![]()

PART

I

INTRODUCTORY OVERVIEW

![]()

CHAPTER

1

Toward the Improvement of

Training in Foreign Languages

Alice F. Healy and Immanuel Barshi

University of Colorado, Boulder

Robert J. Crutcher

University of Illinois, Chicago

Liang Tao, Timothy C. Rickard, William R. Marmie,

Vivian I. Schneider, Andrea Feldman, Carolyn J. Buck-Gengler,

Stephen G. Romero, Nancy B. Sherrod, James T. Parker,

and Lyle E. Bourne, Jr.

University of Colorado, Boulder

ABSTRACT

This chapter summarizes some of the studies in a research program aimed to identify and to develop psychological principles for improving training in foreign languages. These studies shed light on the following five issues: (1) To what extent does a person adopt or adapt first-language strategies in the acquisition and use of a second language? (2) What are the best methods for efficient and durable acquisition of vocabulary items in a foreign language? (3) What role do abstract linguistic categories play in the acquisition of language skill and the day-to-day use of language? (4) What are the functional units of a language and how do they differ for native and nonnative speakers? (5) How do knowledge of the language and utterance complexity interact to determine message comprehensibility for a listener?

Our lives are increasingly international and multilingual. It is imperative, therefore, that substantial segments of our population have a working command of the languages of those individuals with whom they need to interact and communicate. Foreign language training programs have been developed to meet this need.

It is possible to structure language training in a variety of ways. At one extreme is training that focuses on the abstract grammar underlying an ideal speaker's knowledge of the language. This course would be designed to promote the acquisition of formal linguistic principles that describe the structure of language. Consider, for example, the rules for pluralizing English nouns. One such rule refers to the distinctive phonetic feature of voicing. Specifically, correct pronunciation requires voicing assimilation, or an agreement in voicing, between the final consonant of the root noun and the plural morpheme. A language course could be organized around such principles, and indeed this is the standard practice in many educational settings. At the other extreme is training that focuses on the psychological principles that influence a real speaker's comprehension and production of the language. This course would be designed to promote the acquisition and use of pragmatic psycholinguistic principles. For example, experiments by Healy and Levitt (1980) show that naïve individuals do not have access to the concept of voicing, although they can easily learn a phonological rule based on voicing assimilation if it coincides with ease of pronunciation. A language course could be organized around such principles; however, at present a course based primarily on psychological principles has not been realized. It has been the ultimate goal of our research project to identify a set of psychological principles that can provide the foundation for (or, at least, augmentation of) a foreign language training course.

It would be unrealistic to expect that in one limited project we could address the full range of psychological principles that such a course requires. Our goal has been more modest. Nevertheless, we have investigated a wide range of potentially valuable psycholinguistic issues relevant to language training. Among the issues of greatest concern to us have been: the extent to which a person adopts or adapts first-language strategies in the acquisition and use of a second language, the best methods for efficient and durable acquisition of vocabulary items in a foreign language, the role abstract linguistic categories play in the acquisition of language skill and the day-to-day use of language, the functional units of a language and how they differ for native and nonnative speakers, and how knowledge of the language and utterance complexity interact to determine message comprehensibility for a listener.

Overriding these questions is a fundamental interest in designing optimal training programs. We define optimality in terms of three characteristics: Minimize the time to reach a criterion level of performance, ensure the long-term retention of the acquired knowledge and skills that underlie performance, and provide for maximal transfer of what has been learned from the training context to other environments. Our research (see Healy & Bourne, 1995, for a summary) underlines the importance of all three of these criteria. For example, we have discovered that training that minimizes acquisition time may, in fact, be detrimental to long-term retention. Likewise, in other studies, we have found that training that maximizes long-term retention may severely limit the transferability of that material. It is thus vitally important that all three characteristics of on-the-job performance be considered to establish the validity of an instructional program.

Our project has addressed both first- and second-language learning and use. In some studies, we employed subjects of varying degrees of fluency in the second language, expecting that the degree of fluency would have an important impact on the relevant psychological processes. In other studies, we focused exclusively on performance in the first language because we were convinced that understanding the psychological processes underlying first-language use would yield valuable insights into the optimal methods for training in any other language.

We have made considerable progress on a number of issues. In this chapter, we review some of our most important findings (see the following chapters for a more detailed discussion of several of these studies).

