![]()

1

Introduction

This book is mostly about unconscious conspiracies by poor African American girls and their mothers to promote daughters’ unwed adolescent pregnancies and motherhood. It is also about mother-daughter dyads from the same population who conspire to promote a different outcome for daughters—one in which pregnancy and childbirth are delayed beyond adolescence and occur in the context of marriage. In the background of both conspiracies are men—fathers, boyfriends, and husbands—who, whether actually present in women’s lives or not, set the stage for the kinds of interpersonal and intrapsychic relationships that mothers and daughters forge with one another and, as a consequence, for the ultimate outcomes of daughters’ adolescent sexual activities.

The idea that adolescent pregnancy is a problem to be studied originated with the poor, African American women living in a sugarcane-growing region of southern Louisiana known as the River Parishes. I first visited this region in 1985 with Henry Reiff, then a graduate student in special education, with the goal of finding a naturalistic setting in which to study the development of moral concepts in children. To enlist families for our study, Henry and I distributed flyers to people’s houses announcing that we were university teachers interested in studying how children learn right from wrong and that we would be willing to tutor children having trouble in school in exchange for being able to spend a few hours per week observing their day-to-day interactions with peers and adults. Several families responded with interest, and we made arrangements to start right away.

It quickly became apparent that the women we talked to were less interested in having their children tutored or in how children learn right from wrong than in the more immediate problem of how poor they were and how they felt unable to raise themselves up out of this dismal economic situation. We became intrigued by what seemed to be a clear contradiction between women’s stated beliefs that adolescent pregnancy is detrimental to economic advancement and their behavior of continuing this pattern of childbirth. After a few months, we had turned our attention away from the study of moral concept development to the question of why girls in this community continue to become pregnant as unwed adolescents.1

From the conscious perspectives of women who had become mothers as adolescents, adolescent pregnancies were unwanted. They had “just happened,” had happened because of ignorance about how babies are conceived, or had happened because methods for preventing or aborting pregnancies were either unknown or inaccessible. One older woman recounted how, as a 14-year-old girl, she walked past the house of an older man (in his 30s) every day on her way to school. After a while, they started “talking,” and one thing led to another. When she realized she was pregnant, she told her friends, and they said “Oooh, your Mama’s gonna kill you.” To avert this calamity, she drank an entire bottle of castor oil, hoping this would abort the fetus. Although she knew about other methods of “throwing babies away” (a concoction she called “Blue Stone” and the services of midwives), neither of these seemed immediately accessible; she had heard of Blue Stone but did not know where to get it and did not want to ask, and the midwives lived on the other side of town. Inadvertently, the empty bottle of castor oil was left lying out where Mama could find it. Mama did find it, and in a predicted rage, banished the daughter to her older sister’s house for several months. The story had a happy ending, however, with mother relenting and agreeing to raise the baby and daughter eventually meeting and marrying a man with whom she lived for the rest of her life.

The baby, in the meantime, grew up to become an unwed adolescent mother at age 15. Her story was of meeting a man while out walking with her friends. They started “talking,” and again, one thing led to another. When she first told us her story, this woman insisted that when she was a teenager, she thought babies came down the river by barge and that she had been completely taken by surprise when her own first baby arrived by a different venue. A few years later, however, when reminded of this belief, she recanted and admitted just telling us this because she thought that was what we wanted to hear. Her real reason for becoming pregnant, she said then, was because she was ready to have a baby.

We were skeptical about these conscious theories of former adolescent mothers. On the one hand, although we believed that women believed that adolescent pregnancies had “just happened” as they described, we also believed that behavior that seems to have just happened always has multiple motivational sources. Although these motives may not be consciously known by the persons involved, the goal of research is to discover and describe them.

We were just as skeptical of the idea that the younger women in this community do not know how babies are made or how the making of babies can be prevented. Although the older women we talked to were teenagers before the days of school-based health education programs or widespread availability of birth control, this was clearly not the case for the younger women, who for the most part had become adolescent mothers within the last decade. As we were to learn later in the study, the public schools and health clinics in the River Parishes have been active for at least a decade in promoting sex (health) education and the accessibility of contraceptives. Movies and pamphlets about sex, pregnancy, and contraceptives are routine components of health education programs beginning in fifth grade; health clinics are conveniently located near schools; and the schools grant permission for students to leave campus during school hours for visits to the clinic.

