![]()

The Conservation of Natural and Cultural Heritage in Europe and the Mediterranean: A Gordian Knot?

Giorgos Catsadorakis

Defining ‘Conservation’, ‘Natural Heritage’ and ‘Cultural Heritage’

Everyone, from laymen and activists to politicians and scientists, seems intuitively to understand and agree with a statement such as: ‘The natural and cultural heritage (of a site) must be conserved’. As obvious and routine as this may be, if one wishes to go a step forward and implement specific actions, major problems emerge in adequately defining—particularly operationally—all three main terms: ‘conservation’, ‘natural heritage’ and ‘cultural heritage’, although they all sound familiar, are firmly established and widely used. It is beyond the scope of this paper to explore the content of these terms or to review the vast relevant literature. In order to serve my aim, however, some important points must be mentioned.

(1) We cannot exactly define what conservation means in practical terms because the subjects of conservation are continually changing and because deciding what exactly we want to conserve is not a purely scientific matter, so it can never have unequivocal, objective answers.1 If we want to conserve a ‘natural’ or ‘pristine’ situation, the answer is that there is no rational scientific basis on which to define ‘natural’2 and since ecosystems with or without human interference change continually, there is no pristine situation. The science of conservation biology may inform the whole process of conservation activities, but decisions on what to conserve are arbitrary and mainly a matter of science, values, expediencies and politics. The best approximation to a definition of conservation is ‘creating conditions that allow ecosystems to change, with the least species loss and the least damage to ecosystem processes’.3 This is not very helpful, however, in decision making on what, how much, when and for how long.4 Generally, conservation entails both site protection and site management and should be conceived along four main axes: genes, species, habitats, landscapes. Unfortunately so far, only species and habitats have received sufficient attention from the international community.

(2) Natural heritage must necessarily relate to a specific place and time period and should at least include: specific sites, types of landscapes, species (and genes in the form of sub-species, races, varieties) and habitats. As ecosystems change continuously and as the human impact upon them also varies, natural heritage has a continuously changing content too. Since it is defined always in relation to the past (and present), the natural heritage of a place is also contingent upon the extent of our knowledge of past situations. For example, the natural heritage of the classic land of Attica, Greece, today is not like that of 500 years ago and certainly not like that of 5,000 years ago. The knowledge, however, we possess about the nature of Attica at that time is meagre. So the benchmark situation to be used to represent the natural heritage of Attica remains unresolved.

(3) Cultural heritage is composed of tangible and intangible elements.5 The latter include language, legends, myths, norms, perceptions, practices, habits, customs, diets, methods, etc. Problems similar to those in (2) above also pertain to the notion of cultural heritage, which is itself a continuously changing concept, with much quicker rates of change than natural ecosystems, sometimes occurring in leaps.

Thus, to move forward in a concrete and useful manner we must inevitably compromise and accept a large amount of vagueness. Because the necessities to preserve our natural and cultural heritage are real and pressing, we must manage to achieve our goals despite this paradox.

The Spatial Dimension: The Mediterranean in Europe

The Mediterranean basin is probably the most difficult region to overview, because of its geological, biological and geopolitical diversity.6 There are not always enough statistics for the northern part of the basin, which is a part of Europe, but the main features of the Mediterranean are described here, referring mostly to its northern coast and whenever necessary to the entire basin. Generally, whatever refers to Europe also holds true for the Mediterranean. In general terms, what sets the Mediterranean apart, or simply at the other end of the continuum, is its much higher biodiversity, a greater variety of landscapes and management practices,7 and a resulting higher cultural diversity; above all, it shows an intricate patchwork of habitats with a far finer grain (smaller average patch size) than the rest of Europe. This results from its more intense relief, its more varied geological history, the mosaic of local climates, the relatively diverse effect of the glaciations and, of course, the fact that it is the cradle of very ancient civilisations, it is more or less densely populated and it has been heavily influenced by humans for at least 10,000 years.

In his worldwide analysis of biodiversity, Myers8 rates the Mediterranean basin as one of the world’s 18 hotspots. However, the basin is far too extensive and heterogeneous to be treated as a single hotspot area.9 The Mediterranean is one of the world’s major centres for plant diversity, where 10% of the world’s higher plants can be found in an area representing only 1.6% of the Earth’s surface.10 Also, as many as 366 bird species currently breed in the 3 million km2 of the Mediterranean basin, compared to the 490 breeding in the 10 million km2 of the whole of Europe.11 It also includes 45% of the bovid varieties and 55% of the goat varieties of Europe and the Middle East.12

On the other hand there is growing local demand for tertiary activities, especially near the coast, from promoters, speculators and entrepreneurs of all sorts. So, a dichotomy exists throughout the basin; far from the coast there is abandonment and woodland encroachment while along the coast all contact with the ecological and cultural past of the Mediterranean is being lost.13 Yet the Mediterranean is still the number one tourist destination in the world, currently drawing more than 30% of annual tourist trade mainly from countries of northern Europe.14 The Mediterranean also includes most of the areas of priority for conservation in Europe, since these are subject to rapid loss under current policies.15 Hereinafter, by ‘Mediterranean’ I refer only to northern Mediterranean countries and especially those belonging to the EU.

