![]()

Part I

Introduction

![]()

1 | An overview of mild cognitive impairment |

| Holly A. Tuokko and Ian McDowell |

The aim of this book is to provide a comprehensive examination, from multiple perspectives, of the concept of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) in old age. As interest in MCI has grown, the utility of the concept has been investigated in both clinical and population-based samples in many countries. Findings have varied widely. Although the differences observed between samples may reflect “legitimate variations” (Petersen & Morris, 2003), there has been little attempt to integrate what we have learned about MCI from each of these perspectives. This book aims to summarize the current understanding of MCI, to identify key findings and technical issues arising from the study of MCI, and to propose future directions for research. This introductory chapter provides an overview of the evolving conceptions of cognitive change in later life. Empirical studies of MCI are summarized and methodological issues influencing this research are then discussed. Finally, we review the implications of different conceptions of MCI for interventions. Subsequent chapters present perspectives on MCI taken by researchers around the world. In the final chapter of the book, we summarize findings from these various perspectives and highlight promising areas for future research.

Overview of the evolving conceptions of cognitive change in later life

It has long been recognized that while changes in memory are a normal part of aging, some forms of memory change may indicate an underlying neurodegenerative disease (Kral, 1962). It is this latter, abnormal, form of memory change that has stimulated the interest of clinicians and researchers in anticipation of the universal rise in the proportion of the population that will live well beyond 65 years of age. Age-associated neurodegenerative disorders of cognitive function such as Alzheimer's disease (AD) and vascular forms of dementia (VaD) produce devastating effects on the patient, their family, and society. Over the past 25 years, many studies have described the impact of these disorders; more modest advances have been made in developing interventions to slow or delay their progression. With the prospect of increasingly effective interventions, however, attention has focused on early identification of cognitive disorders under the assumption that earlier intervention will lead to better outcomes.

