![]()

Part One

The Landscape of Child Care in the Post-Welfare Reform Era

![]()

Chapter One

Child-Care Arrangements and Help for Low-Income Families With Young Children: Evidence From the National Survey of America’s Families

Linda Giannarelli

Urban Institute, Washington, DC

Freya L. Sonenstein

The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

Matthew W. Stagner

Urban Institute, Washington, DC

Appropriate and affordable child care is crucial to the well-being of low-income families with young children. To understand the child-care issues these families face, it is important to examine the child-care arrangements they choose and the help they may receive in caring for their children. In this chapter, we present national and state data on the arrangements used by low-income families with young children and on their sources of help with child care. We examine differences by family structure, age of child, across states, and over time. For some issues, we compare low-income families with high-income families.

As we show, there is great diversity in the arrangements that low-income families use to care for their young children, and there is also great variation in how they get help with child care. Documenting this diversity provides an important backdrop for the consideration of policy and research issues. Recent and comprehensive information on these issues provides a context for policymakers and researchers hoping to understand how child-care policies may affect low-income people.

To examine these issues, we use data from the 1999 National Survey of America’s Families (NSAF) and compare some results to the 1997 NSAF. The NSAF is a key element of the Assessing the New Federalism (ANF)1 project at the Urban Institute. ANF is a multiyear project designed to analyze the devolution of responsibility for social programs from the federal government to the states, focusing primarily on health care, income security, employment and training programs, and social services such as child care.

The NSAF provides a comprehensive look at the well-being of adults and children at the national level and in 13 states studied in depth.2 It is a comprehensive source of information on how American families use child care, what they pay for care, and whether and how they get assistance. The survey is representative of the noninstitutionalized, civilian population of persons under age 65 in the nation as a whole and in the 13 states. Together these states are home to more than half the nation’s population. A “balance of nation” sample is added to provide unbiased national estimates. Through both the sampling procedures and the questions asked, the survey pays particular attention to low-income families.3 Interviews in 1999 were obtained from over 42, 000 households. The scope and design of the 1997 survey was similar, with over 44, 000 households interviewed.

The NSAF allows us to examine child-care arrangements at the child level. We describe the child-care arrangements made for children ages 0 through 4 while their primary caregivers (usually their mothers4) were employed. We compare the primary arrangements made by low-income parents (those with family income below 200% of the federal poverty level) to higher income families (those with family income above 200% of poverty). Further distinctions are drawn between the arrangements made by single-parent and two-parent low-income families.5 We also compare low-income families with a child under age 5 with those with no young children. Where we cite differences, they are statistically significant at the .10 level.

Information on whether and how families received help with child care was collected at the family level. Families were asked to report on the expenses for all children under 13 and were asked about various types of help they may have received for any child in the family. We present findings on the costs of child care for families, as well as the types and amount of help they receive. As with arrangements, we compare expenses and the sources of help for low-and high-income families with a youngest child age 5 or under with those with no children in this age group. As with arrangements, where we cite differences, they are statistically significant at the .10 level.

Child-Care Arrangements of Young Children from Low-Income Families

The NSAF gathers data on a variety of child-care arrangements for families with employed parents, including child-care centers, family child-care providers, relatives, and babysitters. Respondents discuss arrangements for “focal” children in two age groups (0–5 and 6–12).6 If a family has more than one child in an age group, the focal child for that age group is selected randomly. Some families use multiple arrangements for the same child. Primary arrangement means the arrangement used for the most hours while the mother worked. In those cases where the mother does not report a child-care arrangement for the focal child, we code the child to be in “parent/other” care. For preschool children, the “parent/other” category may include parents who watch their children while at work or parents who arrange their work schedules around each other. Because we ask only about care that was used consistently over the past month, this category may also include children who do not have a regular and consistent child-care setting.

