![]()

Part 1

Places

![]()

1 Life on the lines

People and places of the Korean border

Valérie Gelézeau

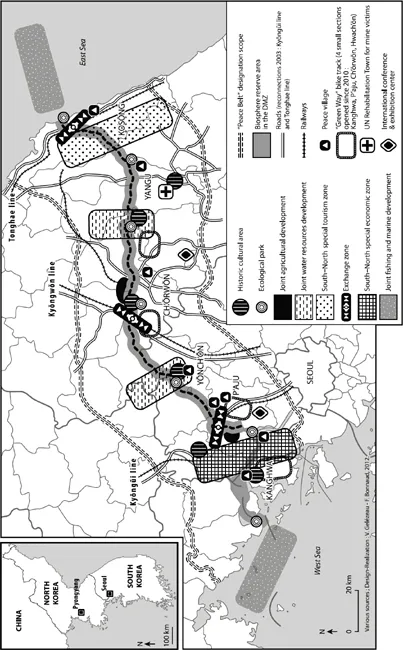

In keeping with the political atmosphere of the Sunshine era, South Korea’s main national planning institute, the Korean Research Institute for Human Settlements (KRIHS), in 2004 introduced the “Peace Belt” project.

Conceived as “a space especially set up to create and spread peace towards the divided Korean Peninsula,” the Peace Belt would provide “a place for exchanges and cooperation in the Demilitarized Zone and border between North and South Korea.”1 The Peace Belt stretches from east to west along the 255-mile-long Demilitarized Zone (DMZ), the current border between the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) and the Republic of Korea (ROK). Dotted with ecoparks and crisscrossed by major communication axes built along pre-division routes, it is meant to be an ecologically protected sanctuary providing a rare habitat for endangered wildlife. It would include two great North/South cooperation Zones (a joint tourist Zone to the east and an industrial and economic cooperation Zone to the west) and be based on joint development of inland and oceanic water resources (see Figure 1.1).

The Peace Belt is the imagined border of South Korean planning.

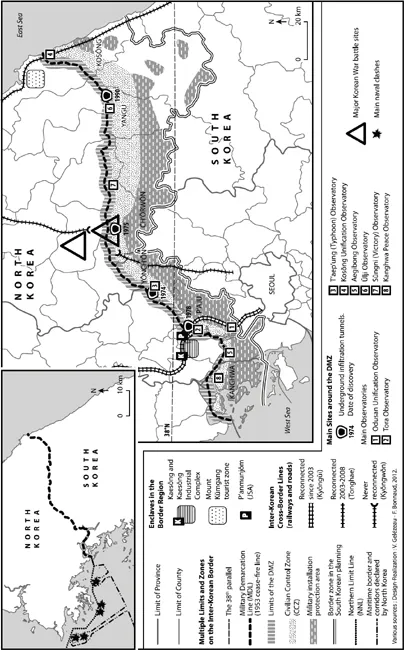

The projected Peace Belt strongly contrasts with the present infrastructure of the inter-Korean border (see Figure 1.2). It also conflicts with widespread views of it, which tend to focus on the fact that the 4 km swath of no man’s land separating the two countries – one of the most militarized borders in the world – represents a unique environmental sanctuary. This binary image of the border, in which heavily armed soldiers alternate with flocks of rare birds, has been central to South Korea’s commemoration of the 60th anniversary of the Korean War (1950–53).2 Its cumulative effect is to suggest a kind of stasis, as if this final relic of the Cold War is somehow frozen and will never lose its status as a militarized no man’s land or ecological sanctuary. It is the aim of the present chapter to blur this received view of the border.

In the provinces of Kyŏnggi and Kangwŏn, South Korean planning authorities have officially defined a “border Zone” (chŏpkyŏng chiyŏk). This Zone covers roughly 7,000 km2 (about seven percent of South Korea’s total area) and about 400,000 soldiers are stationed there. What, one may wonder, are the particularities of Korean border society and its environment? How do people envision their situation near the border? How do they talk about it and what is their experience of it? An examination of the Korean border region raises particularly interesting questions concerning the Seoul Metropolitan Region due to its proximity to the DMZ. It also raises the question of how the political relationship of the two Koreas has been reflected in spatial transformations along the border: did the border change and in what ways during the period of engagement (1998–2008)?

