- 284 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

China's Internal and International Migration

About this book

One consequence of China's economic growth has been a massive increase in migration, both internal and external. Within China millions of rural workers have migrated to the cities. Outside China, many Chinese have migrated to other parts of the world, their remittances home often having a significant impact within China. Also, China's increasing links to other parts of the world have led to a growth in migration to China, most interestingly recently migration from Africa. Based on extensive original research, this book examines a wide range of issues connected to Chinese migration.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access China's Internal and International Migration by Li Peilin,Laurence Roulleau-Berger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Ethnic Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Inequality and migration

1

The work situation and social attitudes of migrant workers in China under the crisis

China’s most significant achievement since reform and opening began 30 years ago is its fast development: from 1978 to 2008 China’s economy grew at an annual rate of 9.8 percent. The development miracle demonstrated by China’s path was brought about by a variety of factors, which include the establishment of a socialist market economic system full of vitality and the realization of the rapid advance of industrialization and urbanization in the social field. These factors certainly also include a low population growth rate, an adequate supply of labor, the continuous decline of the social dependency ratio, and so on. Other very important factors are the mobilization of the enthusiasm of the masses and, especially, the transfer of hundreds of millions of farmers from agricultural work to non-agricultural fields such as the industrial and service sector, which greatly improved the labor productivity of the whole society to make “Made in China” a new phenomenon that has captured the attention of the entire world.

However, the global financial crisis that originated in the United States’ sub-prime mortgage crisis in 2008 has had a profound impact on China’s economic prosperity, especially on the employment and working conditions of Chinese migrant workers. China has thrice experienced relatively serious employment tensions since reform and opening, but the working population mainly affected each time was different. The first was a situation in which the return of more than ten million “educated youth who went to work in mountainous and rural areas” to cities in a short time at the initial stage of reform and opening led to very grave employment tensions in urban areas; the second was when the large-scale reform of state-owned enterprises from 1998 to 2003 led to a total of 28.18 million layoffs; the third is the current situation, in which the employment of tens of millions of migrant workers was affected by the influence of the current international financial crisis. As the international economic situation has deteriorated, demand for Chinese products has fallen sharply. According to figures published by Chen Xiwen, director of the Office of the Central Rural Work Leading Group of the CPC, at a State Council press conference on February 2, 2009, about 20 million migrant workers across the country, or 15.3 percent of all migrant workers, lost their jobs due to the financial crisis;1 the vice minister of the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security, Yang Zhiming, also revealed that of the 700 million migrant workers who returned home during the 2009 Spring Festival, 80 percent had returned to cities, but 11 million of them had not yet found employment.2 In the face of employment pressure, migrant workers’ labor conditions also suffered some setbacks, such as the resurgence of the problem of defaulting on the payment of migrant workers’ wages, a low rate of signing labor contracts with migrant workers in industries with great mobility and small enterprises, and the sequential decline in the rate of migrant workers’ participation in social insurance.

Migrant workers constitute a major component of China’s industrial work-force and are also an important force supporting the continuous growth of the Chinese economy. Working and living conditions and the social attitudes of migrant workers are closely linked to China’s economic growth, social stability, and the improvement of farmers’ living conditions – the subject investigated in our survey report. Data used in this report came from the second-wave “General Survey of China’s Social Situation,” which was conducted by the Institute of Sociology of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences from May to September 2008.3 The national sample survey covers 134 counties (cities, districts), 251 townships (towns, subdistricts), and 523 villages (neighborhoods) in 28 provinces, municipalities, and districts across the country. We successfully interviewed 7,139 residents aged 18 to 69; the survey error is less than 2 percent, which complies with the scientific requirements of statistical inference.4 We formed the research report based on data both from this survey and from the first survey in 2006.

The working conditions and treatment of migrant workers

Results from the survey show that compared with 2006, working conditions and the treatment of migrant workers have improved to a certain degree, but still have a long way to go compared with those of urban workers.5

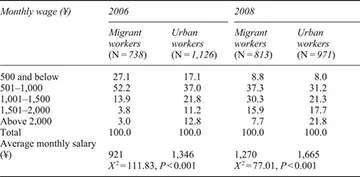

The biggest benefit for migrant workers is the wage increase. The survey shows that the average monthly wage of migrant workers rose from ¥921 in 2006 to ¥1,270 in 2008, an increase of nearly 38 percent. In 2006, the monthly wages of nearly 80 percent of migrant workers were below ¥1,000, while in 2008 53.9 percent of migrant workers earned a monthly income of more than ¥1,000. The wages of migrant workers grow faster than those of urban workers, so the wage gap between migrant workers and urban workers is narrowing. Nevertheless, the income gap between migrant workers and urban workers is still very significant and the average monthly wage of migrant workers in 2008 is only 76.2 percent of that of urban workers (see Table 1.1).

