![]()

Introduction: The General Election of 2010

JUSTIN FISHER* & CHRISTOPHER WLEZIEN**

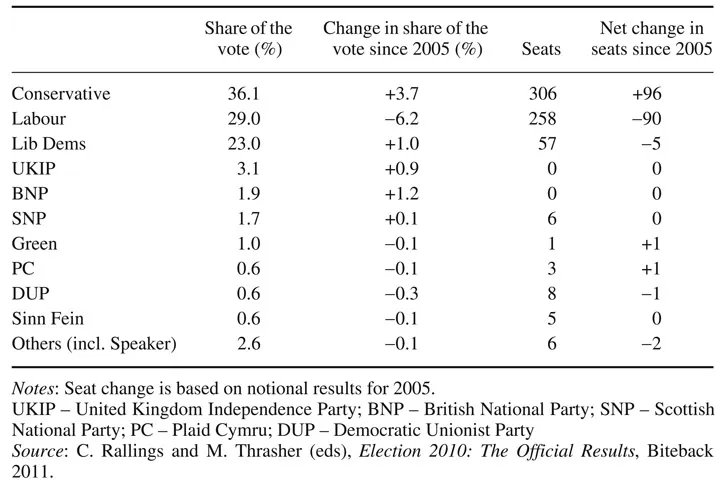

All elections have some element of drama to them, and all are memorable in their own way. But the 2010 election in the United Kingdom was significant in numerous ways. For example, only 65.1% voted for either the Conservative or Labour parties – a post-war low. Indeed Labour’s share of the vote was its second lowest since 1918 (only the vote share in 1983 was lower). By way of contrast, some minor parties performed well – although they gained no seats, UKIP secured the highest minor party vote share ever in a general election while, the Green Party won its first ever seat in the House of Commons. And record numbers of women (143) and non-white candidates (27) were elected.

Over and above these records, however, three aspects of the elections were especially noteworthy. First, of all, there were televised debates between leaders of the three largest parties. This idea has long been called for (particularly by broadcasters), but for a variety reasons (and, in particular, the desire of the incumbent not to provide the opposition with an advantage through ‘equal billing’) have not occurred in Britain until 2010. Now they are here, they are almost certainly here to stay.

Secondly, the election led to the end of 13 years of Labour rule. Previous Labour governments had never lasted two full terms, so the party’s achievement in serving three was a notable achievement. Nonetheless, just as the 1964 and the 1997 elections had delivered the final blows to long-standing one party government, so 2010 did the same. What made 2010 particularly significant however was that unlike 1964 or 1997, no single party assumed the reins of power. True, Labour’s victory in 1964 was only delivered with a majority of five, prompting another election two years later (producing a Labour majority of 97), but it was a majority nonetheless.

Thirdly, although the Conservatives ended up as the largest party by some margin, they were still some 20 seats short of a majority of just one. (In truth, an additional 16 seats would have been sufficient given that Sinn Fein MPs do not take up their seats at Westminster.) Not since the election of February 1974 had the result failed to produce a majority government in the Commons, and before that, we would have to go back to 1929 to find a similar outcome.

As Tom Quinn et al. show in this collection, such an outcome had the potential to lead to a variety of outcomes, though in reality only two were likely – a Conservative

Table 1. Result of the general election

minority government or a Conservative-led coalition with the Liberal Democrats. After five days of intense negotiations, the latter was formed and Britain began life under a coalition government for the first time since the wartime government in the 1940s, and in peacetime for the first time since the 1920s.1

As one might expect, there are a number of volumes that appear in the aftermath of an election, and indeed, we and many of our contributors have appeared in them. Each of the volumes serves a different purpose and each is excellent at what it sets out to achieve. This collection is different from the others. First, it is appearing a full year after the election. The reason for this is straightforward – modern election analysis requires the gathering of large, if not vast, amounts of data and the gathering and analyses of these data take time. The result is that this collection is the first to feature full length contributions on the 2010 election extensively featuring data from major studies such as the British Election Study and the Ethnic Minority British Election Study. Second, all contributions contained within this collection have been subject to intensive peer review. This process of courses lengthens the period between the election and publication, but the contributions featured here are all the better for it. Third, reflecting the fact that these contributions appear first in an academic journal, they are highly technical in places. This is to demonstrate how the authors have arrived at their conclusions in an appropriately scientific way. As a result, while it builds upon the excellent existing publications that are already in print, we think that this collection adds something substantial to our understanding of the 2010 general election.

