![]()

CHAPTER ONE

What have we learned from studies with skilled adult readers?

In this introductory chapter, we discuss four aspects of written-word identification which play a crucial role in skilled reading: first, the effect of context in written-word identification; second, the automaticity of written-word identification (i.e., the written-word identification “reflex”); third, the time course of orthographic, phonological, and semantic code activation in written-word identification; fourth, the neural correlates of these processes.

This short overview of the literature breaks ground for an interpretation of reading as a highly specialized cognitive function. An emphasis on the automatic and autonomous nature of the written-word identification “reflex” in skilled reading defines the perspective that runs throughout the book and is essential to evaluating the theories and experimental findings that are presented here. Reading acquisition (chapter 2) and developmental dyslexia (chapter 3) are best understood when the focus is on written-word identification. In addition, a number of phenomena demonstrate the crucial importance of phonological factors in reading and suggest that dyslexia results from a phonological impairment (chapter 4). One critical issue is thus to understand how these factors enter into the word-reading “reflex” (chapter 5).

CONTEXT EFFECTS IN WRITTEN-WORD IDENTIFICATION

We know from reading expertise research that the seemingly effortless understanding of sentences or text is partly based on the automatic identification of written words. Such rapid and automatic word identification enables the skilled adult reader to recognize five words per second on average. This means that it only takes about a quarter of a second to recognize a written word from among the estimated 30,000 to 50,000 words in a reader’s mental lexicon. The automaticity of written-word identification by skilled readers results in processing that is relatively independent of processing at the sentence level and becomes increasingly autonomous as reading expertise develops.

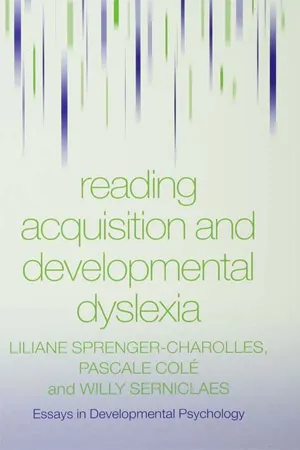

West and Stanovich (1978) demonstrated that, in skilled readers, sentence-context effects on written-word identification are not as strong because written-word identification occurs automatically. In their study, fourth and sixth graders as well as college students were asked to read target words (e.g., cat), as quickly as possible, in three conditions: (1) in a congruous sentence context with the prior display of a sentence context that was congruent with the target (e.g., the dog ran after the cat); (2) in an incongruous sentence context with the prior display of a sentence context that was incongruous with the target (e.g., the girl sat on the cat); (3) in a control condition with no sentence context but only the prior display of the word “the”. The results presented in Figure 1.1 show that congruous contexts reduced target-word reading time in all three groups of readers (although the effect was much weaker for skilled readers), while incongruous contexts slowed the fourth and sixth graders down, but did not affect the adults.

Raduege and Schwantes (1987) contributed another piece of evidence in favor of the increasing autonomy of written-word identification processes and the decreasing role of contextual facilitation as reading ability develops. Third and sixth graders were asked to read words in a neutral context, a congruous sentence context, and an incongruous sentence context. Half of the words were presented during a training phase, and the other half were not. The third graders’ results revealed a congruency facilitation effect of 120 ms on untrained words that dropped to as low as 47 ms on trained words. In contrast, for the sixth graders, there was no training effect (40 ms and 50 ms for trained and untrained words respectively). The latter finding suggests that written-word identification has become sufficiently automatic in sixth graders to prevent practice effects from occurring.

Figure 1.1. Mean word-reading time by school grade and context condition (adapted from West & Stanovich, 1978).

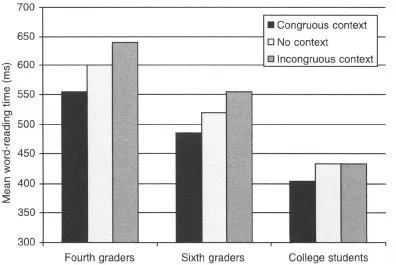

Some studies have also shown that heavy reliance on context is a defining trait, not only of beginning readers but also of individuals with more or less severe reading difficulties. For instance, in the study by Perfetti, Goldman, and Hogaboam (1979), skilled and less-skilled fifth graders were asked to read words presented either in isolation or in a story context. Figure 1.2 shows that the less-skilled readers made greater use of the written context than the good readers did.

