eBook - ePub

Street Sex Workers' Discourse

Realizing Material Change Through Agential Choice

- 240 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Incorporating the voices and insights of street sex workers through personal interviews, this monograph argues that the material conditions of many street workers — the physical environments they live in and their effects on the workers' bodies, identities, and spirits — are represented, reproduced, and entrenched in the language surrounding their work. As an ethnographic case study of a local system that can be extrapolated to other subcultures and the construction of identities, this book disrupts some of the more prevalent academic and lay understandings about street prostitution by providing a thorough analysis of the material conditions surrounding street work and their connection to discourse. McCracken offers an explanation of how constructions can be made differently in order to achieve representations that are generated by the marginalized populations themselves, while placing responsibility for this marginalization on the society in which these people live.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Street Sex Workers' Discourse by Jill McCracken in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Sexualidad humana en psicología. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Ciencias socialesSubtopic

Sexualidad humana en psicología1

Quotidian Rhetoric Creates Meaning through Collage

Language is fluid. It both shapes and reflects changes in society and local communities. Discourse is made up of ideologies and ethical systems held by the users of that language and their communities that create and continue to cultivate the language. As Norman Fairclough argues in Discourse and Social Change:

Discourses do not just reflect or represent social entities and relations, they construct or “constitute” them; different discourses constitute key entities […] in different ways, and position people in different ways as social subjects […] and it is these social effects of discourse that are focused upon in discourse analysis. (p. 3–4)

These ideological belief systems affect people’s lives. The language used to describe a person who exchanges sex for economic gain can embody different ideologies. For example, consider the words whore, prostitute, sex worker, sacred prostitute, or new age priestess. Each word conveys different values, and therefore interrogating the ideologies and ethical systems found in these concepts allows the reader to better understand how these identities are created and can perhaps be created differently.

My analysis draws on both rhetorical—the study of how language shapes and is shaped by cultures, institutions, and the individuals within them—and ideological—the identification and examination of the underlying belief systems contained within the language. Both language and the underlying belief systems contained within the language are examined. I draw on communication studies Professor Barry Brummett’s concept of quotidian rhetoric as a foundation of my analysis of street-based sex work. Brummett (1991) defines quotidian rhetoric in Rhetorical Dimensions of Popular Culture as:

the public and personal meanings that affect everyday, even minute-to-minute decisions. This level of rhetoric is where decisions are guided that do not take the form of peak crises […] but do involve long-term concerns as well as the momentary choices that people must make to get through the day. […] People are constantly surrounded by signs that influence them, or signs that they use to influence others, in ongoing, mundane, and nonexigent yet important ways. (p. 41)

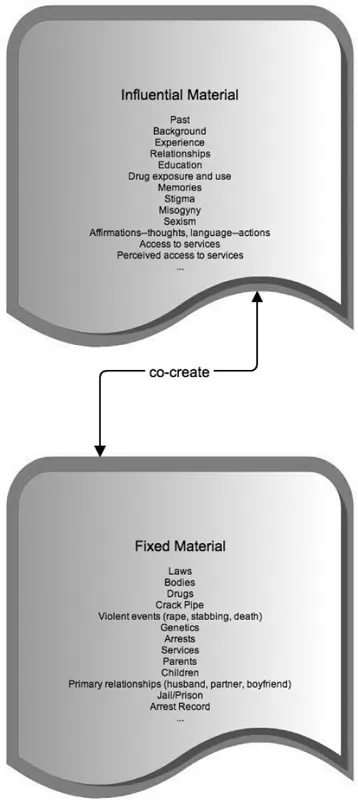

Brummett argues quotidian rhetoric is carried out through appropriational manifestations of rhetoric, or what is most appropriate in a given situation. Therefore people, in general, are relatively “less consciously aware that the management of shared meanings is underway,” which means they are “less likely to take or assign responsibility for a rhetorical effort” (emphasis in original, p. 42). Because appropriational rhetoric is participation in as much as it is the production of the management of meaning, ultimately, individual responsibility for both is less defined. Ideologies as well as material reality are both fixed and continually changing based on both external and internal events. I use the terms fixed material and influential material to better understand the materiality of my participants’ language and lives, as well as the material conditions that co-create their lives. After presenting this theory, I apply it to the constructions of problems and solutions surrounding street-based sex work as well as the material conditions of street-based sex work.