We have organized the contributions in thematic and ‘chronological’ order. We begin with two papers looking at the election campaign and the impact of leaders, including the leaders’ debates. The 2010 election was especially noteworthy in this respect as all three main parties had new leaders who had never previously led an election campaign – the first time this had occurred since 1979. Charles Pattie and Ron Johnston use panel data from the British Election Study to assess the impact of the leaders’ debates on evaluations of the leaders, their parties, government performance and vote choice. They show that the debates did indeed influence voters’ thinking and decision-making in the run-up to the election, though it was the first debate that appeared to have the most dramatic effects. Jeff Karp, Daniel Stevens and Robert Hodgson examine which leadership traits are more important to voters. Using panel data from the British Election Study, they find that voters’ evaluations of party leaders varied substantially over the campaign and that for all three leaders, responsiveness and trustworthiness was a greater concern than variation in leaders’ knowledge. In addition, they find that alongside the debates, Party Election Broadcasts and newspapers influenced voters’ perceptions of leaders.

We then turn to two contributions examining the opinion polls. Mark Pickup, Scott Matthews, Will Jennings, Robert Ford and Stephen Fisher examine the competing explanations for over-estimation of support for the Liberal Democrats in polls. They suggest that it was very unlikely that there was a late surge of support for parties other than the Liberal Democrats, but also that methodological differences between different polling companies do not adequately explain the over-estimation of Liberal Democrat support. Rather, they suggest, there was a general polling industry problem in generating accurate results for the party. Yet, while polls during the campaign apparently over-estimated Liberal Democrat support, there was no such problem with the exit poll. When the results of this poll were announced by the three British broadcasters (BBC/ITV and Sky) as the polling stations closed, it is fair to say that there was surprise and not a little scepticism among television panels. Rather than showing the Liberal Democrat advance fore-shadowed by pre-election polls, the exit poll actually predicted the party losing seats. It was the third election in a row that exit polls using this methodology were startlingly accurate. Stephen Fisher, John Curtice and Jouni Kuha, who were closely involved with the poll, show how it was done and why the deployment of three key methodological principles has been vindicated. They caution, however, that should the next election be fought with a significantly reduced House of Commons with a greater equalization of constituency populations, and maybe under a different electoral system, then exit polling will face considerable challenges.

Our third section concerns voting behaviour at the election, looking first at overall patterns of voting in 2010. Harold Clarke, David Sanders, Marianne Stewart and Paul Whiteley use data from the British Election Study, which they direct. They show that as in previous elections, judgements about competence and leader images were very significant in determining voters’ choices. But they also suggest that the Conservatives’ failure to win an outright majority may partly have been a problem of the party’s own making. Clarke and his colleagues suggest that the Conservatives’ pre-election emphasis on massive public expenditure cuts and possible tax rises was an unwelcome message to a British electorate that was not as concerned with reducing the public debt as the Conservative leadership. The second contribution in this section draws on a long overdue in-depth study of voting patterns among Britain’s ethnic minority population. Anthony Heath, Stephen Fisher, David Sanders and Maria Sobolewska use the Ethnic Minority British Election Study to examine whether the different ethnic minority group continue to give overwhelming support to Labour. They find that substantial variation between ethnic minorities in their support for Labour, but that overall minority support for Labour remains double that of white voters.

Finally, we turn to the outcome of the election. Michael Thrasher, Galina Borisyuk, Colin Rallings and Ron Johnston consider the effects of the electoral system on the result. They show that while Labour has continued to benefit from the operation of the electoral system, its advantage relative to the Conservatives is now reduced in size and is explained much more by vote distribution and abstention biases. Such findings suggest that attempts to change boundaries, as is proposed by the coalition government, to reduce Labour’s advantage may be less successful than commonly thought. Our final contribution concerns not the election result per se, but one of its major consequences – the coalition agreement. Tom Quinn, Judith Bara and John Bartle utilize content analysis to evaluate which of the two coalition partners can be said to have gained most from the agreement in policy terms. They show that both parties secured considerable gains on their own policy priorities, but that relative to the size of their parliamentary representation, the Liberal Democrats made some impressive gains.