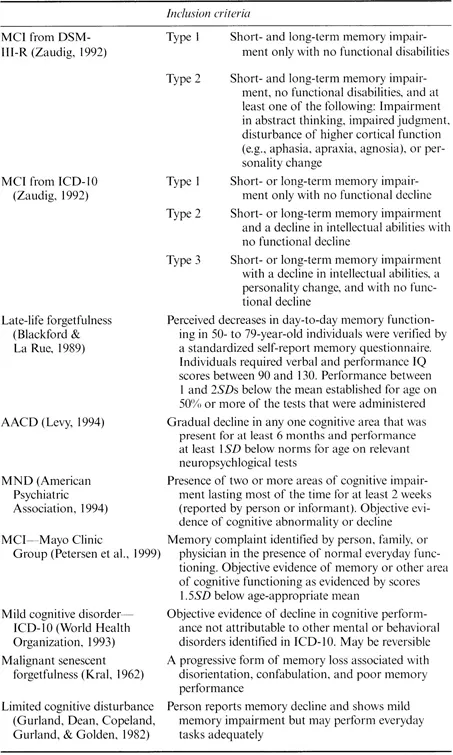

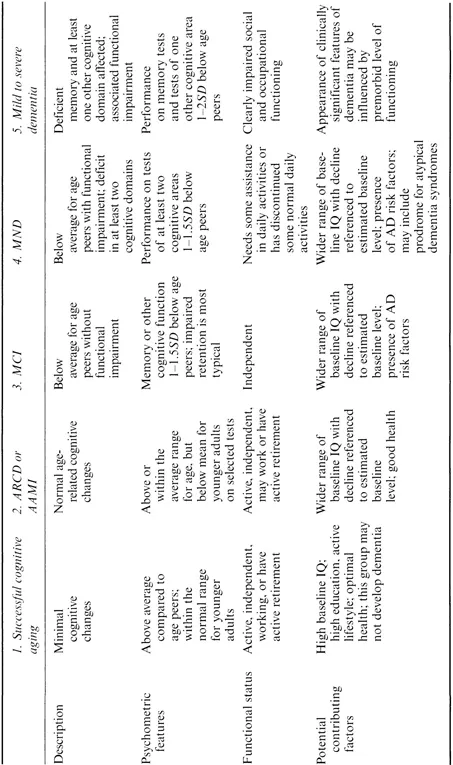

Attempts to identify those at risk of developing dementia have led to many proposals for ways to classify milder late life cognitive impairment— impairment that is insufficient to warrant a diagnosis of dementia. The early classifications were dichotomous, postulating the existence of discrete categories of normal and pathological aging. For example, Kral (1962) proposed the terms benign and malignant senescent forgetfulness to describe forms of cognitive decline distinguishable on the basis of symptoms, course, and prognosis. As more and more terms and classifications were introduced (Table 1.1), it was initially unclear which were intended merely to describe presenting cognitive symptoms and which carried implications regarding underlying pathology and eventual outcome. In several of the more recent classifications, however, formal sets of criteria were introduced and their links to pathology and eventual outcome were made explicit. In an attempt to integrate the various approaches for categorizing early cognitive decline, Rediess and Caine (1996) arrayed them along a spectrum of function from optimal cognitive aging through dementia. Rediess and Caine identified five broad clusters in the spectrum of cognitive function (Table 1.2), including (1) successful or optimal cognitive aging; (2) age-related cognitive decline (ARCD; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) or age-associated memory impairment (AAMI; Crook, Bartus, Ferris, Whitehouse, Cohen, & Gershon, 1986); (3) age-associated cognitive decline (AACD; Levy, 1994) and MCI (Smith, Petersen, Parisi, & Ivnik, 1996; Zaudig, 1992); (4) questionable dementia and mild neurocognitive disorder (MND; American Psychiatric Association, 1994); and (5) dementia (ranging from mild to severe). Differences along this spectrum of cognitive function are viewed as quantitative in nature with a substantial overlap between stages in terms of both biological and psychological variables (Brayne & Calloway, 1988; Von Dras & Blumenthal, 1992). Cluster 2 includes people with subjective cognitive complaints and/or age-consistent cognitive function where decline is not necessarily anticipated: their cognition is on a plateau. In contrast, Clusters 3 and 4 exhibit objective evidence of cognitive impairment and form a heterogeneous group, including people who have always occupied the lower end of the normal distribution in terms of memory performance as well as those considered likely to progress to dementia over time. We shall here apply the term “MCI” in a generic sense to identify these groups, and extend it to include people identified with MCI by specific criteria such as those developed at the Mayo Clinic (Petersen, Smith, Waring, Ivnik, Tangalos, & Kokmen, 1999; Smith et al., 1996), or by Zaudig (1992).

With so many options and uncertainties in the definition of MCI, it is not surprising that many rival approaches have been proposed. None of the approaches identified in Table 1.1 is generally accepted or consistently applied in the research literature, and the collection of empirical evidence on their

Table 1.1 Some terms and definitional criteria sets used to describe cognitive impairment not sufficient to meet criteria for dementia

Table 1.2 Spectrum of cognitive functioning in later life

Source: Modified from Rediess and Caine (1996)

predictive validity for identifying future progression to dementia faces a variety of methodological challenges. These contribute to uncertainty in establishing basic estimates of the incidence, prevalence, and speed of cognitive decline.

