![]()

Holocaust Survivors: Resilience Revisited

ROBERTA R. GREENE

School of Social Work, University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas

This article revisits the findings of an earlier study, “Holocaust Survivors: A Study in Resilience,” that appeared in the Journal of Gerontological Social Work in 2002. That study's findings were generally consistent with other research related to resilience that suggested that survivors rebuilt their lives, forming families, establishing careers, and engaging in community service. These findings are also consistent with the theme of this issue, which celebrates the day-to-day struggles and challenges that survivors overcame.

This article revisits the findings of an earlier study, “Holocaust Survivors: A Study in Resilience” (Greene, 2002), that first appeared in the Journal of Gerontological Social Work in 2002. The 2002 study presented the results of qualitative interviews with 13 Holocaust survivors who recounted their stories of purpose and hope. Themes were developed that revealed how each survivor overcame the untoward circumstances of this time of extreme crisis and how they came to live with their memories and successfully overcome the trauma of the Holocaust.

The major themes of that article are revisited here using data from the research project “Forgiveness, Resiliency, and Survivorship Among Holocaust Survivors” (hereafter, the Templeton study) funded by the John Templeton Foundation. The Templeton study included a quantitative study of critical aspects of the lives of 133 survivors and a number of smaller qualitative studies of a sub-sample of survivors that are published in this issue. The study incorporated a number of theoretical frameworks and measures to describe critical events in survivors' lives before, during, and after the Nazi Holocaust: (1) Greene's (2002, 2007) resilience-enhancing model, (2) Erikson's (1959) eight stages of development culminating in the healthy personality, (3) Danieli's (1981) Family Typology of Survivors, and (4) the Enright Forgiveness Inventory (Enright & Rique, 2004). These are discussed throughout this issue.

Each framework offered a perspective on how people dealt with extreme stress and trauma and what was required for them to survive and then make meaning of these events, adapt, and grow (Greene & Graham, 2009). A Holocaust Survivorship Model was created to suggest how individuals, families, and communities developed a positive engagement with life after long-term exposure to adverse and even life-threatening events (Greene, Armour, Hantman, Graham, & Sharabi, this issue).

INTRODUCTION

There is a rich body of literature on the long-term effects of the Holocaust. After World War II, researchers tended to base their studies primarily on survivors’ clinical records (Chodoff, 1963; Krystal, 1979; Krystal & Niederland, 1968). This led them to emphasize the negative effects of the Holocaust experience (Glickman, Van Haitsma, Mamberg, Gagnon, & Brom, 2003), and leading mental health practitioners adopted the perspective that survivors were unable to deal effectively with loss and problems of guilt and shame (Chodoff; Krystal). However, these conclusions were later questioned, as empirical evidence increasingly suggested that there was “diversity in long-term effects of the Holocaust on survivors …. Some survivors report a high level of psychological distress, while others, who were exposed to similar experiences, report few, if any, symptoms” (Hantman, Solomon, & Horn, 2003, p. 126; see also Danieli, 1981, 1982, 1995).

These conflicting research findings posed conceptual and methodological issues that have yet to be resolved. For example, Shmotkin, Blumstein, and Modan (2003) argued that there may be an interplay of vulnerability and resilience among Holocaust survivors in late life, whereas other theorists have contended that there is growing evidence that despite their great loss, survivors and their families show remarkable resilience (Glickman et al., 2003; Greene, 2002).

The study by Greene in 2002 documented that resilience manifested even during the extreme conditions of the Holocaust and that effective communities could be sustained under the most severe situations. Although some survivors in her study reported anger and continuing disbelief in their old age, they recounted that during their time in concentration camps, they retained personal bonds, choice, and control by their own special—and sometimes secretive—means.

A 2009 study by Greene and Graham underscored that although adverse events can threaten people's psychological and social stability, only a small percentage of survivors experienced posttraumatic stress disorder. In fact, most showed remarkable “self-righting tendencies” (Garmezy, 1991, p. 460), or resilience. Thus, the authors concluded that the level of trauma and the course of long-term recovery from adverse events varies by individual, whereas the search for meaning after stressful events is a universal and essential task that may occur either naturally or sometimes brought forth through clinical intervention.