Overall, this collection analyses in depth the key questions arising from the election: the impact of leaders and the debates, the highs and lows of polling in the election, why the electors voted as they did, what impact the electoral system had on the result and who gained what from the coalition agreement. It also highlights the exceptional depth and importance of British electoral studies. We are immensely grateful to all the authors for submitting work of such high quality, for making changes necessitated by the peer review process, and responding to our numerous requests quickly and with the minimum of fuss. We are also grateful to the contributions’ referees, who must remain anonymous, but were invaluable in helping us decide which submissions to include in this collection and helping to ensure that the contributions were all of the highest quality. We hope that you enjoy reading this collection as much as we enjoyed editing it.

Justin Fisher & Christopher Wlezien

February 2011

Note

![]()

Party Leaders as Movers and Shakers in British Campaigns? Results from the 2010 Election

DANIEL STEVENS, JEFFREY A. KARP & ROBERT HODGSON

ABSTRACT There is an increasing recognition of the importance of party leaders in British elections. The 2010 election only served to reinforce their perceived importance with the introduction of three leaders’ debates. Thus, more than ever, an understanding of contemporary elections necessitates an understanding of the dimensions of leadership that matter most to voters. This contribution examines the influence of perceptions of the three major party leaders as responsive, trustworthy, and knowledgeable. It also examines how the debates and other events unfolding during the campaign served to structure these perceptions. There is evidence that voters’ evaluations of party leaders can vary substantially over the course of the campaign and traits such as responsiveness weigh heavily in voters’ assessments. There is also convincing evidence of media effects, suggesting that voters are receptive to events unfolding during the campaign.

Introduction

There is an increasing recognition of the importance of party leaders in British elections. While in the past social class was viewed as the major influence structuring support for parties (Butler & Stokes, 1974), economic and social changes in Britain have contributed to the erosion of traditional class cleavages. At the same time, the media’s emphasis on the personalities and activities of party leaders is seen to have contributed to the presidentialization of the office of British prime minister (McAllister, 2005; Mughan, 2000, 2005; Poguntke & Webb, 2005). According to Heffernan (2006, 582), ‘An interest in political celebrity, backed by an ever more prevalent interest in process journalism, magnifies the modern prime minister, placing him or her centre stage in key political processes.’ The 2010 election served to reinforce these trends. In particular, the introduction of three leaders’ debates in the three weeks before polling day lent the campaign a rhythm in which much of the discussion in the media involved an anticipation and dissection of debates. A large part of this discussion centred on the three major party leaders and the implications of their performances for their parties (Denver, 2010; Wring & Ward, 2010).

Campaign events such as political debates are assumed to play a prominent role in elections largely because voters’ preferences are less deeply rooted than in the past. Denver (2010: 591) confirms that almost 40% of voters in 2010 said that they decided which party to support during the campaign – and exposure to campaign communications of and about party leaders may play a key role in why campaigns matter. Thus, more than ever, an understanding of contemporary elections necessitates an understanding of how voters evaluate party leaders and how these evaluations are influenced by campaign events. In this contribution, we examine the character traits that mattered most to voters when evaluating the leaders of the three major parties in the 2010 British general election. We focus on traits such as knowledge, trustworthiness, and responsiveness and examine how exposure to the debates and party election broadcasts influenced perceptions of the party leaders. We then assess the relative importance of character traits on evaluations of the leaders and how those evaluations ultimately impact on vote choice.

Leadership Traits in British Elections

A number of studies have established that party leaders are highly visible figures about whom most voters have opinions (Clarke et al., 2004) and that leadership evaluations exhibit a strong and independent impact on party support (Clarke & Lebo, 2003; Clarke et al., 1998) and vote choice (Clarke et al., 2004; Evans & Andersen, 2005; Mughan, 2005; Stewart & Clarke, 1992).1

While there is little doubt that leaders now matter in Britain’s parliamentary system, it is not clear what voters care most about when it comes to party leaders (Bean & Mughan, 1989; Clarke et al., 2004, 2009; Evans & Andersen, 2005; Mughan, 2000, 2005; Stewart & Clarke, 1992). Early research on leadership traits in the United States incorporated the notion of ‘presidential prototypes’ against which presidents are judged (Kinder et al., 1980). Competence and trustworthiness emerged as ‘the preeminent traits for presidents and presidential hopefuls’ (Kinder, 1983: 1). Numerous studies since have both confirmed the influence of leadership traits in American elections and the centrality of competence and integrity (Bishin et al., 2006; Funk, 1996, 1997, 1999; Goren, 2002, 2007; Johnston et al., 2004). However, the influence of such considerations in Britain, let alone the extent to wh...