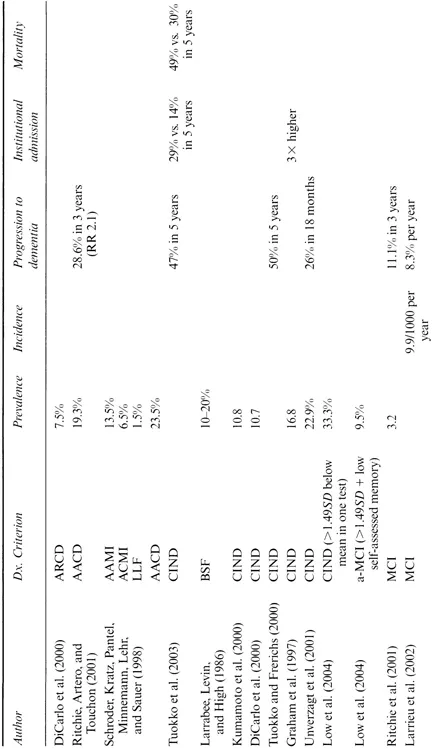

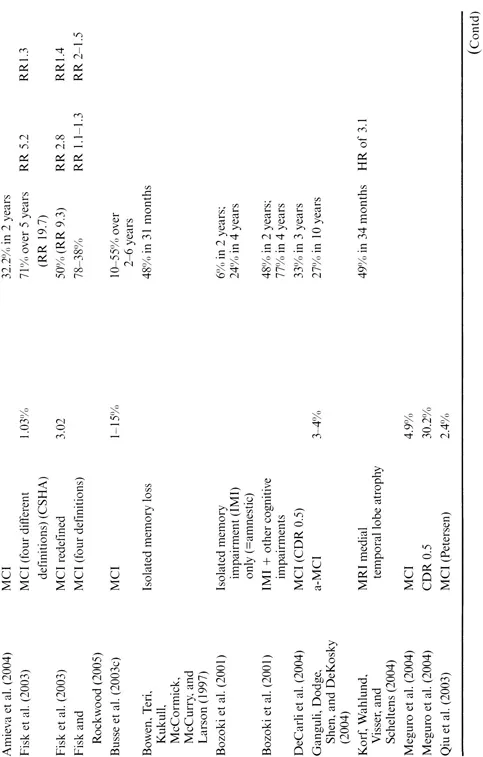

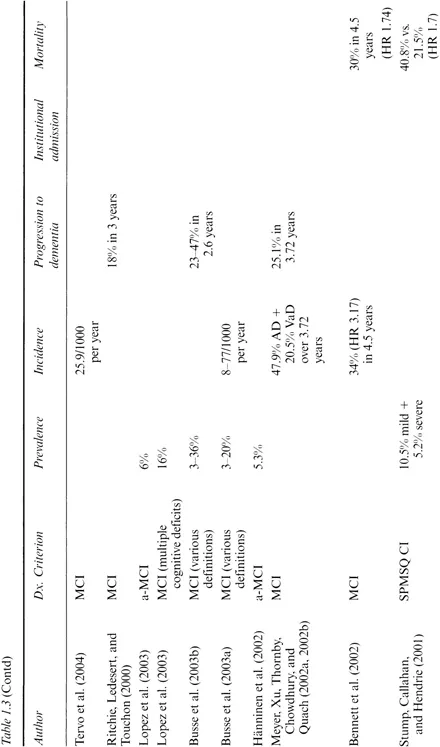

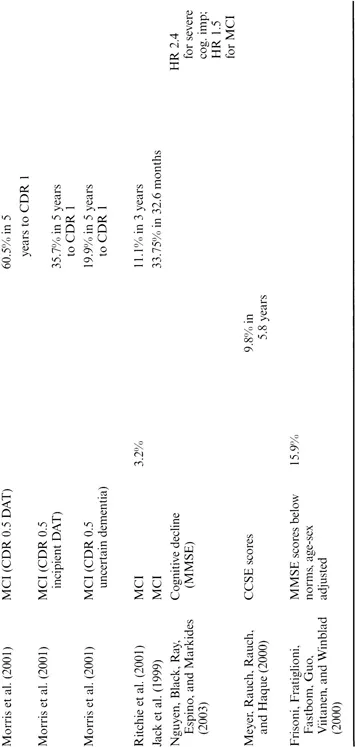

Empirical evidence concerning the prevalence of MCI and conversion to dementia

Virtually all commentators have noted the wide variation in estimates of the prevalence of early cognitive impairment (Bischkopf, Busse, & Angermeyer, 2002; Jonker, Geerlings, & Schmand, 2000; Luis, Loewenstein, Acevedo, Barker, & Duara, 2003). That there is variation between different syndromes, such as AAMI and MCI (Table 1.3), need not surprise us. However, there is also wide variation among prevalence estimates of apparently the same condition. Busse et al., for example, quoted figures for the prevalence of osten sibly the same definition of MCI ranging from 1 to 15% (Busse, Bischkopf, Riedel-Heller, & Angermeyer, 2003c); other estimates rise to over 30% (Busse, Bischkopf, Riedel-Heller, & Angermeyer, 2003a, 2003b).

Correspondingly, there is a wide variation in conversion rates from cognitive impairment to dementia. Bischkopf's review of 26 studies (Bischkopf et al., 2002) and Palmer's review of 17 (Palmer, Fratiglioni, & Winblad, 2003) showed annual conversion ranging from 1 to over 40%, varying by sample, diagnostic criterion, and severity of impairment. The majority of studies, however, report conversion rates between 10 and 20% per annum (Petersen, Stevens, Ganguli, Tangalos, Cummings, & DeKosky, 2001), although some findings are clearly higher. Flicker, for example, found about 72% conversion over 2 years, or 36% over 1 year (Flicker, Ferris, & Reisberg, 1991). To develop a mathematical model, Yesavage, O'Hara, Kraemer, Noda, Taylor, and Ferris (2002) needed to choose a representative conversion rate from MCI to AD, and they selected 10% per year, regardless of age.

Accounting for the variations

Some of the variation in estimates of prevalence and conversion merely reflects different ways of presenting the results. Some studies, for example, report crude conversion rates while others adjust for variables such as age or education, which helps to correct for demographic differences in the samples. Comparisons are also made difficult as the statistic used varies according to study design: case-control studies typically report relative odds of conversion (Bennett et al., 2002), while longitudinal studies report percentages converting to dementia (Petersen et al., 2001). Because the time period for longitudinal studies varies, results are often averaged to an annual rate. However, it may be difficult to compare conversion rates based on different time periods, as longer studies tend to suffer greater attrition, and those lost to follow-up have greater cognitive impairment (Hänninen, Hallikainen, Tuomainen, Vanhanen, & Soininen, 2002).

