- 160 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frontiers of the Roman Empire

About this book

With its succinct analysis of the overriding issues and detailed case-studies based on the latest archaeological research, this social and economic study of Roman Imperial frontiers is essential reading.

Too often the frontier has been represented as a simple linear boundary. The reality, argues Dr Elton, was rather a fuzzy set of interlocking zones - political, military, judicial and financial.

After discussion of frontier theory and types of frontier, the author analyses the acquisition of an empire and the ways in which it was ruled. He addresses the vexed question of how to define the edges of provinces, and covers the relationship with allied kingdoms. Regional variation and different rates of change are seen as significant - as is illustrated by Civilis' revolt on the Rhine in AD 69. He uses another case-study - Dura-Europos - to exemplify the role of the army on the frontier, especially its relations with the population on both sides of the border. The central importance of trade is highlighted by special consideration of Palmyra.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Frontiers of the Roman Empire by Hugh Elton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

I

Introduction to Frontiers

Theory

As a historical subject, frontiers have attracted much attention and have generated extensive theory. One of the most famous of frontier theories is the ‘Turner thesis’, the creation of Frederick Jackson Turner, though it was never codified in such a form. Turner worked on the effect of the Western frontier on the democratic institutions of the United States, arguing that the lack of civil institutions on the frontier forced the development of individual rights and self-reliance.

Other studies of the American West have different emphases. In extremely crude terms, these theories can be synthesized into a colonial frontier characterized by the movement of settlers onto an under-exploited landscape, whose inhabitants are to be destroyed, so that the settlers can have farms. Turner’s frontier theories thus had nothing to say about the indigenous population, a feature which has drawn criticism from ancient historians.1

Another important frontier theorist, this time in Asian studies, is Owen Lattimore. He hypothesized three zones: a core, a transitional zone (= frontier) and the other (= barbarians).2 This framework is also used in core-periphery theory, as exemplified by Immanuel Wallerstein. His work deals with the creation of a world economy in the sixteenth century in an attempt to explain the dominance of Europe over other regions. Wallerstein’s model is explicitly built around one core, Europe, and the rest of the world is peripheral in varying stages. As he makes clear, this differs from the Roman Mediterranean in a number of ways. Though the Roman Empire is superficially similar, the ancient world cannot be safely viewed in capitalist economic terms, which is the driving force of Wallerstein’s arguments.3

None the less, this core-periphery model has been recently exploited by a number of ancient historians, both in conference papers and books. Of particular importance is Barry Cunliffe’s recent Greeks, Romans and Barbarians. However, the simple application of these models has been doubted by some, for example Greg Woolf, who suggests a need for further work. Other details of Lattimore’s theory, such as the existence of separate military, civil and economic zones, appear to have been overlooked.4

The Theory of Roman Frontiers

With the exception of the economic sphere, few such theories have emerged with respect to Roman frontiers. Most effort seems to have been devoted to the problems of‘frontier policy’, usually interpreted in terms of fortification placement. Aside from the military burden placed on the frontiers of the Empire, and the dire consequences should the defences tail, the social and economic problems are also important. The physical presence of most of the Roman army, a force of perhaps 400,000 men, in the frontier zones permanently altered economic patterns, in both manufacture and exchange. At the same time, a new social hierarchy was created, resulting in differences between Roman cities in the frontiers and in the hinterland. Justifying the study of the frontier is simple, producing a methodology more difficult.

To show the complexity, I will mention three points of view as to how the Roman frontier might work. The massive presence of the army cannot be ignored, and this has created the conventional interpretation. According to Hanson, ‘Roman frontiers were undeniably military in character; they were built and operated by the army and housed the troops who defended the empire against external threats.’ For Hanson, a frontier is explicitly military and he does not mention civilians, natives or barbarians.”5

Even when the people living beyond the Roman border are considered, it is often in simplistic terms. Most famously in this respect, Alföldi in 1952 wrote that ‘the frontier line was at the same time the line of demarcation between two fundamentally different realms of thought, whose moral codes did not extend beyond that boundary’. He argued that this moral boundary explained Roman atrocities and examined the difference in Roman activity on either side of the Danube.6

Thirdly, I recall a discussion after a paper at All Souls College, Oxford, in 1989, with Roger Batty and Malcolm Todd. The question was raised that, if one were dropped by parachute in the first century AD) into what is now Czechoslovakia, would one be able to tell if one was in the Roman Empire or not? The conclusion was that one probably couldn’t.

These three different interpretations of the same frontier systems are revealing in themselves. There is no contradiction between them, and this has allowed those concentrating on military architecture to co-exist with those focusing on cultural interchange. But accepting any one of these stances as a starting point will lead to different results from one’s work. Should one look at the frontier as a military affair, as a way of showing the differences between Roman and non Roman societies, or as an arbitrary line in the distribution pattern of cultural artefacts?