Further, even small children we talked to had some knowledge about sex, how babies are made, and birth control—ideas they uninhibitedly shared. One 4½-year-old girl I tutored in the beginning of our study, for example, invited me in our first session to inspect the little white pills her mother kept in the refrigerator that stopped her from having babies and that made her “tizzies” get big. Six- and 7-year-old boys whom we “interviewed” in the context of our moral development study told stories about “bad” men who “messed with” their sisters and who should therefore be arrested and put in jail for life. These spontaneous comments, we thought, revealed a normal childhood interest in babies and sex and an environment in which open discussion of such matters is allowed. Under these circumstances, we thought it unlikely that older girls and women were ignorant about sex and pregnancy.

Our own theories, meanwhile, were developing along different lines. One very powerful motive for unwed adolescents’ pregnancies in this community, we hypothesized, might have to do with tradition. Many girls getting pregnant as adolescents in this community, it seemed, were doing what their ancestors in precolonial West Africa had done; what their slave ancestors who lived and worked the same plantations in this region had done; and more immediately, what their older sisters, mothers, grandmothers, and great-grandmothers had done. Most immediately, adolescents getting pregnant in this community were doing what many other girls in their peer group were doing. With this tradition behind and around them, what else could girls do?

A second possible motive, we thought, might have to do with how poor these families were. Although most teens and young adults had completed or were in the process of completing their high school educations or G.E.D.s (Graduation Equivalency Degrees), going to college cost money they did not have. Jobs in this region for poor African American men or women, regardless of whether they had a diploma, were few and far between. Moreover, for reasons that were unclear at the time, job prospects that did materialize always seemed to fall through. Survival in this environment of limited prospects seemed to depend on the social and economic support provided by kin and extra-kin networks. Because it seemed clear from our initial observations that babies of unwed mothers were a focal point of networking activities, we surmised that adolescent pregnancies might play a role in keeping these networks together. What that role might be remained to be seen.

A third possible reason why girls get pregnant in this community, we suspected, might have to do with their mothers. On an interpersonal front, mothers’ emotional and verbal reactions to daughters’ entrances into puberty were so forceful and intense that, although the mothers explicitly encouraged daughters to abstain from sexual activity, the reactions seemed to have the opposite effect. These patterns of actions and reactions by mothers and daughters, moreover, were “scripted” in that they seemed to recur in standard form among mother-daughter dyads throughout the community. We speculated that these standard scripts have developed over historical time in this population and are learned anew by successive generations of adolescent girls through interactions with mothers. On an intrapsychic front, the stories that both mothers and daughters told suggested that becoming pregnant and bearing a child as an unwed adolescent served some unconscious purposes for the mother-daughter relationship. It seemed, therefore, that mothers, having one foot in the sociocultural and the other in the psychological-developmental compartments of daughters’ internal representational worlds, must play a key role in daughters’ adolescent pregnancies.

At the same time, however, there were older women, younger women, and girls in this community who had not become or were not currently pregnant as adolescents. These women had the same ancestry, were just as poor, and seemed to live in the same kinds of family environments as women who had become adolescent mothers. Moreover, not all daughters talked about or interacted with their mothers in the same way. The task of understanding why some adolescent girls get pregnant and others do not; how to sort out these possible reasons; and once sorted, how to fit them back together in some coherent framework soon became our central goal.

The specific questions we had in mind at this initial juncture, then, had to do with both sociocultural and psychological-developmental motives for adolescent pregnancies among poor, unwed African Americans. What are the cultural motives? What are the psychological motives? Are both kinds of motives important, or does one category supersede the other? How can we assess cultural and psychological motives, especially if the people themselves are not consciously aware of them? If both kinds of motives are important, how can we understand the relations among them? Can an understanding of these relations in the present day help us to understand how the adolescent pregnancy system in this population has changed and is changing?