Figure 1.1 South Korean blueprint for the border area (2000–30)

Figure 1.2 The inter-Korean border

This chapter examines the inter-Korean border region through a geographical perspective focusing on space and landscape as social constructs. In doing so, it expands upon the vast scholarly literature in geography devoted to the spatial dimensions of state borders (Chang Yongun 2005; Foucher 1991; Guichonnet and Raffestin 1974; Rumley 1991; Wastl-Walter 2011) as artifacts of political power that often persist long after the particular circumstances which led to their emergence have been superseded (Newman 2006). Political borders create particular spatial effects on nearby regions by shaping physical and social landscapes. Insofar as the “other” has a considerable impact on the spatial organization of the Self, the border is a spatial interface.

A considerable amount of research has been produced in South Korea on the DMZ and the inter-Korean border.3 As the Peace Belt project shows, it has a peculiar status in the context of rapprochement as a place to “prepare for the peaceful reunification of the Peninsula” (Kim Chaehan 2003: 7). The South Korean research program mostly focuses on developmental issues and is dominated by economic geography and environmental management. The present chapter, by contrast, takes a more cultural-geographical approach, exploring various aspects of the border region or borderlands – terms I will use interchangeably to simply denote areas located near the border.4

Lines and limits

In South Korea, the border region is structured by various limits directly connected to the 1953 Armistice Agreement, which established the Military Demarcation Line (MDL) as the cease-fire line (hyujŏnsŏn) around the 38th parallel at the end of the Korean War.5

The MDL (kunsa pun’gye sŏn) as well as the Northern Border Line (pukpang han’gye sŏn), located 2 km north of the MDL, and Southern Border Line (nambang han’gye sŏn), 2 km south, are the inner limits of this composite border. In between lies the 4 km wide DMZ (pimujang chidae), a buffer Zone devoid of human settlement from which both armies withdrew in keeping with the terms of the armistice (see Figure 1.3).

It is impossible for civilians to enter the DMZ except under exceptional circumstances and then always accompanied by a patrol and equipped with armored vest and helmet.

Beyond the Northern and Southern Border Lines, the territorial limits of each country have been established by the national governments of North and South Korea respectively. In North Korea, the border region lies within 50 km distance from the northern border line. In November 2007, a day trip from Pyongyang to the DMZ allowed basic observation of this 50 km checkpoint and two others closer to the border as well as of the area’s particularly dense concentration of military units. In the South, the Korean Defense Minister (kukpangbu changgwan) established the Civilian Control Line (min’ganin t’ongje sŏn or mint’ongsŏn – CCL), which runs south at a distance of 10 to 15 km from the MDL and delimits the Civilian Control Zone (min’ganin t’ongje chiyŏk – CCZ), where civilian access is restricted to authorized pass bearers (see Figure 1.4).6

Figure 1.3 The DMZ as seen from a guard post in Ch’ŏrwŏn

Note: The front line defense systems including barbed wires, a patrol lane and a defense wall are constantly watched by guard posts.

Source: Valérie Gelézeau, 2009

Military Installations Protection Districts (kunsa sisŏl poho kuyŏk – MIPD) are also delineated by the Secretary of Defense. These are special districts (including military bases and neighboring settlements) located up to 50 km away from the MDL. In the MIPD, many restrictions are imposed on development, including special zoning (certain types of industrial activity are prohibited) and building code (a ban on high-rise structures) restrictions. The total surface area of South Korea’s MIPD is 5332 km2, or about five percent of the national territory. The better part of this five percent is located in Kyŏnggi and Kangwŏn provinces: 2213 km2 in the former (22 percent of the total surface of the province) and 2,408 km2 in the latter (14 percent of total of the province). MIPD cover 93 percent of P’aju City, for example, 98 percent of rural Yŏnch’ŏn county (kun) and more than 99 percent of Ch’ŏrwŏn county in Kangwŏn province. With 44 percent (1,891 km2) of its territory covered by MIPD, the Northern part of Kyŏnggi province remained relatively underdeveloped until the mid-1990s (Pak Samok 2005).

Figure 1.4 The CCL checkpoint on the way to P’anmunjŏm

Note: This checkpoint marks the crossing of the Civilian Control Line on Highway 1, which was reconnected in 2003 as far as Kaesŏng, 21 km further down the road. The traffic board mentions Pyongyang, but even South Koreans authorized to penetrate the Civilian Control Zone will have to interrupt their journey at P’anmunjŏm.

