![]()

1

Referent Communication Disturbances in Schizophrenia

Bertram D. Cohen

Rutgers Medical School

Disturbances in the use of language are among the most convincing indications of a schizophrenic psychosis. Yet, as cryptic or disorganized as schizophrenic speech may sound, it rarely (if ever) includes hard instances of agrammatism or word-finding deficits. It is a disturbance of communication rather than of language per se; its most dependable feature is that listeners find the patient’s referents too elusive to grasp. Thus, measures of “communicability” are among the most effective discriminators of schizophrenic speech samples and are clearly superior to measures of style, structure, or thematic content (Salzinger, 1973). Accordingly, the emphasis in this paper is on disturbances of the referential process itself.

Putting the issue this way requires some understanding of the normal referent-communication process, one that can permit investigators to pinpoint components of the process as possible “loci” of schizophrenic disturbances. Therefore, basic to the work presented here is an empirically derived conception of how normal speakers select utterances to make it possible for their listeners to know what they are talking about and, also, how normal listeners use speakers’ utterances to identify their referents. Previous investigators in this field have rarely paid much attention to the need for an explicit conception of normal referent communication, perhaps because of the assumption that normal processes are so obvious that they can be taken for granted. To provide background for our own conception of normal and pathological referent communication, I first review briefly the major approaches to schizophrenic language and thought and the normal referent communication processes that they imply.

A productive place to start is Bleuler’s (1911) 65-year old analysis of schizophrenia as a cognitive disorder. Bleuler’s theory deals with “ideas” and “associations,” which were, of course, the popular concepts of eighteenth and nineteenth century psychology. Ideas were psychological representations of objects and events, and associations were the relational “threads” that connected ideas. For Bleuler, associations came in two main categories: logical and autistic. Bleuler believed that logical associations are the dominant forms of association in the normal adult. They occur more frequently than autistic associations and are, in effect, models of reality. Thus, if one’s associations are predominantly logical, one is not likely to combine ideas in a bizarre, delusional, or incoherent manner. Autistic associations, in contrast, give rise to combinations of ideas that are likely to be analytically or empirically false. For Bleuler’s normal adult, autistic associations, in effect, are held in check by logical associations and intrude into thought-and through thought into speech-only during moments of high emotional stress. With the onset of schizophrenia, the single crucial change was, for Bleuler, the “loosening” of the associations, a psychopathological process that he assumed to attack principally the logical associations, with the result that the autistic associations are permitted freer access to expression.

Bleuler’s theory can be viewed either as a hierarchic model or as a control model As the hierarchic model, the emphasis is on changes in the schizophrenic speaker’s hierarchically ordered repertoire of associations in which the relative strengths of autistic associations have been increased. From the control viewpoint, the emphasis is instead on the schizophrenic speakers’ loss of organizational control of their thought processes; that is, the loosening of the logical associations diminishes the speaker’s power to control associative selection. Under these conditions, one’s thoughts become autistic in the sense that they are determined by fortuitous contiguities in experience or by partial or inessential similarities among ideas. It is important to note that the control model permits the same associations to be logical in one context but autistic in another. The control model emphasizes failure in a mechanism that selects contextually appropriate associations; the hierarchic model emphasizes pathological changes in the repertoire itself.

Contemporary “interference theories” (Buss, 1966) of schizophrenic deficit appear to be of the hierarchic type. These twentieth century conceptions speak of “responses” in place of ideas, and associations are seen as relations among responses (or between responses and stimuli). Broen and Storms (1966), for example, proposed a theory in which responses that are, for the normal adult, low in frequency of occurrence and contextually inappropriate accrue larger relative strengths in the associative repertoires of schizophrenic patients. Therefore, they are more likely to intrude into thought and language.

A difficulty with such hierarchic theories is that they equate the appropriateness of a given association with its relative dominance in the associative repertoire from which it is selected. Such a theory would require the normal adult to possess as many repertoires as there are contexts if he were to speak or think “appropriately.” Aside from questions of parsimony, this type of conception also fails to consider the large diversity of situations in which an unusual association to a referent is not only recognized (by nonschizophrenics) as appropriate but even as astute, witty or creative.

In contrast to the Broen-Storms theory is the Chapmans’ (1973) dominant-response hypothesis. Whereas the Broen-Storms theory views schizophrenic performance in terms of the increased strengths of normally weak responses, the Chapmans view the schizophrenic patient as someone whose verbal behavior is unduly influenced by what are normally the strongest responses in his associative repertoire. This type of interference-by-dominant-associations conception is reminiscent of the theory proposed 35 years earlier by Kurt Goldstein (1944), in which schizophrenic “concreteness” was seen as an inability to shift one’s attention from some single, salient feature of a referent object regardless of that feature’s pertinence to the context in which it was perceived or communicated.

The Chapman and Goldstein theories are variations on a control model in the sense that they posit deficits in the patient’s ability to resist interference from strong but inappropriate associations, meanings or descriptions of a referent object. Presumably, normal adults are able to neutralize the power of such salient or dominant responses to scan their repertoires for responses that are more pertinent to the momentary context. How do normals manage this? These theories may specify a normal outcome but are silent about the process through which this outcome is achieved.