Primary Arrangements of Low-Income Preschool Children

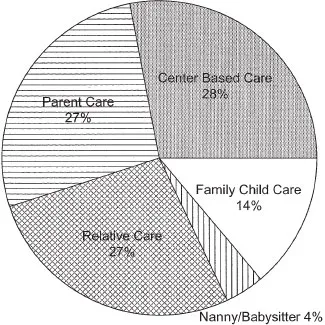

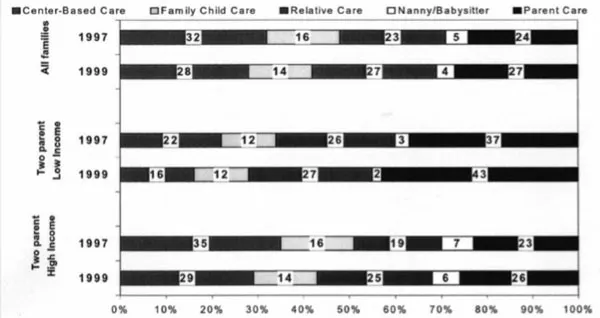

Figure 1.1 shows the distribution of primary child-care arrangements for children 0 to 4 years old with employed parents across all family types and incomes. The three most common forms of care are center-based care (28% of children), parent/other care (27%), and relative care (27%). Family child care is less common (14%), and use of a babysitter or nanny in the parent’s home is the least common form of care (4%). The type of care varies by family income, household structure (two-parent families vs. one-parent families), and age, as we examine later, and there is variation across states in the arrangements for young children from low-income families.

Fig. 1.1 Primary child-care arrangements of preschool children (0–4) with an employed parent, 1999.

Differences by Family Structure for Low-Income Families

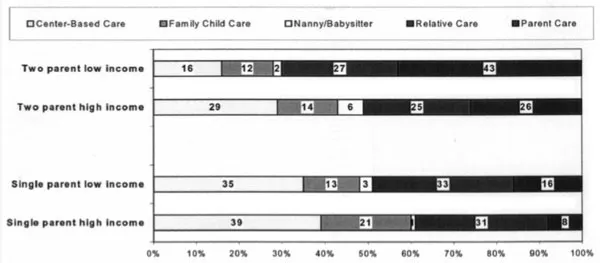

The types of child care children use vary greatly by family structure (see Fig. 1.2). Looking just at low-income families, center-based care is more common among children with single parents. Only 16% of two-parent low-income children are in center-based care, whereas 35% of children in low-income single-parent families are in such care. Parent/other care, in contrast, is most common among children in two-parent low-income families. Forty-three percent of children in two-parent low-income families are in this type of care, whereas only 8% of children in single-parent high-income families are in parent/other care. The low use of center-based care—and the high use of parent/other care—in two-parent low-income families may reflect the high cost of center-based care and the additional options available to families where two parents can share child-care responsibilities. The use of other types of care does not vary as greatly across family structure and income.

Fig. 1.2 Primary child-care arrangements of preschool children (0–5) with an employed parent by income and family structure, 1999.

Differences by Age of Child for Low-Income Families

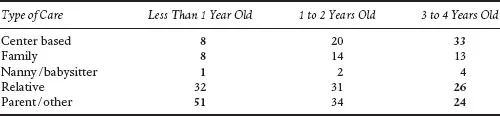

Care arrangements of children in low-income families differ by age of child, as shown in Table 1.1. Infants are significantly less likely than 1- to 4-year-olds to be in center-based or family child care. They are significantly more likely to be in parent/other care. Three- to 4-year-olds are significantly more likely to be in center-based care than children 0 through 2 years old and are significantly less likely to be in relative care or parent/other care.

Differences by State of Residence for Low-Income Families

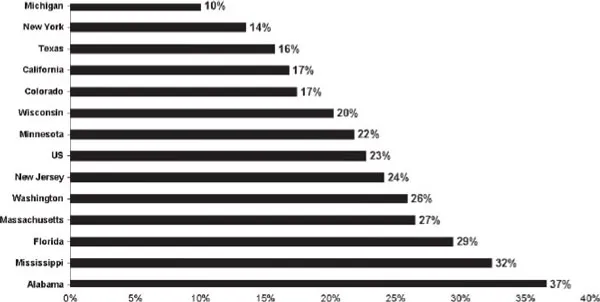

There are substantial differences among states in the types of care used for preschool children from low-income families. For example, differences are evident in the percentage of low-income children in center-based care (see Fig. 1.3). Twenty-three percent of low-income children were in center-based care nationwide in 1999. The proportion of low-income children in center-based care was significantly lower in Michigan (10%), New York (14%), and Texas (16%). It was significantly higher in Mississippi (32%) and Alabama (37%).

