The ‘Middle Kingdom’ has come a long way in the last few decades, its economy has burgeoned and its prosperity has flourished. Chinese management has evolved greatly too but is now at the ‘crossroads’, as the People’s Republic of China celebrates the 60th anniversary of the ‘Liberation’ led by Mao Zedong and the 30th anniversary of the economic reforms launched by his successor, Deng Xiaoping. In this symposium, we review its past legacy, its evolution to date, as well as its options, covering a wide range of management topics. As ownership of its enterprises has opened-up and has become more fragmented, state-owned firms arguably no longer dominate the scene, nor does their management model. Being a manager has also become more complex and diversified, as well as more professional. The Party has proclaimed the ‘Harmonious Society’ as the route to reconciling economic performance with social justice. This edited collection asks what are the next steps and will assess the current directions in which Chinese managers are developing, as its economy now has to cope with a slowdown in the face of global uncertainty.

Background

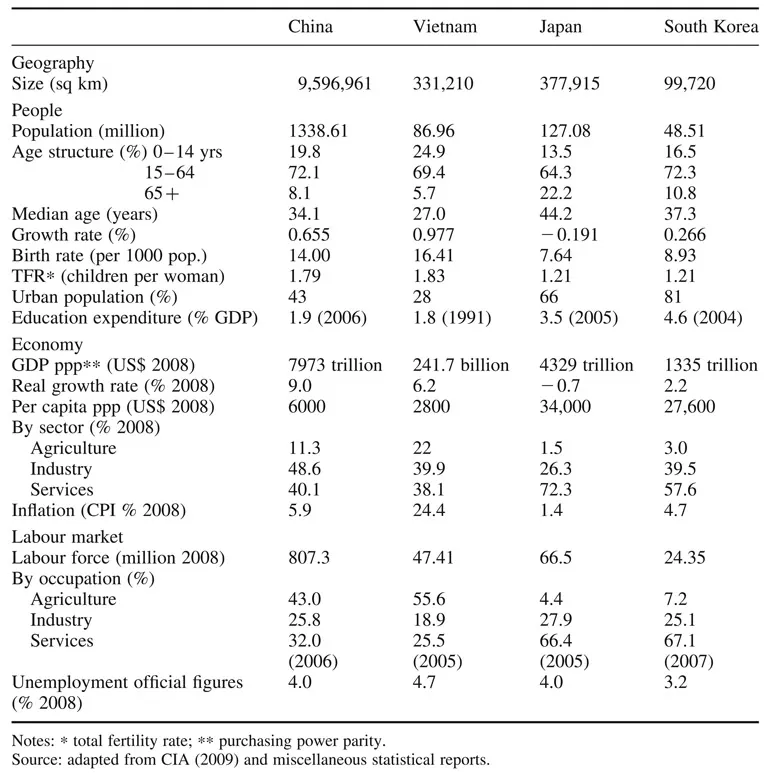

Today, the PRC is increasingly seen as an ‘economic superpower’ (World Bank 2009). China’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2008 was said to be over US$4.4 trillion, somewhat smaller than Japan’s but predicted to overtake it in 2010, if as yet only a third of that of the US. The outward investment of China was around US$56 million in 2008. Some see the PRC as umbilically linked to the US in a relationship called ‘Chi-merica’ (Ferguson 2009), constituting what has been dubbed the ‘G2’; it has now become the biggest lender to the US and the RMB (yuan), if possibly overvalued, is predicted to become a ‘reserve currency’ at a future date (The Economist 2009a, pp. 1–2). Its massive financial stimulus policy of US$586 billion to counteract the current economic crisis has been praised by the International Monetary Fund (IMF 2009) to better compensate for the fall in exports and the rise in unemployment at the end of 2008 (China Economic Review 2009). Even so, it has indeed become the new Asian ‘giant’ economy (Bergsten et al. 2008, World Bank 2009), and we can here clearly see China’s achievement, in a comparative context, for example its high rate of economic growth, vis-à-vis its neighbours, one ‘socialist’ (Vietnam) and the other two ‘capitalist’ (Japan and South Korea), in Table 1.

Table 1. Comparative contextual factors – China vis-à-vis its neighbours, one socialist and the other two ‘capitalist’ (2009, est.)

