theory is ever “proven” because it might yet be bettered by a more comprehensive theory. However, a sense of scientific progress depends on finding puzzle pieces that seem to drop into place. The new or improved picture is a pleasant surprise but does it make sense in the light of the pieces assembled before? Do previous assumptions need reappraisal? What does the new puzzle edge suggest about the next pieces to look for? The RS theory has been fruitful because it suggested how some old puzzles could be solved and then led to new questions that gave further happy discoveries in their turn, sometimes many years later. The RS story depends on a dialectic interplay between new findings and developing theory. It was not dreamt up in a single act of creative imagination.

A major change in the scientific picture is what Kuhn (1970) called a paradigm shift. The RS theory leads to a new way of looking at handedness and cerebral dominance. Its main innovation, the idea that chance plays a key role in the determination of asymmetry, is now commonplace in theories of handedness. However, alternative theories use the chance postulate in ways that differ from the RS theory. Some try to assimilate it to more traditional paradigms, as will be considered in chapter 16. Psychologists face particular problems in their philosophy of science, partly due to the inherent difficulties of doing psychology scientifically, but also due to the statistical strait-jackets they have adopted as guarantees of scientific respectability. If a result is “statistically significant” at the 5% level, it is worth attention, otherwise not. The argument for statistical significance depends on the idea that the result should not have occurred “by chance” more frequently than 5 per 100 (or 1 in 20) times. The RS theory suggests that the effects that need to be investigated occur against a universal background of chance asymmetries. It is not surprising if effects are difficult to detect. Some reliable trends, such as the slightly greater frequency of left-handedness in males than females, or in dyslexics than non-dyslexics, are not likely to be statistically significant unless samples are very large. However, the direction of trends is often consistent over studies. The RS theory does not depend on a single test of statistical significance, but rather on a body of interrelated evidence that suggests a new way of approaching questions about hand and brain asymmetry. Reports of “failures” of the RS theory are considered in chapter 15.

Handedness and Cerebral Dominance as a Problem in Neurology

The rule that humans tend to depend on the left cerebral hemisphere for the control of speech was probably discovered by a French country physician, Marc Dax, but it was not recognised by neurologists until its formulation by Broca (Critchley, 1970). Modem brain imaging techniques show that both hemispheres are activated during speech, but the left typically more extensively than the right (Frackowiak, 1994). Most treatments of cerebral specialisation assume that the left hemisphere speech rule is so general that exceptions can be safely ignored. Or if there is some doubt, it is considered sufficient to restrict research samples to right-handers, often males only, in the belief that unwanted variability will be avoided. This view is almost certainly mistaken. The natural variability of the general population is greatly under-estimated.

How were exceptions to the classic rule regarded by neurologists? There is some dispute about Broca’s own views. Eling (1984) describes Broca’s original paper as discussing the existence of exceptions for speech laterality, just as there are exceptions to the rule of right-handedness, and warning the reader not assume that the two exceptions go together, “Because it seems to me absolutely not necessary that the motoric part and the intellectual part of each of the hemispheres are solidary to one another” (Broca, 1865, p. 386). Harris (1991) argued that the balance of Broca’s later writings on this point suggests that he inclined to the mirror-reversal or opposite rule, that left-handedness would go with right-brainedness as right-handedness goes with left-brainedness. Whatever Broca actually believed, and in spite of many publications on “exceptions” to the opposite rule, the belief that hand and brain asymmetry “ought to go together” is so compelling that it continues to dominate accounts of handedness and brain asymmetry. It was asserted recently by the medical correspondent of The Times newspaper.

The search for rules of association between speech side and handedness depends on exceptions, people with disorders of speech (dysphasias) following right-sided brain lesions and left-handers with unilateral cerebral lesions of the speech areas in either hemisphere, with or without dysphasia. Cases of interest are infrequent in the experience of any one clinician, but many individual case reports were published in the medical literature. Goodglass and Quadfasel (1954) found 110 cases of left-handers with unilateral lesions of the speech areas described in the literature, and added 13 cases of their own. The speech hemisphere was the left in 53% and the right in 47%. They concluded that, “the tendency for language to centre predominantly in the left hemisphere is in large measure independent of handedness” (p. 531).