My response is to pick a way between all of them, and to attempt to discuss how life on the frontiers of the Roman Empire might have worked. This is a huge subject, and there is undoubtedly much relevant material that I have missed. None the less, I feel the attempt is worth making.

Concepts of Frontiers

Modern borders are usually represented on maps by a single line, often red or dotted, providing a break between one administrative body and another. In Britain, county boundaries have been the delimiters for police work, parishes, and thus registration of births, marriages and deaths, county councils and their services and parliamentary seats. In the United States the situation is similar, though individual states set their own income and sales taxes, have independent armies (in the form of the National Guard), state prisons, car licensing and road regulations. These activities are administered by the county or state government and their competence ceases beyond the border, which is the same for all areas of responsibility.7

Not all activities are circumscribed by these borders. Trade and business carried out freely across local government borders, though different jurisdictional units may have different regulations on, for example, when alcohol may be sold. The provision of a common currency allows goods to be bought and sold anywhere within the boundaries of the nation. Regulations seldom determine whether individuals must work in the same boundary area in which they live. Though local police competence is limited by these boundaries, they can, in appropriate circumstances, act across such. Borders between modern nations are administered in a more rigid fashion. Across the border, laws, institutions and currencies are usually different, documentation is often required for crossing and certain goods may not be sold if they do not meet the standards of the importing country.

This mental framework is often applied to historical frontiers, but the collocation of government functions on the same borders need not be considered normal. In a paper on eighteenth-century France, Sahlins cites a committee report from 1790:

The kingdom is divided into as many different divisions as there are diverse kinds of regimes and powers: into diocèses as concerns ecclesiastical affairs; into governements as concerns the military; into généralités as concerns administrative matters; and into bailliages as, concerns the judiciary.8

Here we see the state’s administrative zones divided by types of government, rather different from a modern state. Furthermore, modern political boundaries do not affect all facets of life. Language is not the prerogative of any particular nation and often crosses boundaries. Moreover, it allows links between communities, particularly where the border has been moved in recent history. Religion also achieves the same links, while recent events in eastern Europe show that people’s definitions of their own ethnicity often clash with the desires of their governing body. Enclaves of Bosnian Muslims and Bosnian Serbs clearly demonstrate the problems in creating viable political boundaries.

How should the Roman world be seen? In the Roman Empire, as in the unfortunate case of the region which was once Yugoslavia, political, social, ethnic, religious, linguistic, economic and military boundaries all overlapped. This is the perspective that I wish to use throughout this book, the concept of a frontier, not as a line or simple zone, but as a series of overlapping zones.

Such a fluid frontier concept is not always easily accepted, and many Roman historians seem to want a preclusive border, with a clear definition as to what was Roman and what was barbarian. Thus Willems wrote in 1983, with reference to north Gaul in the fourth century, ‘it seems we will have to live with an essentially “fuzzy” zone in which, because of the decreasing imperial control and the growing number of Frankish settlers from across the frontier, a new regional structure was already developing’.9 Although forced to recognize that there was no clear boundary in the late Empire, he clearly feels unhappy with this and probably has in mind a strong correlation between a non-‘fuzzv’ zone and effective imperial control. Similarly, Okun in 1989 was able to write ‘because of the geographical limits of frontiers, which are identifiable and distinguishable, and their clearly deliminated [sic] temporal limits, frontiers are circumscribed units of study’.10 Although she concentrates on military frontiers, she rejects Whittaker’s model of frontiers dividing homogenous economic groups, and consequently studies only the Roman bank of the upper Rhine, rarely venturing across it.

This modern concentration on well-defined borders has its counterpart in ancient writers. Rivers were accepted as borders between the Romans and another state or between Roman regions. In particular, the Euphrates was often a symbol of the limits of Roman and Parthian power (though Strabo does comment that it was a poor boundary), while the Rhine and Danube were often also seen as border markers in Europe. There seems to have been no official nature to these characterizations, but they reflect what many felt about political borders. Mountains seem to have had a lesser presence as such markers, probably because they were found less often on the fringes of the Empire, though they were widely seen as internal delimiters.”11

Geography, however, was always overshadowed by politics and even such obvious boundaries as the Bosphorus, dividing Europe from Asia, could be ignored. The city of Byzantium in the early second century was part of the province of Bithynia on the other side of the Bosphorus and we have a record of the Bithynian governor Pliny the Younger inspecting the city’s accounts. This was the result of lands owned by the city around Lake Dascylitis in Bithynia.12 With such situations as this existing, it is not surprising that many modern historians have become more receptive to the problems of boundaries and their definition. Millar has shown an unhappiness with the idea of fixed borders: ‘Where the “borders”, if that indeed is the right term, of the Nabataean kingdom, Herod’s kingdom and the provincial territory lay at successive stages in the later first century is often very obscure.’13

Types of Roman Frontier

In the Roman world there were a number of overlapping frontier zones. These frontier zones might be defined by four groups of people: Roman soldiers, Roman civilians, local natives and barbarians. Each group had their own boundaries of different types: political, social, ethnic, religious, linguistic, economic and military. These could, but did not have to, coincide with those of other groups. It was this mixture of boundaries which together made the frontier.