This table is also of interest as it shows some interesting contrasts, such as in terms of size (geographical, population and labour force) and relative importance (employment and contribution) of sectors. For instance, in terms of (1) population structure, 8.1% of the population is over the age of 65 in China, in Japan, 22.2%; (2) birth rate, 14.0 in China, 7.6 in Japan; (3) urban, 43% in China, 66% in Japan. Similarly, in terms of percentages of the labour force in different sectors, in China 43% are in agriculture, 26% in industry and 32% in services, while in Japan the figures are 4.4%, 27.9% and 66.4% respectively. Even more telling is the percentage of GDP each provides; for example, in China 11.3% comes from agriculture, 49% from industry and 40% from service, while in Japan the figures are 1.5%, 26.3% and 72.3% respectively.

In this symposium, we review the evolution of management in the PRC over recent years, which we see as having been modernized pari passu with the transformation of its economy. As ownership has now opened-up and has become more fragmented, the state-owned enterprises (SOEs) that once dominated its industrial landscape are no longer as prominent as they were (Garnaut et al. 2005, Zeng 2005, Warner 2009, 2010a, 2010b). Markets now drive the economy and management has also become more complex and diversified, as well as more professional and less ideological (Chen 2008). Even so, the state still plays a key role in orchestrating the score (Huang 2008, The Economist 2009b, Scissors 2009). Right now, the Party is said to be attempting to blend Marxist-Leninism with traditional notions of Confucianism (Bell 2008) as it seeks to cope with the growing contradictions in Chinese society, such as relate to inequalities of wealth and income, and more fairly deal with its labour–management relations by promoting the ‘Harmonious Society’. This edited collection asks what are the next steps to take and will assess the current directions in which Chinese managers are developing as the economy slows down in the face of global uncertainty (see the variety of areas of management in Rowley and Cooke [2010]). We can see the range of the contributions in the symposium in the overview of contents in Table 2 below. This is in terms of main themes, organizations and sectors and locations covered.

Contributions to this symposium

We now present a summary of each of the contributions to this symposium, in the following section. First up is a study by Warner and Zhu, which looks at the relations in the workplace between labour and management. It examines the challenges now facing China’s increasingly complex ways of managing people in the new economic, political and social environments of the twenty-first century and how managers are adapting to the new concept of a ‘harmonious society’ to which the new Chinese leadership currently aspires. The authors hypothesize that this search for harmony, built on Chinese cultural values, represents what amounts to what can be conceptualized as a ‘coping mechanism’ to deal with the existing and potential conflicts now facing Chinese society. Labour– management relations in the workplace are accordingly now changing fast. The older ways of people management are being replaced with newer ones. Notions of human capital and human resources (HR) are now increasingly de rigueur. The more ‘human resources management’ (HRM) replaces ‘personnel management’ in China, the more of the old people management ethos of the planned economy goes out of the window. HRM is now more typical of the non-state sector.

However, it might be argued that this new way of managing may be more often found in most of what have been called ‘learning organizations’, such as those more ‘open’ Sino–foreign joint venture (JV) enterprises or multinational companies (MNCs)

Table 2. Overview of content: themes, sector/organization and locations

operating in China. In such firms, we are likely to find new management practices that have been initially transplanted when the JV was initially founded, for example, by the overseas partner from its home base to, say, Beijing or Shanghai.

This contribution concludes that the changes in the relations between labour and management reflect the impact of globalization on economic restructuring and enterprise diversity, as well as the changing role of trade unions and their efforts to protect workers’ rights and interests in the light of these developments. Yet, the authors believe that there will indeed have to be another ‘Long March’ for the Party/state and unions, as well as other civil groups in China, before the partners can reach a new social equilibrium.

In the next contribution included in this collection, Kriz and Keating examine interpersonal trust which they argue may be identified as a critical issue for Western firms attempting to do business in China. To go ‘within’ Chinese culture and what some refer to as ‘inside-out’ or ‘bottom-up’, their study adopts a grounded interpretive approach, employing mainly qualitative techniques. These include using ‘rich’ and ‘thick’ descriptions and ‘in-depth’ semi-structured interviews.

Initially pilot interviews were conducted with Chinese individuals resident in Australia and this was later followed up with ‘face-to-face’ interviews in Beijing, Shanghai and Xiamen, as well as the non-Mainland Chinese markets of Taipei and Hong Kong. A key goal of this research was to offer a more indigenous or native Chinese definition for trust. After coding, processing and analysing the data, it became evident that Chinese defined trust (xinren) as the ‘heart-and-mind’ confidence and belief that the other person will perform, in a positive manner, what is expected of him or her, irrespective of whether that expectation is stated or implied.