In addressing these questions throughout this research, I bring to bear a set of diverse psychological and anthropological theoretical perspectives that, in one form or another, are concerned with the interplay in complex systems of human behavior between psychological and cultural motivations. These theoretical perspectives differ, among other ways, with respect to the degree to which cultural and psychological motives are granted separate reality status and with respect to their conceptualizations of relations between culture and psychology. My primary goal in simultaneously applying these perspectives to my observations about adolescent pregnancy is not to choose among them, but to construct a view of the adolescent pregnancy system that is more comprehensive than any perspective alone can provide.

In the remainder of this chapter, I first explain why more research on the well-studied topic of adolescent pregnancy is needed and then briefly review the theories that helped me to understand adolescent pregnancy in this rural, African American population.

WHY MORE RESEARCH ON ADOLESCENT PREGNANCY IS NEEDED

The Problem

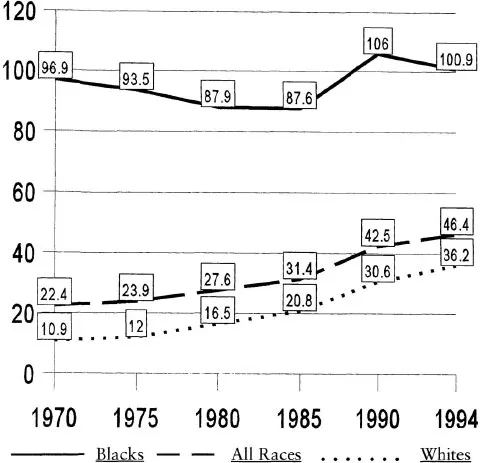

There are two primary reasons why adolescent pregnancy is increasingly viewed as a problem in our society. One is illustrated in Figure 1-1, which shows that birth rates to unmarried teenagers of all races combined have steadily increased since at least 1970 (Ventura, Martin, Mathews, & Clarke, 1996). Closer inspection of the figure shows that these increases are largely due to increases in rates for Whites.2 Rates for African Americans remained more or less stable between 1970 and 1994, with the 1994 rate only slightly higher than the 1970 rate. Whereas in 1970, birth rates to unmarried African American teenagers were almost 10 times as high as for Whites, the difference had narrowed by 1994 to only three times the rate for Whites.3 In other words, unmarried White teenagers have been increasingly likely since 1970 to give birth to a child, whereas the trend for African Americans has undulated within a fairly narrow range with the overall slope remaining flat. The increasing visibility of adolescent pregnancy as a social problem, then, must partly be attributed to overall trends in the White population.

Figure 1-1. Birth Rates to Unmarried Teens

Note. Data were taken from Ventura et al. (1995, 1996). These rates reflect the numbers of live births per 1,000 individuals in an Age x Race subgroup. Preliminary data for 1995 from the National Center for Health Statistics indicate that the birth rate for African American unmarried teenagers has dropped again to 95.5 births per 1,000 women from 100.9 in 1994 (Rosenberg et al., 1996). This continues a downward trend that has been in effect since 1991.