These converging zones are well illustrated in the case of Antoninus, a Roman soldier who deserted to the Persians in 359. His story is retold by Ammianus Marcellinus, who served as an army staff officer in the east at this time. Antoninus was a rich merchant who joined the staff of the governor of Mesopotamia. For unspecified reasons he fell into debt to certain powerful men and was unable to repay the money he owed. Therefore the debt was transferred to the imperial treasury. Antoninus promised to pay, but at the same time decided to desert to the Persians. He used his military rank to gather as much information about the Roman army in the east as possible, information of particular value since the Romans knew that the Persian King Sapor II (309–79) was preparing to go to war with the Romans. Antoninus then bought a farm at Iaspis on the Tigris. Since he owned this property, his creditors were not concerned that he was on the fringes of imperial authority or that he was accompanied by his family and household. Once here, Antoninus negotiated with Tamsapor, the Persian frontier commander, whom he had previously met, and finally ferried his family and household across the Tigris to the Persians. Once in the Persian Empire, he was taken to the Persian court and acted as an adviser to Sapor, making use of his extensive knowledge of the region to guide the Persian attack.

Antoninus’ exploits thus demonstrate the mixing of several different types of frontiers. It was probably his career as a merchant which had led him to the acquaintance of Tamsapor, while it was his military experience which made him so valuable to the Persians. Antoninus was forced to use care to cross the border, since there were troops stationed there. Once across the border, he was immune from Roman legal action, and it was his personal financial problems as a civilian which caused his flight in the first place. He certainly knew the region well, probably as a result of his military service. In any case, his purchase of property on the banks of the Tigris was not viewed as abnormal by any means while the apparent ease of communication across the Tigris suggests that this was not a physical barrier. Lastly, Antoninus seems to have fitted in well at the Persian court. He played a part in the debates of the Persians, because Greek was used at the Sassanid court, allowing Antoninus to talk to Sapor without an interpreter.14

Antoninus’ story thus shows a number of ways of approaching the frontier. Traditionally, the study of Roman frontiers has been concerned with the Roman army and its fortifications. Since most of the army was stationed in the frontier zone, there is a strong justification for this point of view. However, the role of the army on the frontiers is a large and complex topic, in part because there were a number of differing objectives which the army tried to achieve. By defining these, it is possible to see how they affected the concept of a frontier.

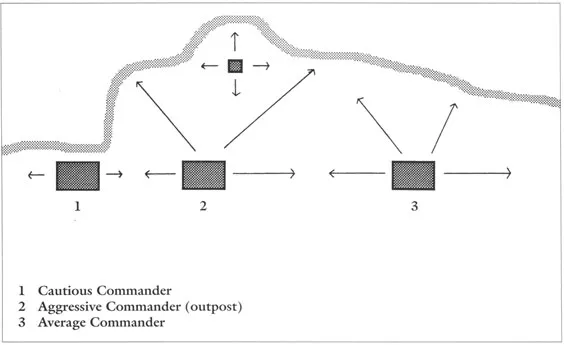

The most important objective was to maintain imperial security. Enemies could be defeated within their own territory or if they tried to enter Roman territory. If it was accepted that all attacks would be dealt with at the moment they entered Roman territory, then there could be a single military border. However, it was preferable that attacks would be defeated beyond the borders of the Empire. This acceptance of military action beyond the territory of the Empire led to the creation of a military frontier which was different from that of occupation or garrison, a frontier of intervention (fig. 1). Since the actions of the garrison were not determined by the positions of their fortifications, too close an association between defence policy (‘frontier policy’) and the physical location of forts should not be assumed.

Fig 1 intervention frontiers: a model

This intervention frontier can be seen on two levels: that oflocal intervention, which a commander could carry...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Preface

- Chapter I: Introduction To Frontiers

- Chapter II: The Establishment Of The Roman Frontier

- Chapter III: Allied Kingdoms And Beyond

- Chapter IV: The Consolidation Of The Rhine Frontier

- Chapter V: The Army On The Frontier

- Chapter VI: Commercial Activity

- Chapter VII: Across The Border

- Conclusion

- Appendix: The Stobi Papyrus

- Abbreviations

- Reference

- Bibliography

- Index