The concepts fixed material and influential material identify the malle-ability and changeability of material conditions. In other words, the level of embedded materiality in an object or concept influences how material can change. By fixed material, I mean this object, or material, is fixed for the moment and therefore has a momentary permanence, which does not imply that fixed material cannot be changed. For example, a house, a law, and even a person, would be considered fixed material—a concrete reality currently in existence. Influential material describes how conditions, objects, and circumstances impact fixed material—the thoughts, actions, words, and events that influence actions and fixed material conditions. The influential material is more fluid than the fixed material, and, in some cases, more pervasive.

An example is the wooden, kitchen table at which I sit. It is fixed material, although it is not permanent. Rather, I could, with influential material (my thoughts, ideas, conversations with others) and tools (fixed material), choose to chop it up into pieces, sand it down into dust, or burn it. I could also turn it upside down and make it into a piece of art. There are myriad options for fixed material based on the choices, options, perspectives, and influences available. And yet to illustrate the power of the influential material, the table is continuously defined by a culture that uses and understands tables. If this table were transported to a place where there is no word for table, or there are no objects used as tables, this fixed material would no longer be understood as a “table” and perhaps would take on a different purpose or be changed into something more usable and understandable within that culture. This fixed material would then embody other uses and purposes beyond that which was initially intended in its creation, allowing it to be a different fixed material subject to other influences, goals, uses, and perhaps changes.

Influential material is continually moving toward and away from “fixedness” and is less concrete than fixed material. It may be fixed in its own right, as a thought can have a momentary permanence and therefore be fixed, and yet it is less fixed than an action. Therefore, my stepping on a bug would be a fixed material action and would have very specific fixed material consequences for the bug’s life, or lack thereof because of my action, as opposed to my influential material thought of thinking about stepping on the bug, which does not actually impact the bug’s life (or mine as well) until I make a fixed action to step on the bug or walk away. A final example, the existence of a crack pipe is more fully embedded materially than, say, a participant who says she thinks about using crack. Both are products of material conditions and work to create other actions and realities, and yet one is more concrete than the other. Within a system of fixed and influential material, the influential is less tangible. In this example, the existence of a crack pipe on one’s person could lead to arrest, whereas the thought of smoking crack would not.

The fixed materiality, likewise, impacts the influential material. For example, the law against exchanging sex for money in Nemez is a fixed material condition. It is subject to change, but at the time of the interviews and through the writing of this book, exchanging sex is illegal. An observer may feel pity, outrage, satisfaction, surprise, or fear upon viewing the arrest of someone for prostitution, and this response or description of their response would be considered an influential material condition. This response could, combined with multiple other actions and influences, create a fixed material condition of a petition to change the law, a petition to enforce more arrests, or the movement of a person from that location to avoid arrest. Because the movement from fixed to influential is not always easily defined, many material conditions can be defined according to both. For example, one’s past could be considered both fixed and influential because it has occurred and can continue to influence the individual in different ways depending on present circumstances, intent, etc.

These categories do not clearly demarcate the concepts because nothing is ever entirely fixed or influential, and yet these terms offer a way of understanding the material conditions of street-based sex work and the ways these conditions might be disrupted. There are aspects more fixed and those more malleable and mutable. To complicate matters further, the level of material embeddedness does not progress respectively from influential to fixed. In other words, just because something is defined as influential, it is not necessarily more easily changed than that which is fixed. Take for example the material of a law and a belief—specifically, the law (fixed material) that makes prostitution illegal and the belief (influential material) “prostitutes are immoral”. It may be far easier to change a law than a belief.

The above influential and fixed material conditions interact amongst and between each other to further entrench or concretize certain conditions. Most examples reside in both categories because although many incidents are fixed—like one’s past, arrest record, or drug use, and therefore influence one’s material reality in the present—these events or circumstances do not solely dictate one’s future.