Table 1.3 Studies of early cognitive impairment, showing prevalence, incidence, and rates of conversion to dementia

Note: AACD. age-associated cognitive decline; AAMI, age-associated memory impairment; ACMI, age-consistent memory impairment; AD. Alzheimer's discase; a-MCI, amnestic MCI; ARCD. age-related cognitive decline; BSF, benign senescent forgetfulness; CCSE, Cognitive Capacity Screening Examination; CDR. Clinical Dementia Rating scale; CIND, cognitive impairment with no dementia; CSHA. Canadian Study of Health and Aging; DAT, dementia of the Alzheimer's type; HR, hazard ratio; LLF, late-life forgetfulness; MCI, mild cognitive impairment; MMSE. Mini-Mental State Examination; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; RR, relative risk; SPMSQ CI, short portable mental status questionnaire defined cognitive impairment; VaD, vascular dementia.

It is self-evident that the way cognitive impairment is defined will affect prevalence and rates of conversion, but factors such as study design and the sample can also affect results. The choice of definition and study design reflects the implicit model of the natural history of cognitive decline that underlies the study and this can also affect the findings. These sources of variation will be discussed in turn.

The operational definition of MCI

Collie and Maruff (2002) listed 17 different classifications of early cognitive impairment, yet their list is not complete. Divergences between the classifications include questions such as whether both objective and subjective memory problems are required, whether or not evidence for decline is required as opposed to merely impairment, whether or not other deficits beyond memory are required, and whether or not impairments in daily function are considered in the definition. Even minor differences in classification systems can exert large effects on the results (Morris et al., 2001). For example, Fisk, Merry, and Rockwood (2003) showed that removing the requirement for subjective memory complaints doubled the prevalence estimate. And, the definition of subjective memory complaints is variable: it can refer to a spontaneous comment during the clinical examination, or can be based on a formal interview (Jonker et al., 2000).

Most recently, it has been proposed that there are several clinical subtypes of MCI: amnestic MCI (a-MCI), single nonmemory domain MCI (sd-MCI), and multiple domains MCI (md-MCI). The latter can occur with memory impairment (md-MCI + a) or without (md-MCI – a) (Petersen, 2004b). These clinical subtypes may reflect distinct etiologies and vice versa. For example, a-MCI may represent a prodromal form of AD or may be related to depression; a-MCI and md-MCI + a both have a high likelihood of progressing to AD. Those subtypes affecting primarily nonmemory cognitive domains, such as executive functions and visuospatial skills, are thought to reflect the pathology of non-AD dementias such as Lewy body or frontotemporal forms.

Whatever subtypes are specified, there are three basic approaches to operationally defining MCI: norm-based, criterion-based, and via clinical judgment. Norm-based definitions classify the individual's performance relative to a known distribution of scores, such as defining scores ≥ 1.5SZ) below the mean of a cognitively normal sample as being impaired. This approach corresponds to the assumption of a single continuum of cognition, with impaired people showing quantitative differences rather than differences of kind. Hence, a purely statistical criterion is appropriate, with the choice of a particular threshold (e.g., 1.55D) determined empirically. An advantage to this approach is that no matter how difficult the memory test is, roughly the same number of people will be identified. The disadvantage is that there will almost always be an overlap in scores between the normal population and the group with cognitive impairment. If the distribution is based on a normal sample, roughly 7% of the normal population will fall below -1.5SD and be falsely classified as impaired. It is also meaningless to use this approach in estimating prevalence: the choice of cutting-point in terms of standard deviations will largely determine the prevalence of MCI obtained.

Alternatively, MCI can be defined via a criterion, either by selecting a particular score on a reference test to designate a “significant” impairment, or in terms of a level of cognitive impairment that corresponds to a handicap such as not being able to live independently. The criterion approach has the advantage of permitting a fair assessment of prevalence, but of course this will vary according to the (essentially arbitrary) criterion used, as seen in Table 1.3. Furthermore, the problem lies in deciding what test to use as the criterion, and whether the criterion threshold should be constant for all groups. If the criterion threshold is adjusted for age, the absolute criterion is effectively turned into a relative one (Hänninen et al., 2002). Ultimately, both the norm-and criterion-based approaches are arbitrary: why 1 or 1.5SD, and why choose a particular test as the defining criterion?

The idea of using an external criterion, such as living independently, seems conceptually relevant but may be impractical owing to the insensitivity of standard instrumental activities of daily living (IAD...