TRANSFER OF STRATEGIES FROM FIRST

TO SECOND LANGUAGE

The first issue we discuss concerns first-language strategies in second-language use. In earlier work (Tao & Healy, 1996a), we tested two related hypotheses concerning the connection between language and cognition from a linguistic perspective. The first hypothesis is that the structure of a particular language elicits unique strategies that speakers utilize to process discourse information. We refer to this as the language-specific strategies hypothesis. The second hypothesis is that the strategies formed as a result of the native language structure are likely to influence speakers when they process discourse information in a nonnative language. We call this the strategies transfer hypothesis. Our experiments tested these related hypotheses specifically on the different cognitive strategies that speakers of English and Chinese use to track references in discourse.

One of the major differences between English and Chinese is that Chinese relies much more on the use of zero anaphora, which is an empty grammatical slot in a sentence that in English is usually filled with a noun phrase or a pronoun. For example, consider the English sentence, Hillary Clinton went to Boulder, and the first lady spoke to CU students. The first lady is a noun phrase that refers to Hillary Clinton. This noun phrase could be replaced by the pronoun she, as in the sentence, Hillary Clinton went to Boulder, and she spoke to CU students. Alternatively, it could be replaced by an empty slot, which is known as zero anaphora, as in the sentence, Hillary Clinton went to Boulder and spoke to CU students. Although, as is clear from this example, English makes some use of zero anaphora, this device is much more commonly used in Chinese.

Earlier, we conducted three experiments that tested native English and native Chinese speakers on their ability to tackle zero anaphora in English passages (Tao & Healy, 1996a). We employed three different types of passages. In the first type (full form), no elements were missing. In the second type (missing noun phrase), there were missing nominals corresponding to zero anaphora in Chinese. In the third type (missing modifier), there were missing modifiers in noun phrases, creating ambiguous anaphoric references. Subjects were given discourse passages with missing elements, but there was no indication that any words were missing (e.g., there were no blank spaces). Subjects were instructed to read each passage once and then to give a comprehensibility rating to the passage.

The results of the three experiments revealed that, although the passages were in English, native Chinese speakers gave significantly higher comprehension ratings to the passages with missing noun phrases and missing modifiers than did native English speakers. In contrast, the two groups did not significantly differ in their comprehension ratings for the full form passages.

In two of the experiments, subjects were also given a fill-in-the-blank test, in which missing elements were indicated in the passages by blank spaces. Subjects were asked to fill in the missing words along with a confidence rating for each choice. On this task we found no disadvantage for the native English speakers, suggesting that they have the ability to track the missing referents although they may not invoke that ability when there is no explicit indication of a missing word.

The three experiments provided strong evidence supporting both the language-specific strategies hypothesis and the strategies transfer hypothesis. The experiments demonstrated that the native English speakers, although capable of tracking missing referents in a discourse, had more difficulty processing discourse information than did the native Chinese speakers when there were many instances of zero anaphora in the discourse.

In two more recently completed experiments (Tao & Healy, chap. 8, this volume), we examined two new subject groups. In Experiment 1, we compared native English speakers and native Chinese speakers to native speakers of Dutch, a language related to English that also has infrequent zero anaphora. In Experiment 2, we compared native English speakers to native speakers of Japanese, a language that has frequent zero anaphora, as does Chinese. We expected to find the native Dutch speakers' performance similar to that of the native English speakers and the native Japanese speakers' performance similar to that of the native Chinese speakers. Both experiments yielded evidence supporting these predictions.

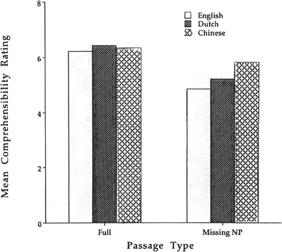

In Experiment 1, subjects were given the comprehension rating task with both missing noun phrase and full form passages. The results are summarized

FIG. 1.1. Mean comprehensibility rating for native English speakers, native Dutch speakers, and native Chinese speakers as a function of passage type in Experiment 1 by Tao and Healy (chap. 8, this volume). NP = noun phrase.

in Fig. 1.1. The native Dutch speakers showed a pattern of results much closer to that of the native English speakers than to that of the native Chinese speakers. Note in particular that the Chinese subjects gave somewhat lower comprehension ratings to the full form passages than did the Dutch subjects, but the Chinese subjects gave much higher comprehension ratings to the missing noun phrase passages than did the Dutch subjects.

In Experiment 2, subjects were given both the comprehension rating task and the fill-in-the-blank test with both missing noun phrase and missing modifier passages. The results are summarized in Fig. 1.2. For both passages, the native Japanese speakers gave somew...