Figure 1.1 Influential and fixed material.

Through this analysis, I examine the discursive and material conditions understood and continually recreated that gain the density of fixed material or matter such that their constitution is no longer questioned. Take for instance the term prostitute, which has become fixed as an entity, construct, and identity in the past two hundred years (Karras 1996; Lerner 1986; Otis 1985). What is lost when this term becomes fixed material and is used to identify certain people in certain contexts? What can happen when the constitution of this term and action is questioned, as well as the related material conditions or commonly understood “problems” surrounding the exchange of sex for money? And finally, how do fixed and influential material influence and constrain each other? And what are the implications of these constraints for individuals who participate in these exchanges and the society in which they live?

The goal is not to discern whether something resides solely as fixed or influential material, but rather to use these terms as an heuristic that reveals how material conditions can stagnate, change, fluctuate, and be disrupted based on one’s understanding of these fixed and influential materials as well as the influence they have on one’s ability to act as an agent and influence material conditions and systems. English Professor Beverly Moss (2011) argues “we must expand the spaces and sites in which we examine these practices [literate activity and behavior]” (p. 2). Although Moss focuses on the written word, my goals align with hers in exploring how “the material, social, and cultural conditions in which they operate define the range of agency” (p. 5). Multiple discourses, ideologies, and perspectives influence the local media, the discourse used in social service and enforcement agencies, and in the language of the people I interviewed. Brummett (1991) refers to this blending of rhetorical transactions as “a complex of mosaics created within a certain time frame” (p. 70).1 Brummett argues an individual orders her world by constructing patterns, or mosaics, that make their experience meaningful while at the same time creating herself as a subject who is positioned by the pattern (p. 84). Therefore, ideology, or the mosaic, is constructed by the individual in a way that makes her known experience meaningful, while it also constructs the individual as a subject who is recognizable within that same pattern. Examining and deconstructing these mosaics is a way of better understanding the underlying belief systems or patterns of experience that “make sense”—to an individual or individuals—while revealing how their own positions are created and reflected by that same belief system or pattern. This mosaic creation is a process of managing meaning.

I play with vision as a way to show how one’s experiences, beliefs, history, and the available information influence one’s perception of events, circumstances, and individuals.

Figure 1.2 Duck-Rabbit ambiguous image.

Like the duck and rabbit image in Figure 1.2, how one views the lines drawn influences the overall picture. It is possible to see both at once, or to switch back and forth between two entirely different images. The truth does not lie within the “lines” so to speak, nor the image of the duck or rabbit, but rather “truth” is created in the moment. Ultimately, one creates a collage of understanding.

Some collages create more dominant patterns than others. And a variety of collages make up an individual’s and society’s viewpoints about the exchange of sex for money or other gain based on one’s experiences, history, and the patterns that emerge based on these contexts in media, events, and personal circumstances. As the mosaic is a fixed entity, the kaleido-scope image is a more malleable way of understanding how patterns are created and can shift and change based on external elements as well as the agency and perspective of the viewer. As a viewer reads the patterns, she can also change the theme with a slight shift. The kaleidoscope represents the mutable nature of our readings of texts and patterns of experience while simultaneously reflecting the fixed notions of terms and ideas. Although they can be altered, or may change, each picture bears some of the same ideas embedded in the previous scene. English Professor Jacquelyn Jones Royster introduces the “kaleidoscopic view” as a way

rhetorical action becomes visible as a site of continuous struggle in response to an ongoing hermeneutic problem [ . . . and] is designed to make the hidden and unrecognized visible. This view, by its very framing (that is, in being multi-lensed), encourages us, above all else, to complicate our thinking, rather than simplify it, in search of greater clarity and also greater interpretive power. (p. 73)

Using a “material kaleidoscope,” so to speak, both the viewer and the view shifts: the viewer is an active participant in the process.

Do “Prostitute” Bodies Matter?