Source: Valérie Gelézeau, 2008

These limits are sometimes hard to precisely trace on a map, both because military secrecy makes field research difficult and because some have in fact moved: since 1953, both countries have displaced guard posts within the DMZ in order to expand their respective territory. In Ch’ŏrwŏn county, the Administration moved the CCL northwards to facilitate the inhabitants’ life. It is now roughly 2 to 5 km from the DMZ and some traces of the previous location (abandoned guard posts) are visible. Yet other front lines – e.g., the secondary anti-tank defense system in the South Koran plains behind the DMZ – are difficult to trace because they have never been openly discussed.

The border is comprised of a final demarcation, this time clearly visible on Google Earth captures of the border. This line is the product of the deeply contrasting landscapes of North and South Korea. When I traveled from Pyongyang to Kaesŏng and P’anmunjŏm during the 2007 trip, the contrast between North and South Korean border regions was immediately apparent. In contrast with the forested highlands of South Korea, the North Korean hills were almost entirely bare and deeply scarred by erosion.

Contested territories and outposts on the front line

The border region includes territories of contested status characteristic of the “hot borders” of military confrontation (Chang Yongun 2005: 57–118; Foucher 1988). The maritime border, for example, has still not been clearly established (Kim Chae-Han 2001: 79–125; Gelézeau 2011).

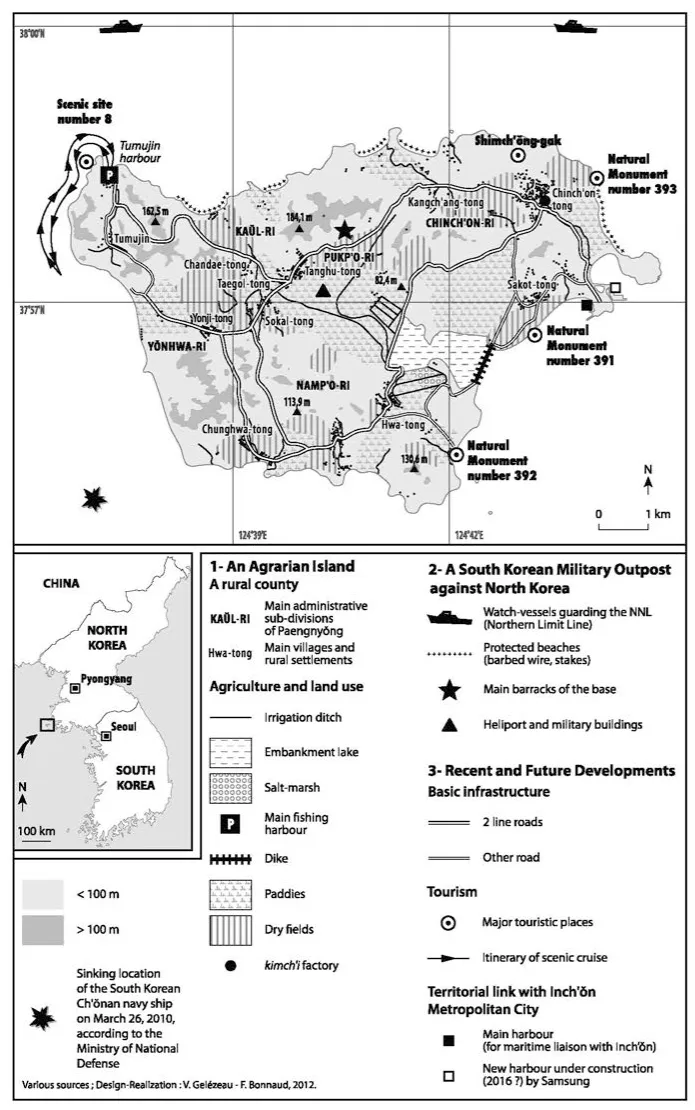

As a result, located just below the 38th parallel and less than 25 km from the North Korean coast, Paengnyŏng Island, like the four other South Korean islands of Ongjin county (kun), though clearly South Korean land, lies in an area of indefinite maritime status from the point of view of international agreements and inter-Korean maritime borders alike (see Figure 1.5).7