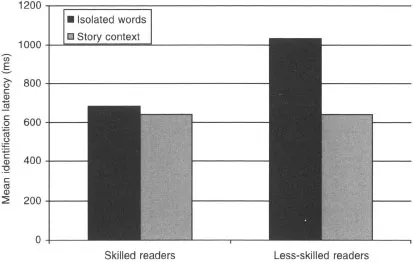

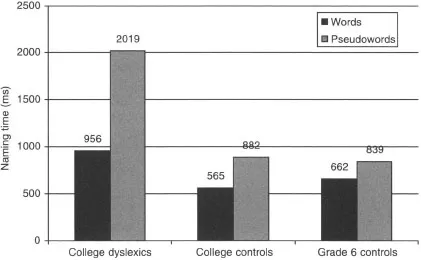

In a study by Bruck (1990), college students who had been diagnosed as dyslexic during childhood were compared on context use to an adult control group matched on chronological age and to a child control group matched on reading age (sixth graders). The three groups of subjects were asked to read words presented in a neutral context (e.g., “When I press the button, you will see the word ________”) and in a sentence context (e.g., “The English language treats pigs with ________ [contempt]”). Figure 1.3a shows that the dyslexic adults relied heavily on context, probably to compensate for their poor written-word identification skills, which were below the norm for their chronological age or reading age, as measured by a word and pseudoword naming test (Figure 1.3b). Reliance on context may explain why Bruck (1990) observed high standardized comprehension test scores in adult dyslexic readers.

Figure 1.2. Mean identification latency: words presented in isolation and in written story context for skilled and less-skilled fifth graders (adapted from Perfetti et al., 1979).

It thus seems that the role of context-based processing in written-word identification decreases as age and reading ability increases. More specifically, while sentence context can facilitate reading, the performance of more fluent readers seems to be dominated by rapid, automatic word identification. Such processes take place so fast that any effects arising from contextual factors – which take more time to process – are reduced. In less fluent readers, contextual and written-word identification processes occur at similar speeds, and both contribute to the performance levels observed. In fact, for skilled readers, facilitatory context effects disappear when the sentences used generate a meaningful but non-predictive context (Forster, 1981). This type of sentence predominates in everyday reading.

Figure 1.3(a). Mean reaction time to words presented in isolation and in context by reading ability, dyslexics and controls (adapted from Bruck, 1990).

Figure 1.3(b). Mean naming time to words and pseudowords by reading ability, dyslexics and controls (adapted from Bruck, 1990).

THE WRITTEN-WORD IDENTIFICATION “REFLEX”

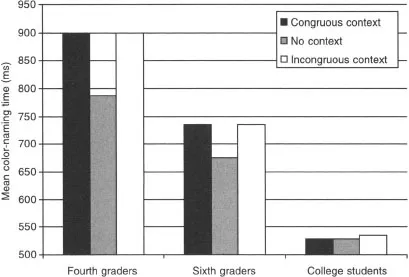

One of the essential properties of automatic written-word identification, beyond mere rapidity, is its involuntary nature – it takes place without the mobilization of attentional resources (Laberge & Samuels, 1974; Perfetti & Zhang, 1995). The Stroop effect (1935) is considered by many researchers as an indicator of automatic processes in reading. In the Stroop test, subjects must rapidly name the color of the ink in which a word is printed; the word presented may itself be the word for a different color. The Stroop effect provides information about the level of automaticity of written-word identification – the more automatic the processes involved, the less likely there is to be competition (and therefore interference) between the two color words activated (the written word presented, and the word for the ink color). West and Stanovich (1978) applied the Stroop test to sentences in order find out how “resistant” the automatic processes involved in written-word identification are to processing at the sentence level. They asked subjects to rapidly name the color of the ink used for one word in a sentence. The idea behind the combined use of context effects and Stroop effects is as follows: if the sentence context automatically primes a response other than the relevant color, then color-naming response time should be longer. However, if written-word identification processes automatically, the sentence context effect should be very reduced. Three context conditions were included: congruous, incongruous, and no context. Figure 1.4 illustrates the outcome: the context had a large effect on the color-naming times for fourth and sixth graders, but not for college students. The adults’ performance thus suggests that context no longer interacts with automatic word-identification processes.