There are several difficulties about evidence drawn from cases in the literature. Reports are more likely to be published if cases are deemed interesting, so there is a danger of selection bias. Unusual cerebral laterality may be missed by clinicians in the same way that infrequent and unexpected signals are often missed. There was an important problem due to prejudices against the use of the left-hand for writing, eating and other “visible” actions. Until about the mid 20th century these pressures were severe. Neurologists were aware that most left-handers had been forced to use the right-hand, and had become what they termed “shifted sinistrals”. Hence, neurologists searched for any evidence of left-handed tendencies in the patient and relatives. It was not realised that such a search will reveal some evidence of non-right-handedness in about half of the population (see chapter 2). Thus, neurologists came to believe that right CD does not occur in right-handers, but only in left-handers. On the contrary, the RS analysis led to the very surprising idea that people with right CD should include more right- than left-handers (see chapter 4).

What theories were proposed as to the speech laterality of left-handers? There are five logically possible alternatives, right, left, either, both or some combination of these, listed in Table 1.1, along with their proponents. The classic “opposite” rule (speech in the right hemisphere contralateral to the preferred left-hand) will not do because, as shown by Goodglass and Quadfasel above, left CD is at least as frequent as right CD in left-handers. If the speech hemisphere is independent of handedness, then left CD should be as prevalent in lefthanders as in right-handers, but this is not true. Penfield and Roberts (1959) supported the “left for everyone” rule because they found very few cases of right CD (1.5%) among their series of patients undergoing elective brain surgery for the treatment of epilepsy. However, they disregarded several cases of brief speech disturbance that they attributed to “articulation” problems only. The “either hemisphere” rule was suggested by Chesher (1936) for people with mixed-hand preference; definite left-handers were expected to follow the contralateral rule. Bingley (1958) supported the “either” rule for all left-handers. In his own sample there were approximately equal numbers with left and right CD, as in the literature. The “both” rule, or the “bilateral speech” hypothesis, seems to have been prompted by a report that speech disorder was more frequent in left-handers (38%) than right-handers (26%) among German World War Two (WW2) head injury cases (Conrad, 1949). Speech disorders were also considered more often transient in left-handers. The bilateral speech hypothesis was strengthened by a report that left-handers were more likely than right-handers to experience speech disorders during epileptic auras (warnings of attack) independently of the hemisphere affected (Hécaen and Piercy, 1956). Finally, a combination of these theories acknowledges that left-handers may have right or left or bilateral speech, in proportions unknown.

Table 1.1 Hypotheses for the cerebral speech of left-handers

Right | Classic contralateral rule |

Left | Goodglass and Quadfasel (1954) Penfield and Roberts (1959) |

Either | Bingley (1958) Chesher (1936) Humphrey and Zangwill (1952) |

Both | Conrad (1949) Hécaen and Piercy (1956) |

Some combination of the above | Roberts (1969) Zangwill (1960) |

How can progress be made on this question? Oliver Zangwill (1967) realised that the problem should be studied as one of human biology, in samples representative of the general population, not ad hoc collections of clinical cases. What was needed was a series of cases with strictly unilateral brain lesions, studied for speech disorder and for handedness, but drawn from the population in such a way that inclusion in the series was independent of handedness or lesion side. (Of course patients with brain injuries are not representative of the general population after their injury, a point that worried some of my students, but they were representative before their head injury, in consecutive series of stroke patients seen in a neurology service, or service personnel with war wounds.) Five series that met these criteria of impartial selection were found. The combined data confirmed that handedness and speech laterality are not independent. The left hemisphere rule for all will not do because left-handers are more likely to have right CD than right-handers. However, right-sided speech was not the norm for left-handers. Details of the five series will be considered in chapter 4 because their further analysis was of great importance for the development of the RS theory. For the present, we should note an important problem for research that incidences of left-handedness in the several series differed markedly. This raises the fundamental question of how reliable data can be collected on a characteristic that is measured in different ways by different investigators.

The evidence as to speech laterality above depended mainly on clinical inference and post mortem studies. Direct assessments of speech laterality in living patients were first made by stimulating the exposed cortex with a brief electrical pulse during operations for the relief of epilepsy at the Montreal Neurological Institute (Penfield and Roberts, 1959). Before removing tissue thought to be causing the epilepsy, surgeons needed to ensure that it was not critical for speech. A technique for a...