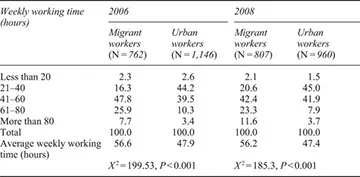

However, compared with 2006, the labor intensity of migrant workers remains very high. The average weekly working time of migrant workers was 56.6 hours in 2006 and 56.2 hours 2008, which are almost identical. The average weekly working time of urban workers was also basically unchanged: 47.9 hours in 2006 and 47.4 hours in 2008. While their average income is far below that of urban workers, the average daily working time is longer than that of urban workers and is about 8 hours. In 2006, 81 percent of migrant workers and 77 percent in 2008 worked more than 40 hours per week and in both years about one-third of migrant workers worked more than 60 hours per week (see Table 1.2).

Table 1.1 Comparison of the monthly income of migrant workers and urban workers (%)

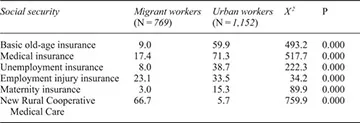

The more important difference between the treatment of migrant workers and urban workers lies in social security (see Table 1.3). For example, in terms of old-age insurance, 9 percent of migrant workers have access to basic old-age insurance, while the figure is 59.9 percent for urban workers; the percentage of migrant workers who enjoy medical insurance for workers or residents is 17.4 percent, while the figure is 71.3 percent for urban workers; 8 percent of migrant workers are covered by unemployment insurance, while only 38.7 percent of urban workers are; the gap of employment injury insurance between migrant workers and urban workers is smaller: 23.1 and 33.5 percent, respectively.6

Table 1.2 Comparison of the weekly working time of migrant workers and urban workers (%)

Table 1.3 Comparison of the social security benefits enjoyed by migrant workers and urban workers (%)

Nevertheless, two-thirds of migrant workers have participated in New Rural Cooperative Medical Care.7

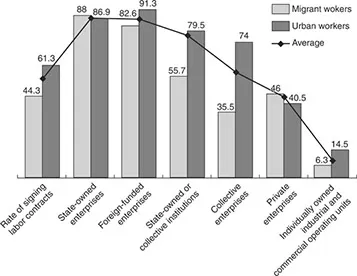

Protection of the labor rights of migrant workers also lags behind considerably. Although the Labor Contract Law started to be enforced on January 1, 2008, in our investigation half a year later we found that the rate of signing labor contracts with migrant workers was only 44.3 percent, 17 percentage points lower than the rate of signing labor contracts with urban workers (61.3 percent). By comparing the rates of signing labor contracts of different organizations, we can see that the rates of signing labor contracts of state-owned enterprises and foreign-funded enterprises are relatively high – all above 80 percent – and that there is minimal difference between the rates of signing of migrant and urban workers. The rate of signing labor contracts for urban workers at state-owned or collective institutions is 79.5 percent, but the rate of signing for migrant workers at such institutions is far lower than that of urban workers (only 70 percent of the latter). The rate of signing labor contracts of collective and private enterprises is relatively low (only 55 ~ 44 percent on average), and the gap between migrant workers and urban workers at collective enterprises is the biggest (35.5 : 74 percent). The rate for individually owned industrial and commercial operating units is very low – 10.4 percent on average – and for migrant workers it is only 43 percent of that of urban workers (see Figure 1.1). From this it can be seen that in order to protect the rights of workers, especially the rights of migrant workers through the Labor Contract Law, we have not only to substantially increase the rate of signing labor contracts, but also to pay close attention to household registration and status discrimination with regard to the signing of labor contracts in different types of organization.

In the first wave of the “General Survey of China’s Social Situation” in 2006, we found that the income gap between migrant workers and urban workers did not originate from household registration and status discrimination, but was caused by the difference between the two groups in terms of human capital (educational level and labor skill level).8 The second survey results are the same. In terms of education, 79 percent of migrant workers received junior secondary education or lower, 18.1 percent received senior secondary or secondary vocational education, and those who received post-secondary education or higher-level education account for only 2.9 percent, a very small percentage. At the same time, 70 percent of urban workers received senior secondary or higher level and 35 percent received post-secondary or higher-level education. In terms of the skills required by the work undertaken, the percentage of migrant workers engaging in physical and semi-physical work reaches 61.4 percent, while the percentage of urban workers engaging in work that requires professional skills is 58.3 percent, 20 percentage points higher than that of migrant workers (see Table 1.4).

Figure 1.1 Comparison of the rate of signing labor contracts with migrant and urban workers (%).

Table 1.4 Comparison of the job skills of migrant workers and urban workers (%)

| Job skills | Migrant worker... |

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of illustrations

- Notes on contributors

- Preface I

- Preface II

- Acknowledgments

- List of abbreviations

- PART I Inequality and migration

- PART II Social exclusion and integration

- PART III International migrants in China and social capital

- PART IV Chinese migrants outside China and transnational spaces

- Index