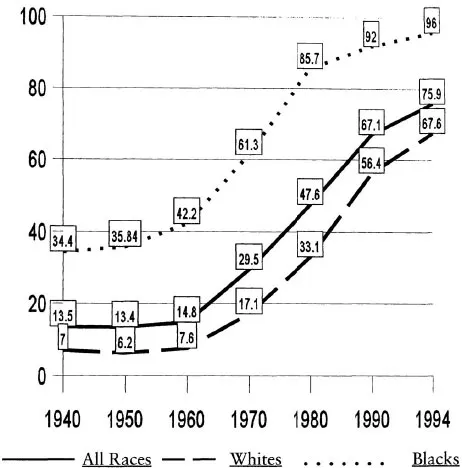

The second reason why adolescent pregnancy is increasingly viewed as a problem in our society can be inferred from Figure 1-2. Since 1940, the context for teenage pregnancies in both the Black and White populations has changed dramatically. Whereas in 1940, two-thirds of Black teenagers and 93% of White teenagers becoming pregnant did so in the context of marriage, in 1994 nearly all (96%) Black teenagers and 68% of White teenagers becoming pregnant were not married (Ventura et al., 1995, 1996). This change in the mating habits of teenagers of both races has been accompanied by increases in a host of other social problems that disproportionately plague families living in poverty, and especially poor African American families who are the continuing targets of racial discrimination. These problems include joblessness, drug usage, single parent households, welfare dependency, sexually transmitted diseases, failure to complete a high school education, and poor health for mothers and infants. Together with the increasing availability of contraceptives and the skyrocketing costs of entitlement programs for teenage girls who have no other source of support (Ladner, 1987), these social problems have transformed what once was viewed benignly as merely a cultural variant on mating, childrearing, and childbearing practices in the Black population into what is now viewed as a major social problem in urgent need of correction (Nathanson, 1991).

Figure 1-2. Percentages of Out-of-Wedlock Births to Teens

Note. Data were taken from Ventura et al. (1995, 1996). These rates reflect the numbers of live births per 1,000 individuals in an Age x Race subgroup.

In the past 20 years, much time, effort, and money have been expended trying to understand the adolescent pregnancy phenomenon and to reduce the incidence of such pregnancies among African Americans and other ethnic groups. As researchers now acknowledge (e.g., Dryfoos, 1990; Musick, 1993; Polit, 1986, 1989; Polit & White, 1988; Ward, 1991), the results of these massive efforts have been disappointing. On the one hand, scholars have yet to get much beyond surface explanations and intuition regarding why so many African American girls become pregnant as unwed adolescents. On the other hand, there is as yet little evidence that the recent declines in unmarried African American teen birth rates since 1991 represent anything more than the next segment of a basically flat trend line that has been moving within a narrow range since the 1970s or that this downward trend will be any more permanent or sustainable than the earlier decline seen in the period between 1970 and 1985. Indeed, as I discuss in the last chapter of this book, there are more reasons than not to predict increases rather than decreases in African American unmarried teen birth rates in future years.

Trends in Research and Intervention

Rather than focusing on problems of prevention, subsequent pregnancies, and the sociopsychological roots of adolescent pregnancy, intervention programs have focused primarily on adolescent girls who are already raising babies and on “feel good” support services that appeal to politicians under pressure to do something about the social ills of the inner city (Ward, 1991). Model and demonstration programs have taken as their mission the goal of linking adolescent mothers with existing educational, social, and health services, including “counseling, daycare, G.E.D. preparation, job training, parenting skills, nutrition supplements, referrals within bureaucracies and tickets to zoos, movies, or other public entertainments” (Ward, 1991, p. 7). Although these programs have improved the quality of life for adolescent girls and their babies, they have not substantially decreased unwed pregnancy rates.

In similar fashion, research has tended to focus more on the consequences of adolescent pregnancy for girls and their children than on precursors (cf. recent reviews by Brooks-Gunn & Chase-Landale, 1991; Brooks-Gunn St Furstenberg, 1986; Osofsky, Hann, & Peebles, 1993). The presumption that adolescent mothers beget adolescent mothers has led to the assumption that consequences of adolescent pregnancy in one generation of women are antecedents for the next. Both the presumption and the assumption, however, have been challenged by findings that adolescent mothers do not necessarily beget adolescent mothers (Furstenberg, Brooks-Gunn & Morgan, 1987; Furstenberg, Levine & Brooks-Gunn, 1990) and that adolescent pregnancies per se do not necessarily put lower income African American girls or their offspring at risk for long-term socioeconomic disadvantage (Geronimus & Korenman, 1991).

A second trend has been the reluctance to acknowledge the multifaceted and complex nature of the adolescent pregnancy phenomenon. Researchers and program planners alike have tended to focus on isolated correlates of adolescent pregnancy, such as poverty, low self-esteem, depression, undereducation, ignorance or inaccessibility of contraceptives, lack of parental guidance, or lack of role models without delving into the more perplexing problems of how and where these variables fit into an overall contextual framework or exactly how these ...