Drawing on Rhetoric and Comparative Literature Professor Judith Butler, I use the word matter as a noun (the material body) and a verb (the importance of certain bodies) in order to explore both in specific contexts. In Bodies that Matter, Judith Butler (2011) asks “Can language simply refer to materiality, or is language also the very condition under which materiality may be said to appear?” (p. 6). Drawing on Butler’s argument that language is a condition under and through which materiality appears, within this study I apply this same question to the concept, construction, and reality of the prostitute. For example, Butler’s “sex of materiality” is a site where she traces materiality as “the site at which a certain drama of sexual difference plays out” (p. 22). As Butler emphasizes, “to invoke matter is to invoke a sedimented history of sexual hierarchy and sexual erasures.” The “prostitute” is also a site at which differences—morality, identification, belief systems, actions, and their implications—play out. What is gained and lost in the assumptions and beliefs embodied and materialized in the “prostitute” concept? Butler asks these questions about which bodies are said to “matter” in terms of importance and, I would add, as agents active in shaping their own lives. As Butler argues:

It must be possible to concede and affirm an array of “materialities” that pertain to the body, that which is signified by the domains of biology, anatomy, physiology, hormonal and chemical composition, illness, age, weight, metabolism, life and death. None of this can be denied. […] That each of those categories have a history and a historicity, that each of them is constituted through the boundary lines that distinguish them, and hence, by what they exclude, that relations of discourse and power produce hierarchies and overlappings among them and challenge those boundaries, implies that these are both persistent and contested regions. […] We might want to claim that what persists within these contested domains is the “materiality” of the body. (2011, p. 36)

Butler clarifies this idea of repetition as enabling or constructing the subject: “for construction is neither a subject nor its act, but a process of reiteration by which both ‘subjects’ and ‘acts’ come to appear at all. There is no power that acts, but only a reiterated acting that is power in its persistence and instability” (p. xviii). She asks for a return to the idea of matter, “not as site or surface, but as a process of materialization that stabilizes over time to produce the effect of boundary, fixity, and surface we call matter (emphasis in original, p. xviii).

If materialities are “both persistent and contested regions,” there is space through which the materialities can be and are made differently. Focusing on and integrating the voices of the women who inhabit these material bodies and their lived material conditions create opportunities not only for those who do not inhabit these bodies in the exact same way to understand, but also to change these materialities through altered perceptions and understandings. Simultaneously, I examine the “prostitute” concept based on Butler’s exploration of what is represented and produced as “outside” oppositional discourse. Butler argues:

The task is to refigure this necessary “outside” as a future horizon, one in which the violence of exclusion is perpetually in the process of being overcome. But of equal importance is the preservation of the outside, the site where discourse meets its limits, where the opacity of what is not included in a given regime of truth acts as a disruptive site of linguistic impropriety and unrepresentability, illuminating the violent and contingent boundaries of that normative regime precisely through the inability of that regime to represent that which might pose a fundamental threat to its continuity.” (p. 25)

In other words, using this theory as a framework, I explore how the idea, term, identity, and material reality of “the prostitute” is constituted in the discourse surrounding women who exchange sex for money or other gain, and then, as the places for disruption are revealed, explore how materialities can be made differently.

What does the term prostitute constitute and label? How does the “outsider status,” in terms of outside mainstream behaviors and identities, of the “prostitut...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Figures

- Note on the Transcriptions

- Preface: Telling Our Stories about Street-Based Sex Work

- Acknowledgments

- 1. Quotidian Rhetoric Creates Meaning through Collage

- 2. Who is the Victim: The Neighborhood or the Woman?

- 3. Is She a Criminal, a Victim, or a Victim of the Criminal Justice System?

- 4. “An Opportunity to Change”: Responsibility and Choice

- 5. Systemic Violence Perpetuates Victim Status

- 6. Creating Agential Choice from Cages of Oppression

- Appendix A: Participants

- Appendix B: Research Process and Layers of Data

- Appendix C: Number of Times Terms Included in Newspaper and Participant Interviews Corpora

- Appendix D: Interview Materials

- Notes

- References

- Index