Changes Between 1997 and 1999 for Low-Income Families

Between 1997 and 1999, significant shifts occurred in the primary child-care arrangements made for low-income preschool children. We observe virtually no change between 1997 and 1999 in the pattern of arrangements for preschool children in low-income single-parent households. However, the primary arrangements among preschool children in low-income two-parent families shifted between 1997 and 1999 (see Fig. 1.4). Children in low-income two-parent families were significantly less likely to be in center-based care in 1999 than in 1997. Among these families, parent/other care increased significantly over the same period.

Table 1.1

Primary Child-Care Arrangements of Low-Income Preschool Children by Age of Child (1999)

Note. Bold indicates significantly different from other two age groups combined.

Fig. 1.3 Use of center-based care among preschool children (0–5) with a low-income employed parent by state, 1999.

Fig. 1.4 Primary child-care arrangements of preschool children with an employed parent, 1997 and 1999.

Table 1.2

Child-Care Expenses for Working Families with Children Under 13 Who Pay for Care by Whether They Get Help Paying (1999)

Child-Care Expenses and How Low-Income Families Get Help

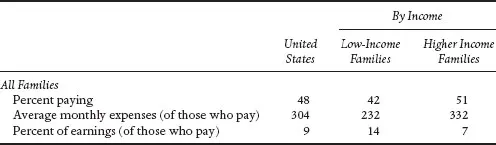

Child care is expensive, and it can eat up a large share of a family’s income. Some families bear this expense alone, but many receive help from relatives, government, other organizations, or employers.7 The NSAF data allow us to look at child-care expenses of families with employed parents who have children under 13 and to examine how these families receive help with child care. (The 1999 and 1997 NSAF data do not allow us to examine these issues for the subset of families with younger children.) Looking at all employed families with children under age 13, over 48% have some child-care expenses (see Table 1.2). Those who have expenses paid an average of $304 per month out of pocket in 1999, which was 9% of monthly earnings. Higher income families who pay for care paid, on average, $332 per month for child care, or 7% of their monthly income. Low-income families who pay for care paid, on average, about $100 less—$232 per month—which represented 14% of their monthly income.

Sources of Help for Low-Income Families

Given the large portion of monthly salary that low-income Americans pay for child care, it is important to see where they get help with child care. This analysis uses a broad definition of nontax child-care help, including free child care provided by relatives, subsidies from the government or other organizations, government programs such as Head Start and state-funded pre-kindergarten, and assistance from employers, nonresident parents, and other individuals. The estimates of help come from two sources. In most cases, mothers specifically reported a type of nontax child-care help that was coded as either government/organization help or help from an employer, nonresident parent, or other individual. However, in some cases, mothers did not explicitly report getting help, but apparently received some type of help because the family used nonparental child care without paying for it. For these families, we were able to infer the source of help based on the type of care the family used. Possible sources of such help include care by relatives who did not charge the family and programs that did not charge a fee, such as Head Start, state-funded pre-kindergarten, or fully subsidized care by a local institution.8

The 1997 and 1999 NSAF data underestimate the actual incidence of nontax child-care assistance. First, these data cannot identify cases in which a family pays part, but not all, of the child-care bill unless the respondent reports it. Respondents may not know they do not pay the entire bill, or they may not choose to admit to receiving such help. Also, it is impossible in the 1997 and 1999 NSAF to identify where a family pays for at least one child-care arrangement, but another is provided for free.9 For these reasons, we refer to the findings as minimum estimates of help being received.

In 1999, 29% of employed families10 with children under age 13 received some sort of assistance with child care, considering all types of help (except that provided through the tax code; see Table 1.3). The percentage getting help was higher for low-income families, at 39%. The most commonly reported forms of help were free provision of child care by a relative and help from a government agency or other organization. As Table 1.3 shows, a minimum of 16% of low-income families received free care provided by a relative. A minimum of 21% of low-income families received government or organizational help, which could include child-care subsidies through the Child Care and Development Fund (CCDF) block grant, child-care subsidies through other federal funds or through state programs, or help provided by private organizations. Few families reported receiving help from a nonresident parent, employer, or any other source.

Table 1.3

Percentage of Employed Families With Children Under 13 Using Different Forms of Help to Pay for Child Care by Income and Family Type, 1...