Fishing activities around Paengnyŏng are restricted by a sunset to sunrise curfew and a ban on sailing more than one nautical mile to the north. But stories of fishermen accidentally crossing the Northern Limit Line (NNL) in foggy weather abound and North and South Korean ships clashed in June 1999, September 2002 and November 2009. These three clashes have certain features in common and together underscore the ambiguous status of the maritime border region. They are also part of a broader contest between North Korean, South Korean and Chinese boats for control over non-delimited fishing territories (Gelézeau 2011). Similarly, the sinking of the South Korean corvette Ch’ŏnan in March 2010 and the shelling of Yŏnp’yŏng Island in November 2010 should be seen in the framework of these unsettled territorial disputes.8

The presence of various types of outposts guarding front line territory is yet another characteristic of the composite inter-Korean border.

As South Korea’s northernmost island, Paengnyŏng (5201 inhabitants in 2012) is a highly strategic outpost. South Korea’s twelfth largest island (46 km2), it is connected to Inch’ŏn City (on which it depends administratively) by two ferry companies, each running one round trip per day, weather permitting. When the conditions are good, one reaches the small harbor of Yonggip’o in four hours. Crossing the island by its main road from Yonggip’o to the tiny port of Tumujin allows one to observe the main features of the landscape: flatlands occupied by paddies and lower hills covered by dry fields, including many plots of ginseng cultivation under black plastic. Forests cover the island’s higher elevations and a military base is located at its center.

In 2004, 60 percent of the active population was engaged in farming, seven percent were fishermen, the rest (33 percent) being involved in various service activities (mainly commercial and/or related to tourism). Farming determines the spatial organization of the island, and more than 1,700 hectares of paddy fields have been created by land reclamation projects since the 1970s, or more than a third of the island’s current surface area. These great reclamation projects were paid for with special government border region funds intended to assure permanent South Korean settlement on the island despite severe demographic decline (the island’s population dropped from 12,581 inhabitants in 1970 to 5201 in 2012). The dominant farming economy, extensive supply of reclaimed land and larger average property size (1.6 hectares compared to the national average of 1.1 hectares) are a direct consequence of the island’s proximity to the border. As a result, the island’s economy is less evenly balanced between farming and fishing than that of other South Korean islands and coastal villages. Like other farming villages behind the CCL, farmers are given incentives to stay and occupy the outpost.

Figure 1.5 Paengnyŏng Island: a South Korean outpost in disputed waters

Located “in front of them all”9 as it stands at the village’s entrance, the village of P’anmunjŏm, where the armistice was signed, is crossed by the MDL: it is another typical outpost of this border. As a Joint Security Area (JSA), this enclave is occupied by the armies of both Koreas as well as the United Nations Command Military Armistice Commission (UNCMAC ) and the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission (NNSC). Up till the 1970s, it was one of the only places where the two Koreas came into contact, though these contacts were restricted to military personal. When inter-Korean dialogue started at the beginning of the 1970s, the Red Crosses of the two countries opened liaison offices in the JSA as well as cross-border phone lines connecting them, thereby ending the era of exclusively military contacts between the two countries. But in August 1976, the so-called “Axe Murder” accident led to the reorganization of the jointly occupied enclave and the construction of a small wall on the MDL to further separate the two parties and prevent such accidents from happening in the future. This wall is visible from the most famous spot of P’anmunjŏm, where the barracks that were until 1994 used for inter-Korean dialogue still stand.

Finally, the military bases and the towns adjoining them, or kijich’on in Korean, are the most frequently found type of outpost guarding the South Korean borderlands from the North Korean threat. Some of them are due to the presence of the US Army on South Korean soil: five of the six largest US kijich’on in South Korea are located in Seoul or the province of Kyŏnggi. For example, in 1963, 40 percent of the territory of Tongduch’ŏn (Kyŏnggi province) was confiscated and chartered to the US Army for the purpose of creating a 40 km2 military base (Kim Pyŏngsŏp 2008). During the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s, soldiers spent considerable amounts of money on leisure and entertainment (including prostitution, a serious issue for these towns) in the area neighboring the bases (Moon Katharine 1997; Yea 2008).

Connected lines abandoned: the end of inter-border cooperati...