The concept of survivorship, or the complex phenomenon involving the ability to survive and recover from severe adverse events or traumas, is the focus of this issue. This article illustrates how survivors used “both their innate and learned abilities (i.e. traits) to engage in actions (i.e. follow adaptive coping strategies) that [allowed] them to respond to the adverse event [of the Holocaust], to deal with feelings of distress, and then begin to heal” (Greene & Graham, 2009, p. S77).

MARKERS OF RESILIENCE

Resilience Defined

According to the Encyclopedia of Social Work (cited in Greene, 2008), risk and resilience form a multitheoretical framework for understanding how people maintain well-being despite adversity (Greene, 2008). Resilience, a key component of survivorship, is “a pattern over time, characterized by good eventual adaptation despite developmental risks, acute stressors, or chronic adversity” (Masten, 1994, p. 5). Although resilience is sometimes thought of as a trait, it needs to be understood primarily as a process that evolves over time (Werner & Smith, 1992). With this in mind, the researcher examined the factors that contributed to resilience and how people were able to withstand the stressful conditions of the Holocaust and become resilient members of the post-war community.

In large measure, research to date has suggested that resilience is the variation in an individual's response to risk and a larger-scale phenomenon that explains the collective coping of community members (Greene, 2008). Two definitions of resilience were adopted for this study:

1.Fraser (1997) used the term resilience to describe adaptation to extraordinary circumstances (i.e., risks) and achievement of positive and unexpected outcomes in the face of adversity. His definition is used as the theoretical base for exploring cumulative risk and protective and resilience factors that contribute to survivorship among Holocaust survivors.

2.Masten (1994) suggested that resilience be viewed as the ability to maintain competence across the life span. This definition is used here to explore the degree to which survivors retained their competence through life course transitions.

Three Waves of Resilience Research

Richardson (2002) identified three waves of resilience research that resulted in the various approaches to data collection and interpretation used in this study. In the first wave, resilience inquiry, researchers explored the traits and environmental characteristics that enabled people to overcome adversity. For example, researchers were interested in the factors that helped people ameliorate or reduce risk. These variables, known as protective factors, often include (1) an engaging personal disposition, such as positive temperament, social responsiveness, and self-esteem; (2) a supportive family milieu, including warmth and cohesion; and (3) an extra-familial social environment that rewards competence (Garmezy, 1991). It is difficult to say how all of these factors influenced Holocaust survivors. However, Greene (Family Dynamics, the Nazi Holocaust, and Mental Health Treatment, this issue) provides some insight into the role of family support in survivorship.

In the second wave of inquiry, researchers investigated the processes related to stress and coping after adverse events, exploring the level of recovery and the long-term effects of adversity. A number of studies emphasized posttraumatic stress disorder, and others investigated people's self-righting tendencies. The divergent outcomes or findings from these studies may be related to the meanings people make of the Holocaust experience (Frankl, 1969), as discussed by Armour (this issue).

In the third wave of inquiry, currently under way, researchers have examined less verifiable resilience factors such as how people grow and are transformed after adverse events. This includes an interest in the process of self-actualization and in creativity and spiritual sources of strength (Richardson, 2002; see also Corley, this issue).

METHODOLOGY

Sample

A snowball sample of 133 Holocaust survivors was recruited from Jewish organizations in nine U. S. locations: Austin, Dallas, Houston, Los Angeles, Minneapolis, New York, New Jersey, San Antonio, and Washington, DC.

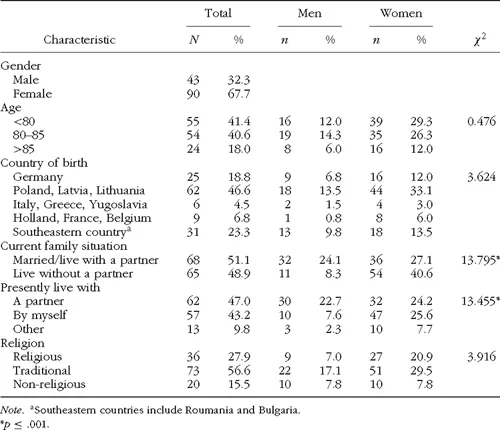

TABLE 1 Demographic Characteristics of Templeton Study Participants

There were 90 women (68%) and 4...