Sullivan (1944) is relatively unique among theorists in this field because, although lacking precision and detail, he did explicitly propose a conception of the normal speaker’s referential process and then attempted to explain schizophrenic communication in terms of certain disturbances in the normal process. He postulated a self-editing process whereby normal speakers pretest their utterances against an implicit “fantastic auditor” before saying them aloud to listeners. Insofar as this inner listener is an accurate representation of the speaker’s real listener, the pretest helps the speaker edit out utterances that may prove too cryptic, misleading, or unacceptable to an actual listener. Schizophrenic speech, according to Sullivan, occurs either when the speaker fails to pretest utterances altogether or pretests them against an invalid fantastic auditor, that is, one that fails to represent the actual listener realistically.

Though brief, I hope my reference to Bleuler and more recent investigators highlights the two principal ways in which disorders of referent communication are explained: disorders in the speaker’s repertoire of associations, meanings, or descriptions of a referent, and disorders in the selection mechanism through which the speaker edits out contextually inappropriate (cryptic, ambiguous, or misleading) responses before they intrude into overt speech.

In the following sections I (1) describe and illustrate an experimental paradigm for studying referent communication; (2) outline a theoretical model that accounts for behavior in these experimental situations and incorporates both repertoire and selection (self-editing) components; (3) examine a number of studies designed to analyze schizophrenic speaker disturbances in terms of the model; and (4) consider implications of the data and theory for the psycho-pathology and treatment of these disturbances.

Experimental Paradigm

The basic experimental situation has involved the presentation of an explicit set of stimulus objects to a speaker with one of the objects designated as his referent. The speaker’s task is to provide a verbal response so that his listener can pick out the referent from the set of objects. The listener’s task is to identify the referent from the stimulus set on the basis of the speaker’s response.

In early studies (Rosenberg & Cohen, 1964) words were used as the referent and nonreferent objects. A speaker was shown pairs of words and was instructed to provide a third word, one that neither looked nor sounded like either of the words in the stimulus pair, as a “clue” (referent response) for a listener. Although artificial, this use of single-word responses and single-word referent stimuli permitted investigators to take advantage of word-association norms to estimate certain quantitative properties of the associative repertoires from which speakers selected responses in this situation. It should be clear, however, that the use of the paradigm was limited neither to verbal stimuli nor to single-word speaker responses. Later studies involved nonverbal referent objects and speakers’ responses that consisted of continuous discourse.

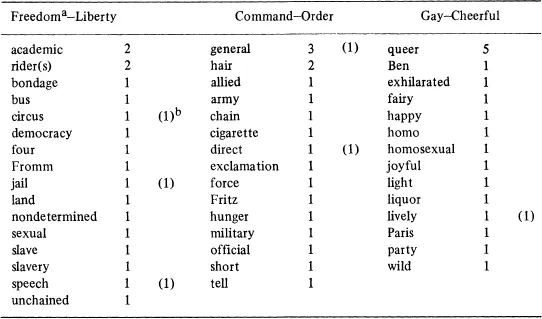

The data shown in Table 1.1 were obtained in an early exploratory application of the paradigm with 18 speaker–listener pairs. This table includes the speaker-response distributions from three word pairs. For any given word pair, the speaker provided a clue word for a listener who was seated facing away from him in the same room. In each instance, the speaker was shown the word pair with the referent word underlined, and the listener was shown the same word pair with neither word underlined. The listener’s task was to indicate to the experimenter, by pointing, a choice of the referent after hearing the speaker’s response.

Table 1.1

Speaker-Response Frequencies and Listener Errors in Sample Protocols from Eighteen Speaker-Listener Pairs (Word-Communication Task)

aThe first word in each pair was the referent.

bThe number of responses that led to listener errors are shown in parentheses.

(From Cohen, 1976. Reprinted with permission of the New York Academy of Sciences.)

Synonym pairs were found to be especially instructive because many of the responses associated with the referent in such word pairs were likely to overlap with responses to the nonreferent thus accentuating a contextual factor that the speaker had to confront if he or she was to communicate effectively, that is, if the subject was to avoid “overincluding” the nonreferent. The distributions of speakers’ responses shown in this table are representative of results obtained for pairs of synonyms.

The content of many of the responses to these high-overlap word pairs reflects the speaker’s specific relationship to the listener. That is, speakers and listeners were self-selected pairs (in this pilot study– from the same college subculture, geographical region, and era, which may have made possible the effective use of such responses as academic and riders to FREEDOM: or queer to the referent GAY, a pejoratively toned association that would surely be less evident among similar college students today. Other more individualized examples are the response Fromm to FREEDOM by a speaker who was, at that time, enrolled in the same Psychology of Personality course as her listener and the response Fritz to COMMAND by a speaker who belonged to the same fraternity as his listener, a fraternity whi...