Another important strand of the study was to pin-point potential antecedents of trust, as well as a conceptual framework. The study identified that what the Chinese refer to as trust or xinren is reserved for a minority of people and is erected on several important elements, like honesty, sincerity, help, reciprocity and performance over time. The relationship between xinren and its associated construct in Chinese business is called guanxi. The tag xinren is really reserved for a few select relationships, whereas guanxi is built around more extended connections and a larger network. The study suggests that lower forms of trust can of course be built from initial connections and guanxi, but ‘deep trust’ or xinren does not occur until a threshold is achieved. At this level, the bonds become very strong.

This finding is, the contributors believe, an important addition to the literature on the subject, as those business people operating in China and relying on guanxi may be overestimating the depth of their potential connection’s commitment. Crucially, deeper levels of trust, they argue, are built on both cognitive and affective aspects and are not simply instrumental or emotional as reported in recent literature. They believe that what they calls an emic approach to understanding xinren is a timely contribution to the growing importance of doing business in Chinese markets and has important implications for both theory and practice.

After this, Cunningham and Rowley, in their study of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) in China, discuss the importance of HRM. As the importance of SMEs there has increased, they see it as critical to review research on HRM in such firms, in order to identify the ‘gaps’ or areas that may exist in current coverage. Therefore, the aim of the current study is to provide an overall examination of the research on HRM in SMEs in China. The authors begin with a discussion of the literature addressing HRM in this category of firms by looking at the nature of HRM in SMEs and the importance of contextual factors on its ‘take-up’ in enterprises. Then, research methods and data collection processes are presented; after this, the findings of the research are set out. Finally, the study draws together some conclusions and outlines possible future directions.

While the results of this review suggest that informality is the key feature of HRM in SMEs in China, the findings of the current study illustrate that two key factors contribute to the informality of the HRM approach in such firms in China. One relates to the specific characteristics of SMEs (that is, external uncertainty and the ‘dictatorship’ of the owner-manager), and the other is the market environment. In other words, this review confirms that HRM practices in SMEs in China are rather more informal than those formalized and systematic procedures prescribed in the concepts of Western HRM ‘best practices’. The findings of this review also demonstrate that traditional Chinese culture limits the applicability of HRM in non-Western settings, while institutional factors create barriers to effective management practices.

Although China provides a dynamic environment for SMEs to grow and the evidence suggests a linkage between HRM and organizational performance, the current study implies that it is clear that contextual influences restrain the pace and depth of HRM changes in SMEs. Even though the progress of SME-related HRM studies is promising, this review suggests that the research on this in China is sparse and limited, as well as geographically biased and concentrated.

Next, Shen’s contribution investigates levels of employees’ satisfaction with HRM practices in Chinese privately owned enterprises (POEs) in manufacturing and differences in satisfaction between different employee groups. In China, he argues, HR is managed ‘differently’ according to the type of pragmatic and market-oriented firms, resulting in a significant growth in labour disputes. However, little is known about how employees in this sector perceive HRM policies and practices.

This study posits that the levels of employees of POEs satisfied with HRM ranged from low to high. Employees were relatively more satisfied with performance appraisal, particularly appraisal criteria and appraisal execution, than other HRM policies and practices. Employees were moderately satisfied with contract-based employment relations, the two-way selection process and performance-based rewards and compensation (see also Rowley and Wei [2009a, 2009b]), except for signing labour contracts and welfare and benefits. Employees were very dissatisfied with training provision and management development opportunities, and with the poor level of organizational support being offered for personal and management development.

This author concludes that during the past three decades the economic reforms have eroded Chinese employees’ sense of having a truly ‘socialist-egalitarian’ ideology. Employees’ satisfaction with the HRM reform varied significantly according to their own personal characteristics and experiences. The study points out that the ‘inequality’ in HRM practices is the key reason for variations in levels of satisfaction with HRM.

After this, in the next contribution, Cooke and He examine issues related to corporate social responsibility (CSR) which has been the subject of growing debate across an increasingly wide range of disciplines in social sciences and business and management studies. China’s manufacturing-based economy, producing a large share of world trade, they note, has been facing mounting pressure to take CSR issues seriously, with particular reference to environmental protection and labour standards. However, issues related to CSR and HRM remain under-explored, and existing studies on the topic focus primarily on labour standards in value chains. While research interest on CSR has grown significantly in China in recent years, few empirical studies have been undertaken to identify how companies, particularly those in the private sector, perceive CSR issues, what actions they are taking, if any, and what implications these may have for institutional bodies that seek to promote CSR in the country. This study addresses this research gap by investigating the current situation of CSR, of whi...