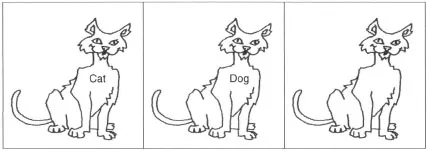

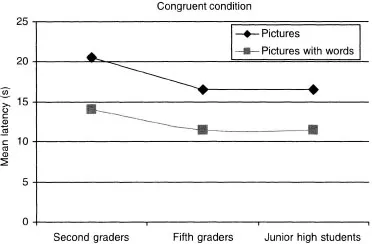

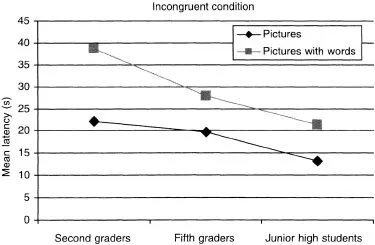

Ehri (1976) noted that even beginning readers processed printed words rapidly and automatically. She proposed a word interference task derived from the Stroop paradigm in which second graders, fifth graders, and junior high students were asked to name common objects and animals shown in labeled pictures. As illustrated in Figure 1.5a, the same drawing was presented with the correct label (congruous condition), an incorrect label (incongruous condition), or no label (control condition). The results, depicted in Figure 1.5b, indicated a congruency effect – response times to pictures with a congruous label were significantly faster than to pictures alone. Despite the subjects’ efforts to ignore the words, the magnitude of this effect was constant for younger and older readers. The results also indicated an interference effect – pictures with misleading labels took significantly longer to name than pictures with no label (see Figure 1.5c).

Figure 1.4. Mean color-naming time by school grade level and context condition (adapted from West & Stanovich, 1978).

Figure 1.5(a). Examples of the experimental conditions used by Ehri (1976).

Figure 1.5(b). Mean picture-naming latency by stimulus condition (picture only and picture with a congruous word) and school grade (adapted from Ehri, 1976).

Figure 1.5(c). Mean picture-naming latency by stimulus condition (picture only and picture with an incongruous word) and school grade (adapted from Ehri, 1976).

In Guttentag and Haith’s (1978) study, the interference effect reported by Ehri (1976) was found in first graders after only nine months of reading instruction. They suggested that the interference effects observed in their experiments and in Ehri’s were the result of semantic interference due to the rapid processing of the meaning of the printed word. Indeed, the interference effect was a function of the semantic difference between the picture and the word: it was greater when the picture and word belonged to the same semantic category (picture of a dog / word sheep) than when the two belonged to different categories (dog / notebook). These results were found by the end of first grade, but not earlier. Thus, the interference effect is related to age and reading ability – it is stronger for beginning readers than for more skilled readers, because of the greater automaticity of written-word identification in older subjects.

TIME COURSE OF ORTHOGRAPHIC, PHONOLOGICAL, AND SEMANTIC ACTIVATION IN WRITTEN-WORD IDENTIFICATION

The above results indicate that written-word processing is fairly automatic in skilled readers. It remains to be understood exactly what these readers access during written-word identification. Models of skilled reading (Coltheart, Rastle, Perry, Langdon, & Ziegel, 2001; Plaut, McClelland, Seidenberg, & Patterson, 1996) and beginning reading (Harm & Seidenberg, 1999) both describe word identification as resulting from the activation of three essential codes in the mental lexicon: orthographic, phonological, and semantic. The orthographic code of a word contains the letters that compose it and their combinations in words (e.g., t + r + a + i + n). The phonological code stores individual phonemes and their combinations (e.g., /t/ + /r/ + /ei/ + /n/). The semantic code includes the conceptual knowledge necessary for word understanding.

Research in this domain has brought out three main facts. First, the activation of these codes by skilled readers follows a precise time course: the orthographic code is activated earlier than the phonological code, and the semantic code is activated later (Ferrand & Grainger, 1992, 1993; Perea & Gotor, 1997). Second, skilled readers activate phonological codes earlier and more automatically than do less-skilled readers (Booth, Perfetti, & MacWhinney, 1999). Third, disabled readers – and more specifically dyslexic readers – have trouble activating the phonological codes of written words (Booth, Perfetti, MacWhinney, & Hunt, 2000).

The time course of orthographic and phonological code activation during written-word identification has been examined primarily by way of rapid masked priming, which makes it possible to study early automatic processes in written-word identification. In general, this procedure involves the presentation of a target word, on which the subject must accomplish a certain task (usually naming or lexical decision). The target word is preceded by the very quick presentation (50 ms, for example) of a prime word (or pseudoword), which may or may not share certain characteristics (orthographic or phonological) with the target. A mask composed of a series of hashmarks (#######) is displaye...