In Europe, and Particularly in the Mediterranean, Natural Heritage Cannot be Conceived Separately from Cultural Heritage

After 10 000 years or more of ‘co- habitation’ most Mediterranean ecosystems are so inextricably linked to human interventions that the future of biological diversity cannot be disconnected from that of human affairs.16

There are hardly any places on earth that do not bear the traces of human influence, and the few cases have certainly been the exception for hundreds of years. In Europe every place, with the possible local exceptions of steep cliffs and the highest mountain tops, is culturally modified.17 It is fully documented and widely accepted that most of Europe consists of cultural landscapes. Farming accounts for more than 60% of the land surface of the EU, though less than 10% in Fennoscandia where forests predominate.18 In the Mediterranean, half the land is occupied by agriculture and the rest by forests, mattorals and range lands19 while the statistics are certainly confusing in cases where both farmland and shrubland are used for grazing. Agriculture and livestock rearing is also the major land use inside most of the protected areas in Europe.20 This situation is similar but even more pronounced in Mediterranean countries as a result of a longer human presence. In fact some scientists have talked about a complex ‘co-evolution’ that has shaped the interactions between Mediterranean ecosystems and humans.21

Throughout Europe many people still suffer from the misconception that most areas important for nature conservation are wilderness areas. In fact, much of what is of value throughout Europe is not wilderness but farmland.22 The majority of the 20,000 protected areas presently existing in Europe are also dominated by cultural landscapes.23

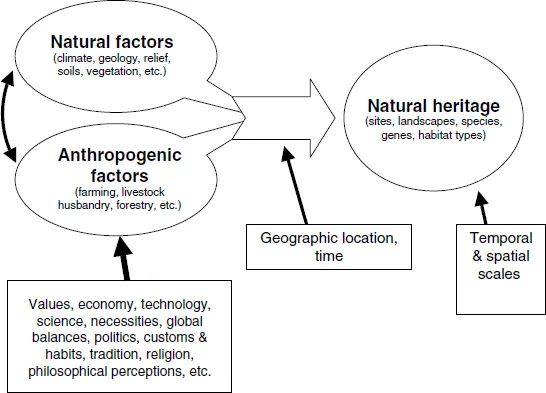

It is now well understood that the present situation of the natural environment of Europe is not a product of eons of natural processes alone but also of centuries of farming, livestock rearing, forestry and other kinds of management by humans. Figure 1 makes clear that, whatever the exact meaning of the terms ‘conservation’ or ‘natural heritage’, in order to conserve the natural heritage of Europe, either within or outside protected areas, we have to manage in an appropriate way the anthropogenic factors (i.e. mainly farming and forestry) that contribute to the creation of this heritage, since our potential to affect actively the natural factors is considered negligible and will not be discussed any further. Additionally, it is emphasised that there is no practical alternative, other than through farming, livestock rearing and forestry to sustain those landscapes, habitats and wildlife communities that are valued as our natural heritage.24 The human element cannot be divorced from nature conservation issues in the European countryside.25

Of course, the proper management of human activities may entail that in certain, generally few, cases the best solution for the protection of particular natural heritage elements would be totally to exclude human presence, in which case we are talking about site ‘protection’. Especially in the densely-populated Mediterranean, absolute exclusion of humans from very small areas will always be important to avert overdisturbance, but this cannot be the principal conservation strategy.

Figure 1 Schematic representation of the relationship between natural and anthropogenic factors for the shaping of the natural heritage. Arrows denote influence.

Over millennia, farming and livestock husbandry have developed practices and methods which have produced a remarkable structural and habitat diversity at landscape and regional levels. This includes natural hedges, terracing, grazing patterns, burning, transhumance, crop rotations, cultivars, varieties, livestock breeds, crop mixtures, mixed grazing–cultivation systems, ley patterns, forest openings, irrigation systems, harvest timing, transport and storing of crops and fodders, herd composition and movements, predator control, guarding against predators and pests, natural fertilisation, crop protection, provisions for wildlife, risk assessment and control, disposal of corpses, temporary animal enclosures, feeding patterns, livestock diversity, ploughing and soil protection techniques, traditional architecture, quality of materials, aesthetic value of infrastructures, and so on. The temporal and spatial combinations of all these are also included. These human interventions provide disturbance to ecosystems and it is now widely accepted that small-scale disturbances taking place frequently result in higher species diversity than heavy disturbances or the absence of disturbance. Whether or not human intervention is totally excluded, ecosystems as living systems would go on changing because natural factors continue to act in any case.26 Hence, one way or another, conservation of biodiversity or of landscapes or both entails a certain level of management.

Given all the above there are two important problems:

(1) As we have seen, management of ecosystems is necessary. In most cases rehabilitation and restoration will also be necessary since ecosystems change continually, but what conservation science alone will never be able to answer is what the goals of this management effort will be. What past biotic community that existed in a given area should be selected as the target for restoration efforts or as a benchmark situation? The answer to this question is by no means obvious. There is confusion even among conservationists about what exactly conservation means in a cultural landscape. As Rackham put it ‘… Ecological science as a whole has still not understood what conservation means in a cultural landscape’.27

(2) Even if it were possible to define such goals, it is commonplace that the decisions about what these patterns and mixes of farming, forestry and other human activities would be are not governed by the will to shape or maintain the natural heritage but rather from combinations of other much more influential factors, at various spatio-temporal scales such as values, economy, markets, technology, science, necessities, global balances, politics, customs and tradition, religion, stochastic events, philosophical perceptions, and so...